The Road to Equality After the War: AAPIs in the Civil War

On the road to civil rights for Asians and Pacific Islanders in the United States, the challenges faced connect to the Civil War and the promise of equality that was not easily granted to future generations.

This blog is a continuation of Those Who Served, a blog written in celebration of AANHPI Heritage Month and Civil War history. All information can be sourced from Asians and Pacific Islanders and the Civil War, a well-researched text on the subject edited by Carol A. Shively. We encourage readers to explore more from the experts who contributed invaluable research with the goal of making this largely unknown history visible.

The story of Asian Americans in the Civil War cannot be shared without the story of civil rights for Asian Americans. These events of exclusion and discrimination resulted in the wake of the Chinese Exclusion Act, which came right after the Civil War, denying AAPIs rights to citizenship. In many cases, full participation in education and democracy were threatened.

In these events of seeking justice and equality, Asians and Pacific Islanders looked to the 14th and 15th Amendments: the laws of the land that were made possible in the wake of the Civil War. These are some stories of AAPIs combating injustice, some successfully and some unsuccessfully, that can be connected to the Civil War:

The Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882

The first immigration law to probit immigration on basis of race or national origin, banning all immigration from China. Under Exclusion, processing of citizenship essentially meant denial. The law’s processing was lengthy, and immigration inspection stations became detention centers in which those seeking entry were commonly locked in for days, weeks and months. Sometimes, even American-born Asians would wind up being deported instead of allowed to land if they were unable to provide acceptable documentation.

Tape v. Hurley (1885)

Just two years after the Exclusion Act, Mamie Tape, an 8-year-old Chinese American girl and a U.S. citizen born to two Chinese immigrants, was denied entry to a California Spring Valley public school in 1884. When she and her parents challenged this exclusion, they cited the equal protection clause of the 14th Amendment that granted citizenship to formerly enslaved African Americans. “To deny a child, born of Chinese parents in this State, entrance to the public schools,” the court reasoned, is “a violation of the law of the state and the Constitution of the United States.”1

Though the Tapes initially succeeded, California would go on to pass a law calling for segregated schools, arguing that would satisfy the need for “equal protection.” Despite mother Mary Tape’s letter to the board of education that her demand for equality was “more American” than the “race prejudice” of school segregation, this would not be overturned until 1954. This was an example of students of color being considered “separate but equal,” even before Plessy v. Ferguson.

United States v. Wong Kim Ark (1895)

In this case, Wong Kim Ark, an American citizen by birth, was refused entry into the United States. This was on the grounds that because he was born to “aliens ineligible to citizenship,” 2 he was not a citizen, subject to the Chinese Exclusion Act and the 1790 Naturalization Act. U.S. citizenship was a basic right denied all Asian immigrants by the Naturalization Act, which restricted naturalization to “free white persons.”

He appealed to the U.S. Supreme Court in 1898, and his citizenship was upheld together with “all persons” 3 born in the U.S. This is a crucial example of how the 14th Amendment could protect such rights through its provision of equality.

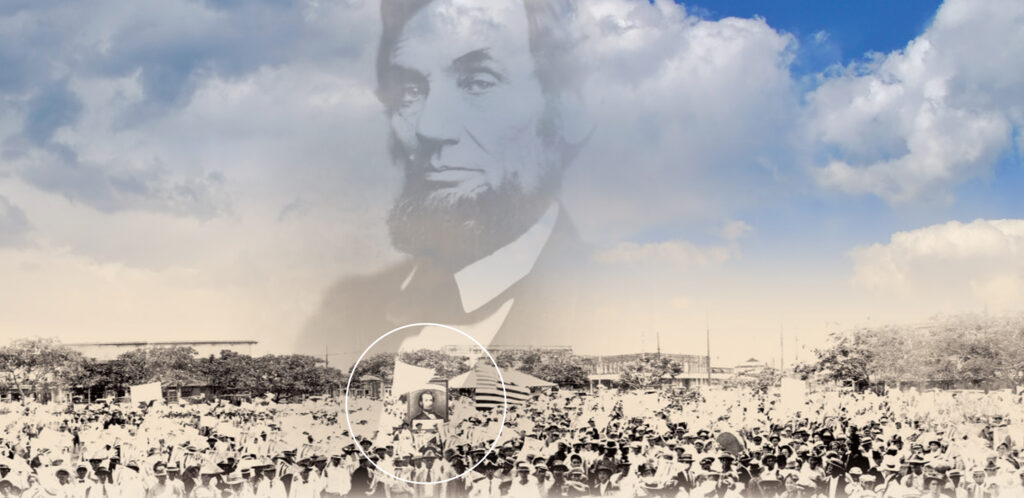

Sugar Plantation Strikes on Oahu

During the 1909 sugar plantation strike on the island of Oahu, Hawaii, Japanese strikers opposed racial and wage inequalities. This was one of many farmers’ workers strikes of this era, but we highlight this one as these workers invoked the 15th Amendment in their call for equality: “Is it not a matter of simple justice, and moral duty to give [the] same wages and same treatment to laborers of equal efficiency, irrespective of race, color, creed, nationality, or previous condition of servitude?” 3

The 15th Amendment states: “The right of citizens of the United States to vote shall not be denied or abridged by the United States or by any State on account of race, color, or previous condition of servitude.” While this strike was unrelated to voting, the inspiration from the language of equality – of “race, color, or previous condition of servitude” – is clearly drawn.

We also see the Civil War and Lincoln’s effect on the 1920 sugar strike, 11 years later. Filipino and Japanese men, women and children marched in downtown Honolulu, carrying portraits of President Abraham Lincoln, who was a symbol of liberation.

Gong Lum v. Rice (1927)

In another education case, in 1926, the nine-year-old Martha Lum tried to enroll in a white school in Bolivar County, Mississippi – but was not allowed, and informed by the superintendent that she was not white and had to enroll in the colored school. Gong Lum, Martha’s father, decided to fight for his daughter’s education, as he recognized that the white school had more advantages than the colored school.

In this case, the U.S. Supreme Court decided unanimously against Lum. Chief Justice William Howard Taft wrote racial segregation fell within the powers of the state in that, since Plessy, separate facilities and treatment fulfilled the equal protection clause of the 14th Amendment.

Looking Towards the Future

Throughout the 1940s and 1950s, a series of immigration laws overturned Exclusion and afforded the right to naturalize. By 1954, Asians and African Americans overturned the doctrine of “separate but equal” established by Plessy through Brown v. Board of Education. The Civil Rights Act of 1966 officially affirmed the end of institutional racial segregation and legal inequality. The fight for representation, visibility, power and equality doesn’t stop, but we celebrate the history of attaining civil rights that were fought and that continue to get their due in history today.

Citations:

- Okihiro, Gary Y. “From Civil War to Civil Rights.” Asians and PI and the Civil War, edited by Carol Shively, National Park Service, Washington, District of Columbia, 2014, p. 212, Accessed 15 May 2024.

- Okihiro, Gary Y. “From Civil War to Civil Rights.” Asians and PI and the Civil War, edited by Carol Shively, National Park Service, Washington, District of Columbia, 2014, pp. 215, Accessed 15 May 2024.

- The House Joint Resolution Proposing the 14th Amendment to the Constitution, June 16, 1866; Enrolled Acts and Resolutions of Congress, 1789-1999; General Records of the United States Government; Record Group 11; National Archives.

- Okihiro, Gary Y. “From Civil War to Civil Rights.” Asians and PI and the Civil War, edited by Carol Shively, National Park Service, Washington, District of Columbia, 2014, pp. 216, Accessed 15 May 2024.

- The House Joint Resolution Proposing the 15th Amendment to the Constitution, December 7, 1868; Enrolled Acts and Resolutions of Congress, 1789-1999; General Records of the United States Government; Record Group 11; National Archives.

- Okihiro, Gary Y. “From Civil War to Civil Rights.” Asians and PI and the Civil War, edited by Carol Shively, National Park Service, Washington, District of Columbia, 2014, pp. 210–227, Accessed 15 May 2024.

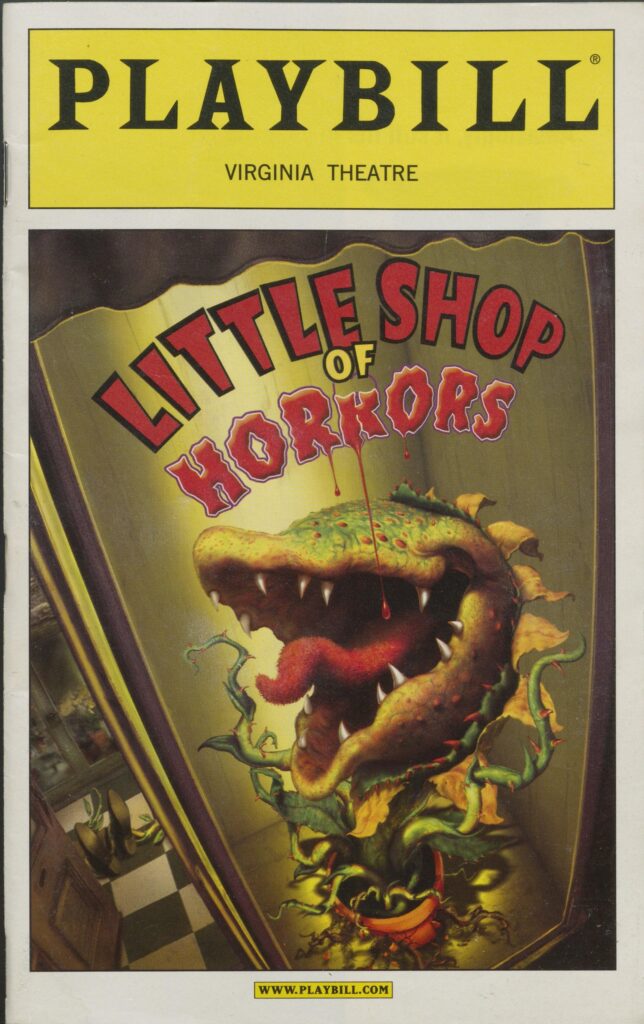

Suddenly Lincoln

Learn what Little Shop of Horrors can teach us about Abraham Lincoln.

