Changing Perceptions: Teaching Lincoln and Reconstruction

When I was in elementary, middle and high school, I was always excited when we reached the Civil War unit in history classes.

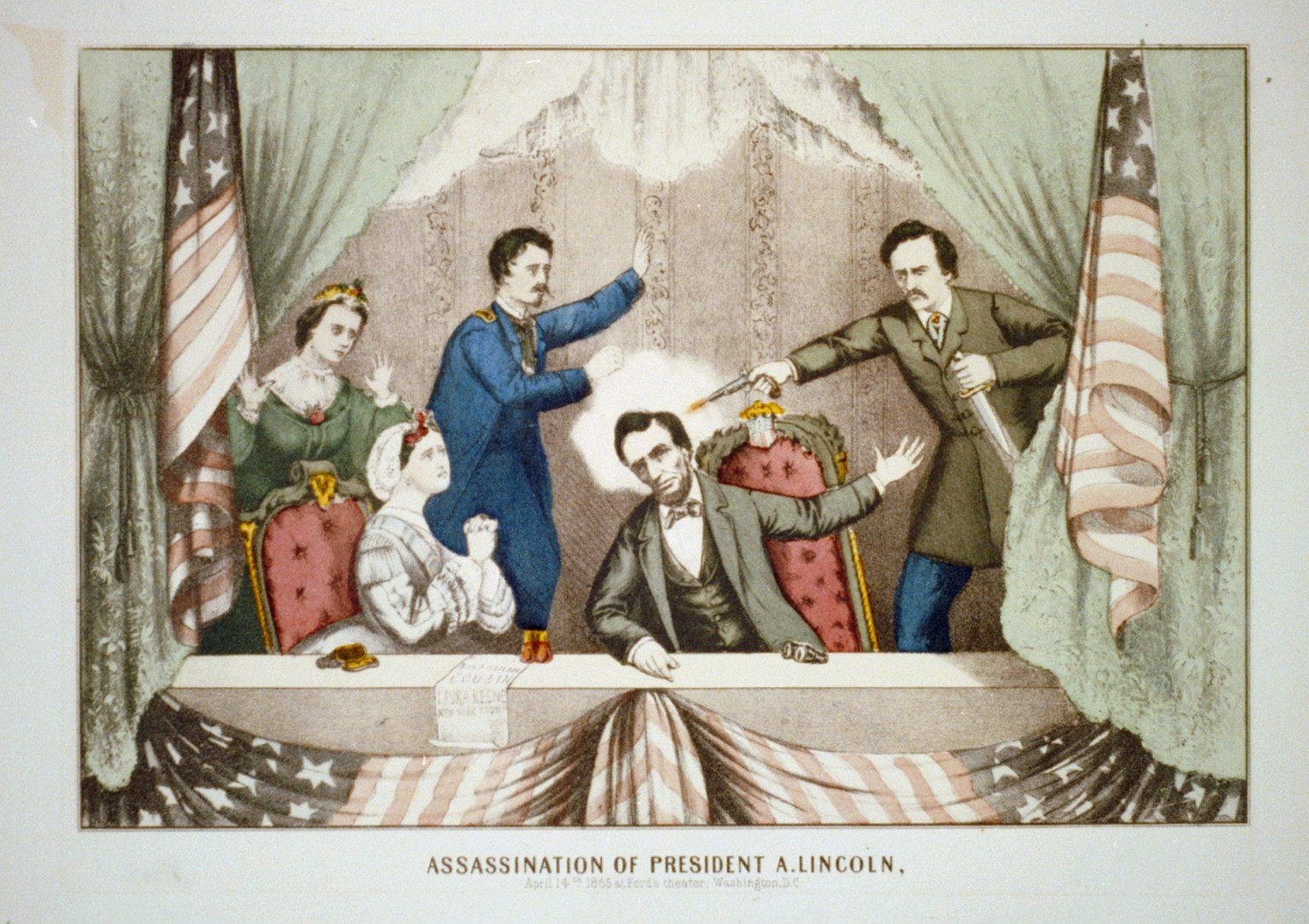

But I’ve since come to realize that these learning experiences always happened the same way. The teacher would cover Fort Sumter, talk about generals like Ulysses S. Grant and Robert E. Lee, maybe mention the battle of Gettysburg as the war’s turning point, discuss Lee’s surrender at Appomattox, and then promptly end the unit with the assassination of Abraham Lincoln.

What about Reconstruction?

Reconstruction was addressed fleetingly, time permitting, and most years we skipped right to a unit about World War I. Reconstruction was explained to me as a few years of struggle in the South, and that the country was eventually unified. Is this really the whole story, one might ask? Are students getting a full understanding of Reconstruction?