We have all felt like Seymour Krelborn in Little Shop of Horrors at some point. The usually downtrodden Seymour has discovered a strange and interesting new plant after a solar eclipse. After his discovery seems to turn his fortunes around, this plant—which he names Audrey II in honor of his secret crush—begins to wilt and die. What follows is a classic musical number called “Grow For Me.” Just when it appears that Seymour’s life would change for the better, he is left begging this little sprout of hope to continue blessing him:

I’ve given you sunshine

I’ve given you dirt

You’ve given me nothin’

But heartache and hurt!

I’m beggin’ you sweetly

I’m down on my knees.

Oh, please –

Grow for me!

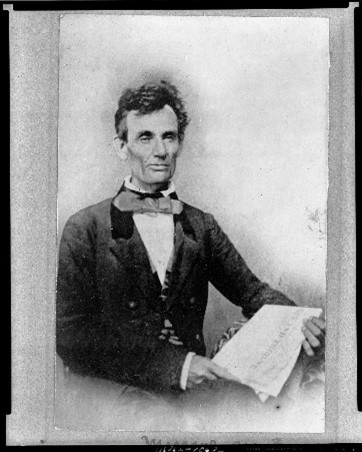

Before Abraham Lincoln—or anyone—knew this Illinois lawyer would be President of the United States, he ran two unsuccessful campaigns for the United States Senate in 1855 and 1858. As he lost both elections, the career of his longtime rival in Illinois state politics, Stephen Douglas, soared to newer heights in Congress. Douglas’s popularity and power was at its height in this period; politicos called him “the Little Giant” and people even predicted his ascendence to the White House.

As Lincoln’s prospects seem to go nowhere compared to Douglas, he wrote a private note to himself in 1856 that strikes a similar note as Seymour in “Grow For Me”:

“With me, the race of ambition has been a failure—a flat failure; with him [Stephen Douglas] it has been one of splendid success. His name fills the nation; and is not unknown, even, in foreign lands.”

Lincoln had given his political career sunshine, dirt and more, but it seemed in this moment that he would be doomed to always be second best, little more than a footnote compared to the perennial success of his world-renowned rival. It is a little heartbreaking to hear Lincoln call himself “a flat failure.” If only he knew!

Looking at the full scope of Lincoln’s life, however, this negative self-talk is not entirely surprising. Lincoln suffered with bouts of depression throughout his life. As a young man making his way in the world, Lincoln’s friends genuinely worried at times about his mental state. In a letter to a close friend in 1842, Lincoln even described his personal experiences with how “exposure to bad weather . . . [in] my experience clearly proves to be very severe on defective nerves.”1 His mother died when he was very young. He had a tumultuous relationship with his father. He lost two children to illness. Of course, he also navigated the country through the most challenging period in its history. Along the way, he led hundreds of thousands of men to sacrifice their lives to establish “a new birth of freedom,” a burden which Lincoln felt to his core.

This is not necessarily the Lincoln that we have grown up with. The face on the penny, the marble colossus and even the frontier tough rail-splitter are more familiar images. All are important national symbols, but there is something powerful in a human Lincoln, one that grappled with demons all too common in our society. Focusing too much on the mythic aspects of historical figures’ lives can create an unhealthy relationship between ourselves and our past. Specifically, hero worship can make us feel like we don’t measure up. How could we, when we build statues for them, whereas we are just . . . us, toiling away, hoping our own ambitions will grow like Seymour’s plant in Mushnik’s Skid Row Florists.

To aspire and live with purpose is to be human. Studies even show that living with a sense of purpose promotes good mental and physical health.2 But examining the fullness of Lincoln’s—or anyone else’s—experience teaches us to not let our ambitions get the best of us and to let disappointment pass. That examination also teaches us to take the time to study ourselves, to “live thoughtful and reflective lives” in the words of Lincoln scholar Ronald C. White.2

In the end, both Seymour and Lincoln experienced their own shares of success. Seymour finds romance and fame in Little Shop of Horrors, while Lincoln would go on to find a sense of purpose that has made him a legendary figure around the world. Even as he mourned himself as a “flat failure,” Lincoln also found comfort in dedicating that disappointment to something higher:

“I affect no contempt for the high eminence he [Douglas] has reached. So reached, that the oppressed of my species, might have shared with him in the elevation, I would rather stand on that eminence, than wear the richest crown that ever pressed a monarch’s brow.”

Finding success by elevating both ourselves and those around us is a healthy way to approach our ambitions. It is certainly healthier than feeding vampiric plants from outer space, and we see how Seymour’s selfish mindset – unlike Lincoln – has consequences. Come see Little Shop of Horrors at Ford’s Theatre and find out why!

Citations:

- Abraham Lincoln to Joshua Speed, January 1842, qtd. in Abraham Lincoln: Selected Speeches and Writings (New York: Library of America Paperback Classics, 1992), 30.

- Rosean Bishop, Ph.D., “Does purpose play a positive role in mental health?,” Mayo Clinic Health System, March 23, 2023. https://www.mayoclinichealthsystem.org/hometown-health/speaking-of-health/purpose-and-mental-health. Accessed March 14, 2024.

- Ronald C. White, Lincoln in Private: What His Personal Reflections Tell Us About Our Greatest President (New York: Random House, 2021), 163.

Little Shop of Horrors runs through May 18 at Ford’s Theatre. Get tickets here.

Blake Lindsey is the former Museum Interpretive Resources Specialist at Ford’s Theatre.

Little Shop, Big History

Explore the history of Little Shop from book to movie to musical, and how it impacted the American musical theatre canon, in this month’s blog post. This includes a look into the Howard Ashman Papers at the Library of Congress, which features original documents on his collaborations with Alan Menken.

“There were a lot of musicals and cabaret pieces in the late 70s and early 80s that were playing with the interface of apocalyptic, end-of-the-world, tacky horror movies and pop music. But Howard’s insistence that we remain truly heartfelt and knowing, yet not getting into self- mockery, was the key to what made us different.” –Alan Menken, Playbill

Book to Movie to Musical: A Brief History

Little Shop of Horrors’ origins date back to 1894, with English writer H.G. Wells’s curious short story The Flowering of the Strange Orchid, about a man-eating carnivorous plant. In 1932, John Collier wrote a dark comedy version called Green Thoughts, and in 1956, sci-fi writer Arthur C. Clarke wrote his take on the story with The Reluctant Orchid, which made the plant’s ominous intentions clear.

Both stories inspired original screenwriter Charles B. Griffith, who incorporated farce and humor into the horror story, with American actor/filmmaker/producer/film distributor Roger Corman’s B-movie film The Passionate People Eater. Corman shot the film in two days and one night, on the set of another B-movie, Bucket of Blood. It entered public domain as The Little Shop of Horrors.

In 1982, Howard Ashman and Alan Menken adapted the film into what we know now as the beloved musical Little Shop of Horrors – which began Off-Off-Broadway at the WPA Theatre and transferred to the Orpheum Theatre Off-Broadway. It was adapted back into a movie directed by Frank Oz in 1986, with Rick Moranis and Ellen Greene, and a “happier” ending than the musical after test audiences found the original musical’s ending too sad for a movie.

Major productions of Little Shop include the 2003 Broadway production – over 20 years after its Off–Broadway debut and considered a “revival” at the Tony Awards despite being the Broadway debut – and the current Off–Broadway revival that has been running in New York since 2019. Recently, it was announced that Roger Corman, Joe Dante and Brad Krevoy are working on a reboot series titled Little Shop of Halloween Horrors.

Little Shop has been a favorite of regional theatres for decades. In recent times, a 2019 production at the Pasadena Playhouse (where Ford’s Theatre Senior Artistic Advisor Sheldon Epps formerly served as Artistic Director, prior to this production) starred George Salazar as Seymour, MJ Rodriguez as Audrey and Amber Riley as Audrey II. On the Ford’s stage, audiences last saw this musical in 2010. Now, with Kevin S. McAllister’s take on the show here at Ford’s, we see representation at its finest in a production with inspired casting, without saying it “in capital letters.”

Little Shop of Horrors in the American Musical Theatre Canon

Little Shop is one of a kind, as the one of the first “horror comedies” in musical theatre, setting the standard to combine the macabre with humor when musicalizing horror stories. Perhaps the only other musical with a similar goal that preceded it was Rocky Horror Show, which has a similar spirit. And it still stands as one of the only “horror comedy rock musicals.”

It rocked the world in terms of making Off-Broadway a viable commercial venture, originating from the WPA Theatre Off-Off-Broadway, where Ashman was the Artistic Director, and the Orpheum Theatre Off-Broadway. At the time of its original Off-Broadway run, it broke box office records as the highest grossing Off-Broadway musical.

Its musical style is worthy of note: Howard Ashman and Alan Menken originally said that it is meant to be “the dark side of Grease, using doo-wop, R&B and rock-and-roll as the main vocabulary for the score.” Yet the score still has classic musical theatre moments, like the patter of “Closed for Renovation” and “Call Back in the Morning,” and the sweet “I Want” song of “Somewhere That’s Green.”

Little Shop also came about around the time that Ashman and Menken’s Disney careers were in development. After the 1986 Little Shop of Horrors film, they were tapped to contribute music to Oliver and Company, followed by The Little Mermaid – which sparked the Disney Renaissance that popularized musical movies for audiences of all ages, for generations to come. This show and its creators have made an indelible impact on contemporary musical theatre and what it can sound like – from musicals that use rock, R&B and doo-wop styles, to the musicals that take inspiration from the Disney tradition of knowing exactly how to draw out emotion through song.

Did You Know? Trivia About Little Shop and Its Creators

- During the original 1982 production, Stephen Sondheim sent a note of congratulations to Howard Ashman that is a rare gem of the Library of Congress, applauding Ashman for his “style, wit and delight. The more I think about it, the more I like it.”

- A note on “I Want” songs: Ashman and Menken’s “Somewhere That’s Green” and “Part of Your World” from The Little Mermaid have a lot of similarities. They have recitative at the top, have similar structure of having choruses and one bridge, and end very similarly (“out of the sea” / “far from Skid Row”).

- Yes, the dates in the song “Little Shop of Horrors” changed: In the original 1982 script of the musical all the way up to the 2003 Broadway version, the lyric is “The 21st Day of September.” In the movie only, right from the 1984 Frank Oz draft of the screenplay, the lyric is “The 23rd Day of December.”

- Did you know that Alan Menken composed music for a television documentary called Lincoln in 1992, celebrating our nation’s 16th president with appearances from a stacked cast that included James Earl Jones, Jason Robards, Glenn Close, Arnold Schwarzenegger and Oprah Winfrey? Explore the music of that documentary here.

Little Shop of Horrors runs through May 18 at Ford’s Theatre. Get tickets here.

Explore the Howard Ashman Collection and refer to the Finding Aid here.

For a deeper dive into the movie’s history, check out our digital program, where Ford’s Theatre Director of Artistic Programming José Carrasquillo takes audiences through that timeline.

Civil Discourse: Communicating and Listening to Create a Compassionate Culture

A Ford’s Theatre National Oratory Fellow reflects on challenging yet caring conversations in her work as a fellow.

I vividly remember sitting in a classroom 14 years ago, a wide-eyed future educator, dreaming of the day when I would be the teacher. Students would be engaged in discussions about the latest book they read, analyzing every detail while forging connections, even racing home to share their favorite parts. Parents would be overjoyed that finally, their child had developed a love of reading because they saw themselves on the pages, felt themselves in the prose. Fast-forward to 2023, and that dream has come true, but still remains.

As a Ford’s Theatre National Oratory Fellow, I work with educators from across the nation to help students find and develop their voices as public speakers and writers. Part of that work includes teaching the concept of civil discourse, which is being able to articulate personal views while being a respectful listener of differing perspectives. With our students, we model how to communicate without being critical, listen without loathing and debate without denying.

To achieve these goals, I begin the year with students working in small groups to identify what discourse is and how it looks. Once learners create a general list of rules in their groups, we share out to create Classroom Rules for Civil Discourse that guide our interactions and discussions throughout the year. This year, our rules included being patient in conversations, listening to everyone’s entire argument and taking into consideration the speaker’s circumstances. By having this reference point and agreed upon boundaries for challenging conversations, students learn to hold each other, and themselves, accountable for their thoughts and ideas.

Brave spaces are ignited where conversations can be held and opinions can be shared, especially in the face of disagreements. Can this be challenging? Absolutely. Yet it’s important and necessary work that even the adults in the room can benefit from being reminded of.

“Brave spaces are ignited where conversations can be held and opinions can be shared, especially in the face of disagreements.”

Often, an open discussion between two individuals who actively listen to one another, free from judgement, could alleviate the tension in elevated situations. Opening the avenue for conversation and being willing to listen is the first step in working together and understanding differing perspectives. As individuals, we can begin by informing ourselves on current events and issues displayed in popular young adult literature and researching authors themselves to engage in informed discussion. By doing so, we practice what we teach to our youngest learners, which is how to express their thoughts in a polite manner while holding challenging conversations, and modeling what it means to create a culture of compassion and gain knowledge and understanding outside of our own views.

Since joining the National Oratory Fellowship program, I have learned how to create space effectively and intentionally for civil discourse in my classroom, regardless of the topic. My students put in the challenging work to build their viewpoints through credible sources to establish ethos, share their views in an appropriate manner utilizing podium points and acknowledge that the opinions and values of others hold equal value to their own. Through civil discourse, we can better understand one another and learn more about ourselves along the way.

Resources for Teaching Civil Discourse in the Classroom:

- Warm and Cool Feedback: Video, Lesson Plan

- Rhetorical Triangle: Video, Lesson Plan

- Podium Points: Video, Lesson Plan

- National Council for the Social Studies

- Bill of Rights Institute

Applications are open now through March 29, 2024 for the 2024-2025 Ford’s Theatre National Oratory Fellowship program. Apply here.

Lauren Baxter is a 7th grade English-Language Arts teacher at Cocalico Middle School in Denver, Pennsylvania.

Explore the World of Carnivorous Plants with Little Shop of Horrors and the U.S. Botanic Garden

Learn about the science behind how carnivorous plants work, and how much it’s incorporated into the story of Little Shop of Horrors!

We stopped by the U.S. Botanic Garden with Derrick D. Truby, Jr. and Chani Wereley, our stars of Little Shop of Horrors, to learn about the science behind carnivorous plants. How much does the show take inspiration from the real world of carnivorous plants?

Audrey II vs. Venus Flytrap

Audrey II is one of a kind, but did you know that she is based off a real Venus flytrap?

- In Little Shop of Horrors, Audrey II has a mouth. Venus flytraps do look like they have lots of mouths in real life!

- While Audrey II is a human-devouring carnivorous plant, real Venus flytraps can’t actually hurt people! In particular: The vicious looking hairs on the outside of them are actually very soft.

- Audrey II and Venus flytraps both eat prey. In a real Venus flytrap, the leaves are composed of two sides, each with three trigger hairs. Each of the hairs need to be triggered in 15 seconds in order for the trap to snap shut. Afterwards, the hairs need to be continually triggered for quite a while in order for the leaves to seal shut and start releasing digestive enzymes. The prey (usually insects, not normally a finger) will be completely digestive except for, sometimes, the exoskeleton of the insect.

Your Guide to Carnivorous Plants

We explored the various other kinds of carnivorous plants that inspired Audrey II beyond Venus flytraps. Explore the world of carnivorous plants:

- Venus flytraps (Dionaea muscipula): They are native to the United States and grow between North and South Carolina.

- Cape sundew (Drosera capensis): From South Africa, these plants have bright leaves and sticky hairs, which attract insects to the leaves. The leaves will wrap around the insects, which are digested on the leaves.

- Australian pitcher plant (Cephalotus follicularis): These look a lot like Audrey II, because of their little, tiny teeth inside of the leaves!

- Mexican butterworts (Pinguicula spp.): These carnivorous succulents use their sticky leaves to catch small insects, who get digested on the leaves. They have little flowers that get pollinated by hummingbirds.

Digesting Human Flesh

In Little Shop of Horrors, Audrey II digests human flesh. And in real life, carnivorous plants can actually digest flesh! Let’s find out how:

Most carnivorous plants eat insects, but there are known instances of being able to capture and digest small animals like mice, rats and even frogs.

North American pitcher plants called sarracenia have beautiful colors and sweet-smelling leaves that attract insects down into their leaves. They have downward-pointing hairs and waxy surfaces that don’t allow the insects to escape. When we cut them open, we see they are filled with digesting insects.

(It’s not the most pleasant smell. Chani can attest.)

Grow For Me!

Venus flytraps are commonly available carnivorous plants, and they’re extremely rewarding to grow. Singing to them might be fun, but here are three tips that will help you to grow your Venus flytraps:

- Unlike what the song states, giving them plant food is actually detrimental to the health of a Venus flytrap. They’re adaptive to environments with very little nutrients, so they’re not used to getting plant food.

- They love water! Make sure your Venus flytrap is always sitting in a tray of reverse osmosis, rain or distilled water.

- They love sun! If you can find a spot for them outdoors where they can get full sun and can catch their own food, that would be best. But if you can’t, a spot on a sunny windowsill in your apartment or home or under grill lights would be very helpful.

Ready to see our Audrey II in action? Come see Little Shop of Horrors at Ford’s Theatre, running March 15-May 18, 2024. Get tickets here.

Visit the U.S. Botanic Garden! Thank you to Devin Dotson and Zack Leibovitch for their contributions to these educational videos. Learn more and get tickets here.

A Tale of Two Symbols: Lincoln and the U.S. Capitol Dome

December 2023 will mark the 160th anniversary of the statue of Freedom topping the U.S. Capitol dome. All these years later, both President Abraham Lincoln and the Capitol dome’s legacies remain connected—and questioned.

It was December 2, 1863. A large crowd stood on the U.S. Capitol’s East Plaza, heads tilted back as they looked skyward, 288 feet above them. Even amid the Civil War and frigid temperatures, hopes ran high as the last piece of a massive new bronze statue, Freedom, was deposited on top of the U.S. Capitol’s dome.

As the final piece swung into position, the raising of a Union flag signaled—success!

The crowds cheered, and cannons positioned for miles around Washington thundered a deafening salute. “Let us indulge the hope,” wrote the National Intelligencer, “that our posterity to the end of time may look upon it with the same admiration.”1

After eight years of construction during an unprecedented national crisis, the Capitol’s dome, a symbol of Union and republican government, was crowned with a monumental statue personifying freedom. Although President Abraham Lincoln did not attend the ceremony—he had a mild case of smallpox—his symbolic presence at the event was undeniable.

Just weeks previously, Lincoln spoke about a “new birth of freedom” during his famous Gettysburg Address. The statue carried his imprint; the engineer who installed it stamped “A LINCOLN PRESIDENT” on its feathered headdress, where it remains today.

The relationship between Lincoln, the U.S. Capitol dome and freedom is a rare example of historical meaning writing itself. Tracking the evolution of the dome and the rising tide of emancipation during Lincoln’s presidency is a study of parallel growth. Their legacies are intertwined as enduring symbols of the United States and its ideals, and handy lenses to view Lincoln’s place in the history of real freedom for real people.

Which Union Would Go On?: Parallels in Construction

From the beginning of Lincoln’s administration, his destiny and the destiny of this unfinished monument seemed locked together in orbit around the gravity of events. Case in point: the physical and metaphorical progress of the dome’s construction.

Work temporarily stopped on the dome project when Confederate forces in Charleston, South Carolina, fired on Fort Sumter a month after Lincoln’s first inauguration. Pieces of white painted cast-iron laid inert around Capitol Square. Northern militias who rushed to defend the exposed Union capital city used them as barricades, expecting to defend the Capitol building from insurrection.

Once it was clear the city was at least temporarily safe from attack a few months later, work resumed. Lincoln noticed the important symbolism of the Capitol’s ongoing construction. He famously told a friend that: “If people see the Capitol going on, it is a sign that we intend the Union shall go on.”

But which Union would go on? Again, the Capitol dome reflected the times, showing the ambivalence of both Lincoln’s stance on the issue at this moment and the cruel ironies caught in the middle of war, politics and architecture.

The Building of Freedom: Parallels in Emancipation

Amid this artistic and historical contradiction, Congress passed the D.C. Compensated Emancipation Act in April 1862, freeing all enslaved people within the District of Columbia. Freedom came with a catch: enslavers were compensated for the loss of “their property.”

Although an unprecedented first step, questions remained. How would freedom come for millions of others through the South and border states like Maryland? And what would this freedom mean without legal guarantees to equal citizenship? The half-finished dome was a visual reminder of the awkward middle ground between freedom and justice the Compensated Emancipation Act represented: the promise of hope, without all the guarantees of equality.

Throughout 1862, Freedom’s construction and emancipation persisted. In October, Lincoln revealed the preliminary Emancipation Proclamation, signaling a steady but ambiguous path. By year’s end, the completed Freedom arrived at the Capitol grounds, where it waited to be placed on the dome.

Philip Reid, an enslaved man, was instrumental in the completion of Freedom. In 1863, the year the Emancipation Proclamation was issued, the New York Tribune asked: “Was there a prophecy in that moment when the slave became the artist, and with rare poetic justice, reconstructed the beautiful symbol of freedom in America?”2

Considering Freedom from April 14, 1865, to Today

On April 14, 1865, John Wilkes Booth shot Lincoln at Ford’s Theatre, a murderous attempt to prevent this reconstruction of freedom. Even in death, Lincoln cemented the dome’s importance. His body Lied in State underneath the dome and Freedom, as thousands mourned him.

Almost immediately, the country leveraged images of Lincoln, Freedom and the dome as shorthand for national reunification. But questions about the country’s future remained unanswered.

These symbols’ legacies remain unsettled today. “So did Lincoln even care about slaves?” a student asked me during their field trip to Ford’s Theatre, standing near a model of the unfinished Capitol dome.

It’s a fair question that historians continue to research and discuss—but one single blog post or field trip can’t answer it definitively. Lincoln’s words and actions are all that is left for us to assess his life and his legacy.

160 years after Freedom first stood triumphantly over the nation, the Capitol dome cannot speak for itself. It falls on us, the citizens of the country it represents, to define its meaning.

1 National Intelligencer, Dec. 2, 1863.

2 Correspondent of New York Tribune, Dec. 2, 1863, qtd. in George W. Williams, History of the Negro Race in America (New York: G.P. Putnam, 1885), 557.

Join Ford’s Theatre Education on March 4, 2024, for a virtual history talk looking deeper into the connections between Lincoln, the Capitol dome and their impact today.

Stay up to date on public programs with Ford’s Theatre Education for more discussions at the nexus of Lincoln’s history and impact today.

Blake Lindsey is the former Museum Interpretive Resources Specialist at Ford’s Theatre.

From Kids Camp to the Ford’s Theatre Stage: Meet 2023 A Christmas Carol Young Company Members

Get to know some of our young company!

A Christmas Carol is always a joyous occasion here at Ford’s Theatre. Our young company is just one reason! In this month’s blog, we take you behind the scenes to rehearsals with some of the brightest young stars to hit the Ford‘s Theatre stage.

This year, the Young Company experienced what Artistic Programming Manager and A Christmas Carol Associate Director Erika Scott and Company Manager Martita Slayden-Robinson called “Kids Camp” – a focused introduction to everything A Christmas Carol. During Kids Camp, they got a leg up on the dialects, choreography and staging together before rehearsals with the adults began.

“It was definitely different from a full rehearsal with adults,” said Riglee Bryson of Clifton, Virginia, who plays Belinda Cratchit. “It was fun and laid back. Now with the adults, it’s more professional, but I like that! …But Kids Camp was fun and a great way to start the season! I’m glad we did it.”

According to Taylor Esguerra of Sterling, Virginia, who plays Martha Cratchit, that the kids camp “was helpful and gave us a good introduction on how rehearsals might work.”

Nicolas Cabrera of Washington, D.C., who plays Turkey Boy, agreed. “I think it was fun and helped me at least feel prepared,” he said.

It was also the first chance to start getting to know their fellow young company members.

“Kids Camp was so much fun and something to look forward to before rehearsals started,” said Adrianna Weir of Stafford, Virginia, who plays Fan and Want. “Getting to meet the rest of the kids was the best part.”

“It was a great way to bond with the other kids in the cast!” said Ainsley Zauel, of Fairfax Station, Virginia, who plays Martha Cratchit. “It was so fun to practice our dialects and learn the dances together!”

Once rehearsals began, the young actors were assigned their teams, either Red or Green and immersed in a three-week process along with the adult company. During the rehearsal process, one team will quickly review a scene while the other watches, then move swiftly to switch teams so the other young cast has a chance to walk through the same sequence.

The kids and any newcomers to the cast are added in. Guided in the room with support from Erika, Associate Director Craig Horness and Director José Carrasquillo, it’s a joy to get to learn the ropes and watch the professional adults. Plus, the chance to simply have fun is a huge plus for the kids.

“It’s exciting that I get to be in one of the biggest shows in D.C. at one of the most unique places,” says Harrison Morford of Aldie, Virginia, who plays Tiny Tim. “It’s really fun working with the adult actors because they are so good and I am learning a lot. I also really like riding on the sleigh because I wasn’t able to do sled riding last year because it didn’t snow.”

One aspect of this rehearsal process’ patient yet challenging environment: the kids can honestly say “nope” when asked “Do you know where you’re going next?” and get the answers, while still having the empowerment to dance themselves and work hard.

“I have learned to be patient and true to my character, really becoming my character. Watching the adults in their character makes me want to be more my character,” Riglee said. “It really is an honor to perform at Ford’s and with these amazing actors and management. I can already tell they will be my friends and supporters forever!”

It’s also exciting to learn the traditions that come with A Christmas Carol. Some moments that multiple kids noted include the Cratchit scenes, learning how to use British accents and more. The Fezziwig dance is one highlight, where during rehearsals, Dance Captain and actor Justine “Icy” Moral helped break down the step sequences and kept the kids and adults on the same page.

“I like learning the Fezziwig dance (even though it’s complicated and tiring)!” said Kieran Tyan of Maryland, who plays Peter Cratchit. “I also like setting the Cratchit table, the town scenes and pulling the sled.”

William Morford of Aldie, Virginia, who plays Turkey Boy, Boy Scrooge and Ignorance, said he thought it’d be hard to remember the whole dance because it’s really long and tricky. “But the directors were really kind and good at splitting it up to teach it,” he said. “After practicing, I thought it was really fun and thrilling.”

A big joy of the young company is giving an outlet for a new generation of performers in D.C.: some who’ve performed professionally before, some who are making their debuts. It’s Kieran’s first year in any production, and he says he’s always loved to act. “I’m amazed that I got in and excited to learn more and bond with the other kid and adult actors,” he said.

The young company this year also has two sets of siblings: Elmer and Harlan Killebrew, and William and Harrison Morford. Harrison and Harlan both play Tiny Tim.

“I was really excited to make new friends and it was fun watching last year’s performance the first day of Kids Camp. I quickly became friends with Harlan, the other Tiny Tim,” Harrison said. “Harlan and I had a lot of time to get to know each other during the Kids Camp.”

For the Morfords, whose mimi Joyce Appleman has participated in the Ford’s Oratory program and was one of the teachers honored in this year’s Ford’s Annual Gala, it’s a family affair. “It’s neat we both get to do something at Ford’s,” William said.

As they near performances, the reality that performers from a young age get to be on the Ford’s stage sinks in. There is much excitement in being part of this annual D.C. tradition at our historic theatre.

“It is so exciting to be a part of a special show that is meaningful to audiences at Christmas time. I love being a part of people’s Christmas traditions and celebrations,” Ainsley said. “It is also amazing to be performing at a historic theater – it amazes me to think of all the history here! It is really special to be a small part of an amazing show that provides joy to others. I am so grateful for this opportunity!”

A Christmas Carol by Charles Dickens, adapted by Michael Wilson and directed by Michael Baron, runs November 17-December 31, 2023. Get tickets here.

Navigating History and Civics: Anatomy of a Walking Tour

Something Moving: A Meditation on Maynard is a powerful reminder of the lasting importance of public service. Inspired by Pearl Cleage’s work, Ford’s Theatre Education recently hosted a walking tour of Capitol Hill to share stories of service leadership in action during the Civil War.

Who doesn’t love a good, old-fashioned history walking tour? There is nothing quite like learning history by walking in the footsteps of people who used their will and ingenuity to change their community and the world.

Inspired by Ford’s Theatre’s upcoming world premiere of Pearl Cleage’s Something Moving: A Meditation on Maynard, Ford’s Theatre Education hosted a walking tour called Capitol Strides: From the Civil War to Maynard Jackson on September 16, 2023. With the help of Events DC and two great storytellers – licensed D.C. Tour Guide Rohulamin Quander and Ford’s Theatre Board of Trustees member Dr. Giani Clarkson – participants traveled back in time to reflect on civic action and leadership.

The tour came about from a simple idea: get out in the community, share the wonderful history around us and create excitement about Something Moving. This new groundbreaking play examines how Maynard Holbrook Jackson, Jr.’s 1973 election as Mayor of Atlanta inspired and unified his community by making its government accountable to all its citizens. In a rebuke to the horrid legacy of Jim Crow, Jackson paid attention to underserved citizens, and the play’s characters reflect on their own relationship to that work. But as the characters realize, and as our guides reminded us, Jackson did not do this work alone. He understood that he walked in the footsteps of citizen-activists who came before him.

Being Ford’s Theatre, we naturally looked to Washington, D.C.’s rich Civil War history to find those citizen-activists. It did not take long to identify stories of ordinary people taking extraordinary action to move their own communities towards “liberty and justice for all” in ways that inspired future generations, up to and including Maynard Jackson. On this day, we would move our bodies and our minds as we learned from their examples.

We started at the East Plaza of the Capitol. It was a fitting place to establish the historical context of the Civil War. Abraham Lincoln delivered both his inaugural addresses here. Amid the backdrop of an unfinished Capitol building, he spoke about the unfinished work of delivering on America’s lofty ideals. We reflected especially on a landmark rarely noticed by passersby: a simple bronze compass embedded within the East Plaza’s paving stones. It brought to our minds a question all good leaders must ask themselves: what guides our choices? Fame? Legacy? Service to others? Being in touch with our own moral compass is equally vital to citizenship as we evaluate candidates and consider policy within our communities. This metaphor was our lens as we dived into other history on the Hill.

Our next stop was the Jefferson Building of the Library of Congress. During the Civil War, this site was not the monumental center of knowledge and learning it is today. Instead, it was a series of multi-story brick buildings known as Duff Green’s Row that housed many thousands of newly freed refugees from slavery. It was in these buildings that Harriet Jacobs, a woman who had escaped slavery years before, tirelessly worked to both relieve suffering borne of dangerous overcrowding and define freedom for people to whom it had been denied. She helped them find paying work, established schools and wrote to sympathetic organizations in the North for material aid. Jacobs exemplified the power of selfless advocacy for others in need.

Just around the corner stood our next and last stop: the Rayburn House Office Building. Today, this space is a crucible for the democratic process itself, where members of Congress work with each other to write and discuss legislation. It is where “we, the people” have our voices heard. Jackson certainly knew the building well. In 2001, he testified here on the importance of respecting and protecting minority voting rights: “We often hear that the struggle for freedom and the civil rights movement are over,” he said, “[that] those two walking hand in hand are of another era. The struggle for freedom is twofold: 1) get free and 2) stay free. We are currently in the stay free phase of our existence.”[1]

Jackson’s words certainly resonated with history on this exact spot a century and a half before. During the Civil War, the current location of the Rayburn Building was the site of the Israel Bethel Colored Methodist Episcopal Church. This church was a focal point for African American activism at the time, and its pastor, Reverend Henry McNeal Turner, was a leading voice pushing President Lincoln and Congress to recognize African American service in the United States Army and Navy. Lincoln personally appointed Turner as the chaplain of the 1st United States Colored Troops. Other associates of Israel Bethel, such as Reverend Henry Highland Garnet, worked to have Lincoln and Congress to recognize Black voting rights.

Led by great storytellers, this history reminded our audience of the vital role of citizen leadership in creating change both locally and nationally. It was a lesson that Maynard Jackson understood well throughout his public career. Come experience Something Moving, and you will see the same mission unfold on the stage at Ford’s Theatre.

1 “Election Reform.” C-SPAN video, 3:12:41. February 27, 2001. https://www.c-span.org/video/?162821-1/election-reform.

Something Moving: A Meditation on Maynard by Pearl Cleage, directed by Seema Sueko, runs September 22 – October 15, 2023. Get tickets here.

“Everyone Called Him Maynard”: On Growing Up with Maynard Jackson, From Daughter Elizabeth Jackson Hodges

Elizabeth “Beth” Jackson Hodges sat down with Ford’s Theatre to chat about the man that everyone’s talking about in Something Moving: A Meditation on Maynard: her father, Maynard Holbrook Jackson, Jr.

FORD’S THEATRE: Who was Maynard Jackson?

ELIZABETH JACKSON HODGES: Maynard Jackson was an activist, a politician, an entrepreneur, a philanthropist. He was a great dad. He was a son of Morehouse College (a very proud Morehouse man), a proud Atlantan…That’s who Maynard Jackson was.

What was it like growing up as the first daughter of Atlanta, especially during the 70’s?

JACKSON HODGES: It was an adventure and fascinating time growing up in Atlanta because I was surrounded by so many wonderful people. I was a little insulated from bad things that were happening to Black people in other cities, and in other places around the world, because I was in Atlanta. I was surrounded by Black doctors, dentists, educators, business owners and policemen. Growing up in Atlanta was like growing up on your own safe island. As a pre-teen in the ’70s and into my teenage years, I was made aware of the Civil Rights Movement and what it did to break down the racial segregation barriers through my parents, family and my neighbors.

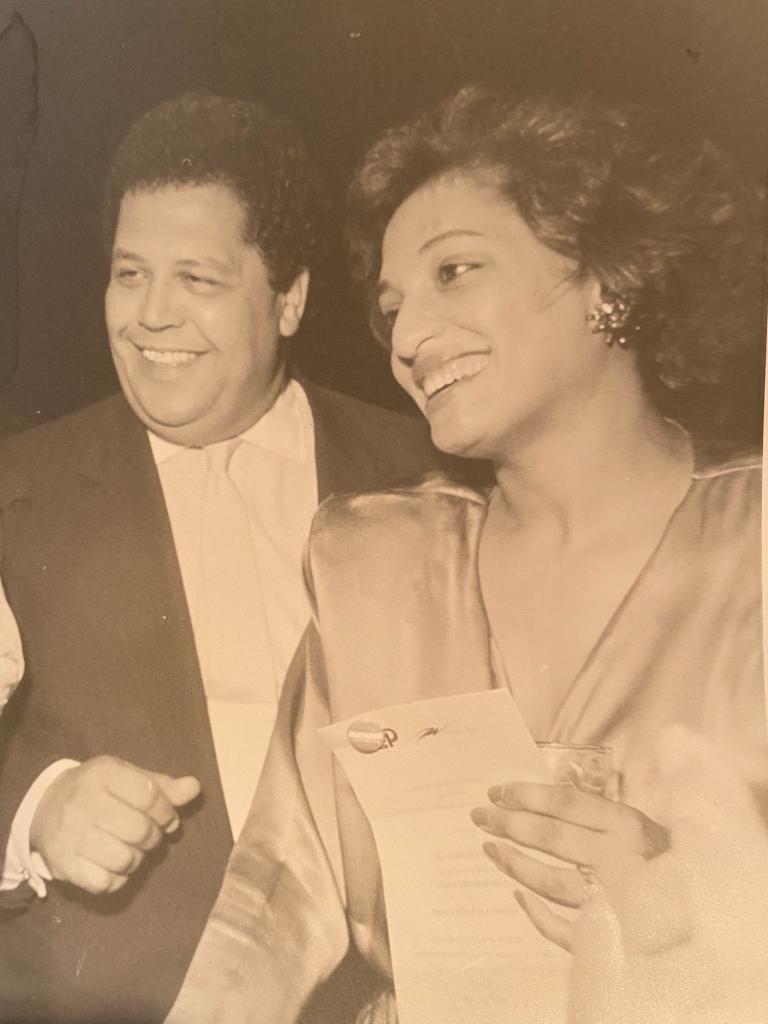

Where were you when Maynard won the historic 1973 election?

JACKSON HODGES: Campaign night: I remember when he won the office. I remember that my Mom, grandmother, family members and I went to the Hyatt Regency in Atlanta for the campaign night celebration. I was 12 years old, but I do remember the initial roaring celebration of the crowd when Dad proclaimed that he was the next mayor of Atlanta. But after that I was shuffled off the podium and taken to our hotel room, it was bedtime for me. I didn’t get to participate in a lot of the celebrating because I was young.

Going to sleep that night, did you know things were going to change? Were you able to recognize at all how monumental this would be for history?

JACKSON HODGES: Not at all. I was not aware at the time of the many way things would change for me or my family. I don’t think I was old enough to really understand the magnitude of the moment and the trajectory of history. The next election, as an older child…I was able to recognize it, embrace it, feel it.

How did you navigate moving from protest to power?

JACKSON HODGES: I participated in many political campaigns because of my dad. I volunteered on all his campaigns, and several local campaigns. I think that was my way, as a young person, to participate in the movement as much as I could.

What was the impact of your father’s political career on you personally?

JACKSON HODGES: The effects of being the daughter of a politician were full of interesting exposures to diverse people, places and spaces, and also a challenging way to grow up, finding my identity in the spotlight. Because of the death threats that my father received, I had full-time police executive protection from junior high through high school. I had Atlanta police detectives with me all the time. Which made life very interesting! Especially in high school when you’re sort of trying to have a social life and you always have an Atlanta police officer with you. So, I was sure that all the young men who approached me must have really liked me because they had to have the courage to approach me with a big guy with a gun standing next to me! We also had executive protection at our home, with officers sitting in marked patrol cars outside our house. However, we were allowed to have friends from our neighborhood visit. Our home became a hub of activity for family and friends. I think those personal limitations on my freedom to go places alone was the biggest impact. I’m still very close to those officers who cared for my Dad and our family. We have lunch and reminisce often; these gentlemen kept me safe – and even taught me how to drive. They were like big brothers to me, they were wonderful.

Your father opened the door for many Black entrepreneurs. He was an entrepreneur himself. Can you talk about the impact your father had in creating a pipeline for businesses and generational wealth in Atlanta?

JACKSON HODGES: My father worked very hard to break down the barriers of economic exclusion and to create a level playing field in city contract procurement, in corporate boardrooms and corporate suites in Atlanta for women and minority-owned businesses. In 1974, in his first term as mayor, 1% of Atlanta’s contracts were held by minority contractors and by the time he left five years later, 34-35% of Atlanta’s contracts were held by minority contractors. It was very important to him that minority and women businesses participated in building the new airport terminal and other major infrastructure projects. His philosophy was to widen the circle of opportunity and prosperity, to include everyone in the city.

What made your dad a special dad?

JACKSON HODGES: He had a wicked sense of humor. He had a beautiful singing voice – he could really sing! What made him special in my eyes was that he required me to think outside of myself. He always told me, you know, “It’s wonderful to write a check to an organization, and organizations and charities need money, but don’t forget to give of yourself and give your time.” This was something he always insisted and encouraged me to do. To this day, I still volunteer. Giving back to your community is something that he taught me that I cherish, and I try to do on a daily basis. I try to live my life that way.

Anything else?

JACKSON HODGES: He had a habit of getting up very early in the morning to ride around the city of Atlanta with his executive protection. He’d stop at the bus stops and talk to people going to work in the mornings – the nurses, the people who cleaned hotels, the students going to school, whoever was up standing at the bus stop at five, six o’clock, seven o’clock in the morning. He’d say “Hi, I’m Maynard Jackson.” He did out of love for his city and respect for the people of Atlanta. We always had a great time on these ventures because we’d get hot Krispy Kreme donuts before our ride. Then he’d see a patch of grass that needed to be cut, and he’d call his office, “Tell someone to cut the grass on the corner of whatever street.” He’d make unannounced drop-in visits to the various city departments early in the morning – Fire Department, Public Works, Transportation – and talk one-on-one to hear firsthand what was going on inside city government. He’d say, “Tell me about it,” whatever it is, just tell me about it. He was always open to listening to people.

Everyone called him by his first name. He campaigned that way, his slogan was “Maynard for Mayor,” so everyone just called him Maynard and that put him on first-name basis with all Atlantans. People would scream out, “Hey, Maynard, how are you today?” He would wave or return the greeting. There are so many heartfelt memories of my Dad – what he meant to me, my siblings, our family, the City of Atlanta and all the people he touched and inspired.

Elizabeth Jackson Hodges is a member of the Ford’s Theatre Board of Trustees and the Host Committee for Something Moving: A Meditation on Maynard. She is the eldest daughter of Maynard Jackson. She works as an entertainment agent and tour manager for artists.

Something Moving: A Meditation on Maynard by Pearl Cleage, directed by Seema Sueko, runs September 22 – October 15, 2023. Get tickets here.

The Other Members of the Choir: Meet the Citizens of Something Moving

As rehearsals for Something Moving: A Meditation on Maynard by Pearl Cleage get into full swing, our cast members share stories about their learnings and takeaways so far from this new work process. In telling a story about the power of individual action for the collective betterment of a community, we wanted to know: what moves them about Something Moving?

Want to know more? You’ll have to see Something Moving to dive deeper into citizens’ stories and meet everyone – because everyone’s stories make Something Moving move. Bear witness to what every single person has to say about their experience. Follow along as we highlight them on social media all month.

Billie Krishawn (Witness)

I’m not a citizen, but I’m the witness. What I’m learning is how much power comes with being a witness. We spend so much time figuring out how to take up space, but something about being a witness creates space for others to exist fully… to make change. Pearl herself is the perfect witness and throughout her lifetime her existence has allowed others to live more fully. As I continue to navigate the world, I hope to do more of that.

I love that the play has made me think about community deeper. Maynard hasn’t been here on this earth since 2003 and yet he’s somehow pushed me to take action to build the community around me. This play has done that for me and I’m so grateful for it.

It’s important the witness is included because we’ve all witnessed something, but what we choose to do with those stories determines how what we’ve lived through goes beyond just this current moment.

Kim Bey (Citizen 1)

Citizen 1 begins the journey among those who have become disillusioned with the political system and the present results of self-serving politicians and individuals who promote a “me culture” versus a “we culture.” But through her journey, Citizen 1 regains a connection to hope by seeing that community can be formed and can, indeed, fuel change in society.

Ms. Pearl Cleage has a way of embedding deep thought through the characters’ voices without moralizing. I embrace the challenge of telling this story highlighting the power of community through the life of wholly human, Mr. Maynard Jackson.

Constance Swain (Citizen 2)

I play Citizen 2. She is, as our script would say, an “upstart.” She isn’t afraid to challenge the system and definitely marches to the beat of her drum. Several times in our play, she stops the action to highlight a word or phrase. She invites the room to analyze the verbiage and often poses the question — are we really saying what we mean or are we just talking? Words are powerful – they can do good, and they can do harm. It’s our job to pick.

What I love most about this play is its celebration of community. In a world where everything is so individualized, it’s so refreshing, grounding even, to come together as these citizens to help tell the story of ordinary folks doing something extraordinary.

It’s important that my citizen’s story be represented in Maynard’s story because she represents the NOW. How Maynard’s impact and legacy has afforded her opportunities to push against the status quo, love who she loves and exercise her right to be young, gifted and Black.

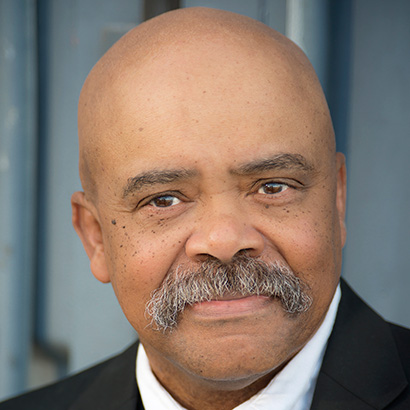

Doug Brown (Citizen 3)

Citizen 3 represents real people who are the seldom heard voices of his community. They are mostly from the low-income areas of Atlanta. They are veterans, blue-collar workers and mostly folks that appreciate and will utilize their newly acquired voting rights and did.

Working on this project has presented an opportunity to get input directly from the playwright herself, which has provided some unique and wonderful insights. I love that the play and casting include, in my opinion, one of this country’s most powerful assets, its diversity.

Shaquille Stewart (Citizen 4)

Working on new plays with the playwright in the room is so dope. You have the opportunity to ask questions about your character and the text that in other works you’d have to make inferences about. Citizen #4 is pretty close to how I saw myself a few years ago, curious, yet somehow apprehensive, newly acquainted with my own sense of blackness, spongelike and always watching.

As the character, each day I find new reasons to ask more questions about ATL [Atlanta] and the world around me, but as the person, I see how similar my own experience is. This is that type of work that makes you reach out to whoever is around you and learn about them, deeply appreciating their experience no matter how different or similar it may be to your own. I think having an open mind and open heart is key to this production. This becomes truer every day.

Susan Rome (Citizen 5)

As an actor, I love being part of the process of bringing new work into the world. I have long admired Pearl Cleage’s poetic artistry as a playwright. I was interested in this story in particular because of my family’s history (Jewish and Black) of being civically active in Baltimore and invested in bridging the gap between those populations, specifically. I also am deeply inspired by the ability of diverse groups to come together in a common goal to bring about deep change!

Tom Story (Citizen 6)

I love being a part of telling a story of our history that so many people don’t know. I am excited to share this story both with people who knew every detail of Maynard Jackson’s life, and people (like me) who knew almost nothing. Maybe even more than all of that – I love being in a room where a new community is being built. Mayor Jackson has brought us together. He is changing us as individuals, but he is DEMANDING that we work together to make our world better.

Alina Collins Maldonado (Citizen 7)

My citizen is someone I didn’t expect to see as a part of this story. Rarely had I heard a Latina voice from Atlanta history. Of course, this could have resulted from my ignorance before delving deeper into this play and Atlanta’s history. I am learning that this citizen can feel unheard, unseen and invisible, but they are essential catalysts of social change and integral community members. They love Atlanta.

I love that this play tells a story that I didn’t expect. I expected to only focus on telling Maynard Jackson’s story from his perspective and those close to him. Pearl Cleage has masterfully brought to life a moment that the people, not one person, fueled to create long-lasting social change in Atlanta. Maynard Jackson was a tremendous leader, and his success resulted from “people power.” Pearl Cleage humanizes politics and makes it personal by bringing to the forefront the people who were there and directly affected by the politics of the time. Telling history this way reminds us of our power, although we often feel powerless in politics. This play gave me hope.

Shubhangi Kuchibhotla (Citizen 8)

I love this play because it gives the audience a glance at what it means to capture American history wholly. We must remember all parts of American history, even the pain, and this play shows that it is a responsibility that belongs to all. To bear witness is a human duty and the play beautifully explores that concept.

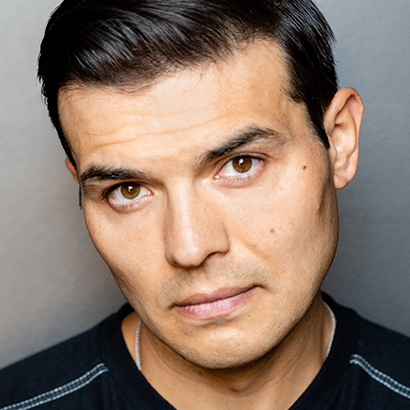

Derek Garza (Citizen 9)

I play Citizen 9, which is the Native character. New works are always exciting and full of discovery. You get to explore storytelling in new ways because this is a play that doesn’t have a history or set way of telling it.

Something Moving: A Meditation on Maynard by Pearl Cleage, directed by Seema Sueko, runs September 22 – October 15, 2023. Learn more about the cast and get tickets here.

Playwright Pearl Cleage In Her Own Words: A Conversation on Something Moving: A Meditation on Maynard

As we approach our highly anticipated world premiere of Something Moving: A Meditation on Maynard this fall, learn more about the world of Atlanta during Maynard Jackson’s time as mayor through Pearl Cleage’s eyes. This month on the Ford’s blog, we spoke with the acclaimed playwright, author, activist and Atlanta poet laureate about the impact of Mayor Maynard Jackson, the historical significance of this play and her writing process.

Something Moving: A Meditation on Maynard makes its world premiere at Ford’s Theatre this fall. It received a workshop earlier this year through The Ford’s Theatre Legacy Commissions and is written by Pearl Cleage (Blues for an Alabama Sky, Flyin’ West and more).

FORD’S THEATRE: How did the idea and major themes of Something Moving: A Meditation on Maynard come to you when you were first commissioned by The Ford’s Theatre Legacy Commissions?

PEARL CLEAGE (Playwright): I had been thinking about the upcoming 50th anniversary of Maynard Jackson’s election as Atlanta’s first African American mayor. It was a moment that changed the city in so many significant ways and had a major impact on the way the South, especially the Deep South, was perceived. I had worked for Maynard’s campaign and for almost three years as the Director of Communications when Jackson got to City Hall. It was a life-changing experience and gave me an up-close seat at a historic moment. When I was invited to be a part of the Ford’s Theatre Legacy Commissions, my first question was: does 50 years ago count as history because that’s the moment I want to write about? The Ford’s team assured me that 50 years was long enough to qualify.

I wanted to look at that moment as a time when many different communities in Atlanta came together in a way they never had before to elect this man we all felt was absolutely the right person to lead us through this transition period. I wanted to write a play that allowed me to create characters that would represent all the different constituencies that came together to elect Maynard our mayor. I wanted to ask myself (and my audience) what makes a great leader? I wanted to explore what we as citizens owe those leaders once we identify them. In these turbulent times when there is so much distrust of politicians and politics, I wanted to look back at a moment when we trusted the process and had great hopes invested in the outcome of every election. Maynard Jackson was elected less than 10 years after the Voting Rights Act. What did that kind of change mean for a city and its people?

FORD’S THEATRE: Audiences should be aware that though Maynard Jackson is the driving force of this story, he does not appear as an actual character. Can you talk about your decision to focus on the community and voices of Atlanta citizens, to paint a full picture of what it felt like to live in Atlanta during the era of Maynard’s public service?

CLEAGE: I didn’t have any interest in doing a biographical play about Maynard. I was more interested in the people of the city who invested their hopes in his election. I wanted to show the range of people who came together in a way they never had before, across lines of race and class and religion to support this man who seemed to embody our collective hopes and dreams. I hoped by allowing these fictional characters to tell their stories, I could give people an idea of not just what happened, but how it felt to be here, participating, making history with complete awareness of all that meant.

FORD’S THEATRE: How did you bring your own lived experiences as Director of Communications for Maynard into your writing process? What was your philosophy behind deciding which historical moments in Maynard’s life to include and which to leave for audiences to learn more on their own?

CLEAGE: I volunteered for Maynard Jackson’s 1973 campaign as a speechwriter. My first assignment was a speech he was making to Vietnam veterans. My husband and I wrote the speech together and submitted it to him. On the afternoon of the day he gave the speech, he pulled up in front of our little house in a big black Lincoln, climbed out and rang the front doorbell. We were a little intimidated, but when we opened it, he was effusive in his praise of our work. “Best speech I ever had written for me!” he said, and that was it. We couldn’t wait for our next assignment. It was years later when I heard another speechwriter say he had said exactly the same thing to her. We laughed about how like him that was.

In telling this story, I tried to give enough historical information so people who don’t know this part of our history would find a way into the narrative, but not so much that they would get overwhelmed by the details. My hope is that the moments that were so important to me as a citizen/volunteer will also resonate with other people who might not know all the names and dates and specific Atlanta history, but who could be swept along by the power of the story itself and by the impact of the man at the center of that story.

FORD’S THEATRE: We’re thrilled that you’re our first Legacy Commissions playwright to receive a full production, after our workshops earlier this year. Why is it important for Ford’s to give playwrights this artistic incubator to develop new historical dramas?

CLEAGE: Working at Ford’s Theatre is a great honor. The decision by the Ford’s leadership to not simply allow this sacred space to stay stuck in the one tragic moment that defines it, but to allow it to become a living, breathing place that brings Americans together to consider not only our shared past, but the present-day challenges that we face is a profound one. It has always struck me as particularly moving that the last moments of President Lincoln’s life were spent at the theater and that the assassin who changed the course of our history by violence was an actor. I think allowing playwrights to do this kind of work at Ford’s is a living, breathing tribute to the complexity of that historic moment.

FORD’S THEATRE: A diverse range of citizens in Atlanta comes together in collective memory to tell this story. And Maynard himself said that his candidacy was a “candidacy of unity” when he first ran against Herman Talmadge. What is significant about the unity that Maynard championed?

CLEAGE: There can be no real progress in American life until we are able to stop separating ourselves by race, by class, by gender and sexual identity. I think that Maynard’s ability to reach out to people across all those imaginary lines and make them feel seen and understood and included was one of the amazing things about him. He was able to talk to everybody! He respected people who didn’t agree with his politics because, I believe, he could see past all those differences and see them as human beings who needed to find a common vocabulary in order to communicate honestly with each other, find common ground and move forward together. I am so sure that if he were alive today, he would be honored to see this play on the stage at Ford’s. I also believe he would be proud that it was written by his favorite speechwriter!

Something Moving: A Meditation on Maynard runs September 22, 2023 — October 15, 2023. Learn more and get tickets now!

One Clerk’s Quest to Save History

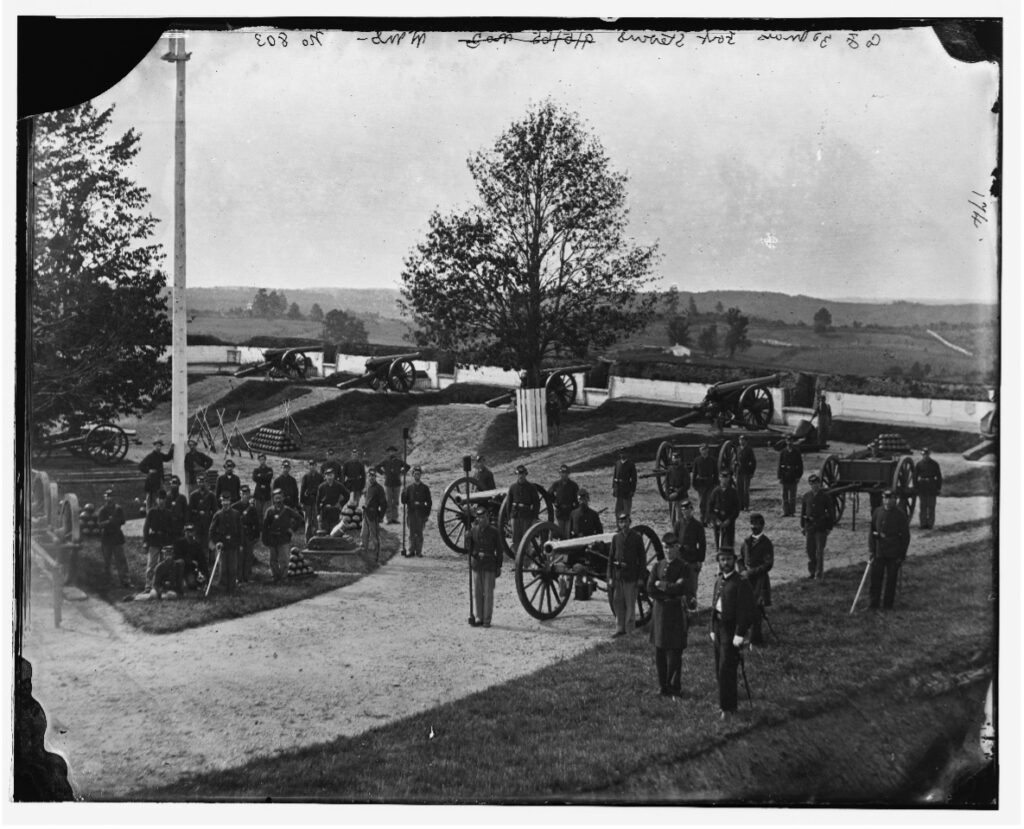

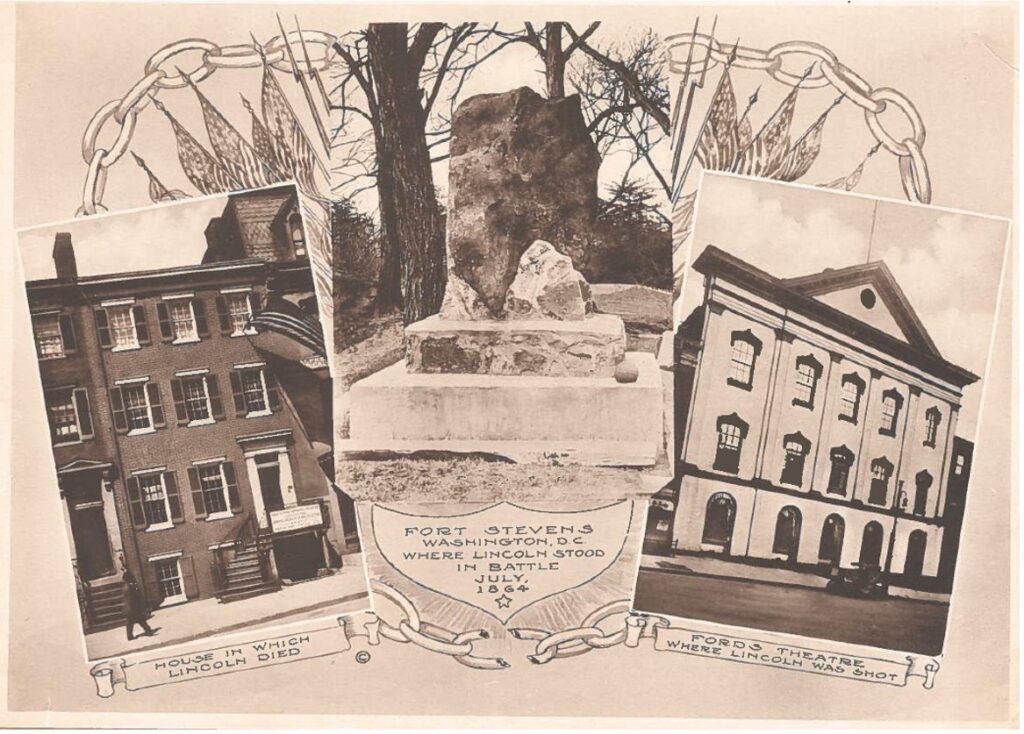

Ford’s Theatre is today an established destination for exploring Abraham Lincoln and his legacy. But did you know about the building’s post-assassination history as a warehouse for the Pension Bureau and the role of one Pension Bureau clerk in the preservation of a memorial to Lincoln at Fort Stevens? As we approach the anniversary of the Battle of Fort Stevens, learn about Pension Bureau clerk and Civil War veteran Lewis Cass White.

For Lewis Cass White, Ford’s Theatre was more than a warehouse with a tormented history: it was a powerful reminder of his connections to Lincoln and the danger he faced during the war. White’s service during one of the war’s least known – but most consequential – battles at Fort Stevens in Washington, D.C. would set the course for the rest of his life.

The Battle of Fort Stevens, fought over two sweltering July days in 1864 inside the nation’s capital itself, is not as well-remembered as other engagements, such as Gettysburg or Shiloh. Fought just five miles away from the White House and the Capitol, Fort Stevens was the only Civil War battle to take place inside the nation’s capital. Although small in scale compared to more remembered engagements, White considered it vitally important to the history of President Abraham Lincoln and the war: “Had the Capitol fallen into the hands of the enemy, if but for a day, who can measure the disaster, or compute the results?” White wrote in 1906.1

Lincoln’s role in the battle was just as important to its unthinkable contingencies. The president’s proximity to the fighting – and natural curiosity – motivated him to travel back and forth between duties at the White House and Fort Stevens to review the battle’s progress.

As the president’s six-foot-four frame (and telltale hat) peeked over the parapets of Fort Stevens, one rebel sharpshooter fired in his direction on July 12, 1864. The bullet passed within feet of the president, missing him but striking a nearby surgeon, Cornelius Crawford. The incident remains the only time a sitting president has come under direct enemy fire in battle.

The Tragic Foreshadowing

Lincoln’s proximity to the heat of battle was indicative of his cavalier attitude towards his own safety. This defiance foreshadowed the tragedy at Ford’s Theatre less than a year later.

White, a veteran of Fort Stevens, was in a hospital in Philadelphia recovering from a vicious hand wound when he first heard that Lincoln had been killed in April 1865. He and other wounded comrades took part in the public mourning when they filed past Lincoln’s remains in Independence Hall. The young sergeant made a vow to his diary: “Let us imitate his virtues and hand his name to our posterity … his virtues and noble principles will still live.” White spent the rest of his life referring to his fallen commander-in-chief as “the Martyr Lincoln” or “the Immortal Lincoln.”2

When White returned to Washington, D.C. the following year, Lincoln and the danger posed to him during his presidency was never far away. In fact, White’s first D.C. residence when he joined the staff of the Pension Bureau in 1866 was less than one block away from Ford’s Theatre.

“Fighting the Battles Over Again”

For decades, White worked his way up the chain. By 1901, he could finally purchase his own house. His choice? A parcel of land directly adjacent to the sagging remains of Fort Stevens. He lived there the rest of his life “fighting the battles over again,” as he called it. By then, Fort Stevens was a dilapidated and mostly forgotten reminder of the hot, tense battle of 1864.

Remembering the oath he made to his diary, White sought to preserve the fort and its memory, especially the story of Lincoln’s near miss. He helped found the Fort Stevens Lincoln Memorial Association to help raise awareness and funds.

Just one month before his death in 1916, White extolled surviving comrades that “there are not too many memorials now to President Lincoln, but where is a place more worthy of preservation … than the spot where he stood in battle, exposed to the fire of the enemy and at the risk of his life.”3 For White and others, Lincoln’s bravery facing danger at Fort Stevens was a counterpoint to the cowardly way he was killed at Ford’s Theatre, with his back turned, completely unaware of his assassin.

White invited surviving veterans to share their version of what happened with Lincoln at Fort Stevens. Many veterans admitted that so many years after the fact, White’s request “will test an old man’s memory,” but his detective work has been the basis for how modern historians have reconstructed the battle. One account even came from someone intimately connected to it: Cornelius Crawford, the surgeon who had been shot by the bullet likely meant for Lincoln and survived to tell the tale.

A Lincoln Memorial

After so much time, these accounts naturally differed. What many have in common was the close association each veteran drew between the Fort Stevens story and their poignant memories of when and how they learned Lincoln had been killed. One respondent, George Jewett, who would later take part in the manhunt for Lincoln’s killers, recalled how a comrade was present at Ford’s that terrible night.

When Jewett forwarded the news to his commanding officer, he was told that “I had just been having a bad dream.” Even 50 years later, shades of regret and trauma lingered for these veterans.

White’s vision of a permanent memorial to Lincoln at Fort Stevens in the form of a heroic statue did not happen. But he and his undeterred comrades did what they could: in 1911, they erected a large boulder at the approximate spot where Lincoln came under fire, based on White’s own investigation.

Lewis Cass White did not live to see Fort Stevens destroyed to make way for new development. A Civilian Conservation Corps project rebuilt part of Fort Stevens in the late 1930s. Modern visitors can still experience this resurrected piece of history, and local Washingtonians continue to commemorate this important slice of Civil War memory. Among the things visitors can still see is the boulder Lewis White Cass and other aged veterans proudly placed more than a century ago, a profound testament to one Pension Bureau clerk’s quest to hand Lincoln’s name to posterity.

Ford’s Theatre is indebted to Kathryn Forbes for sharing the Lewis Cass White collection for this story.

Citations

1. Lewis Cass White to unknown Senator, 21 May 1906, in As I Remember: A Civil War Veteran reflects on the War, ed. Joseph Scopin (Scopin Design, 2014), 71.

2. Lewis Cass White diary, 23 April 1865, private collection.

3. Lewis Cass White to surviving members of 6th Corps, July 1916, in As I Remember, 86.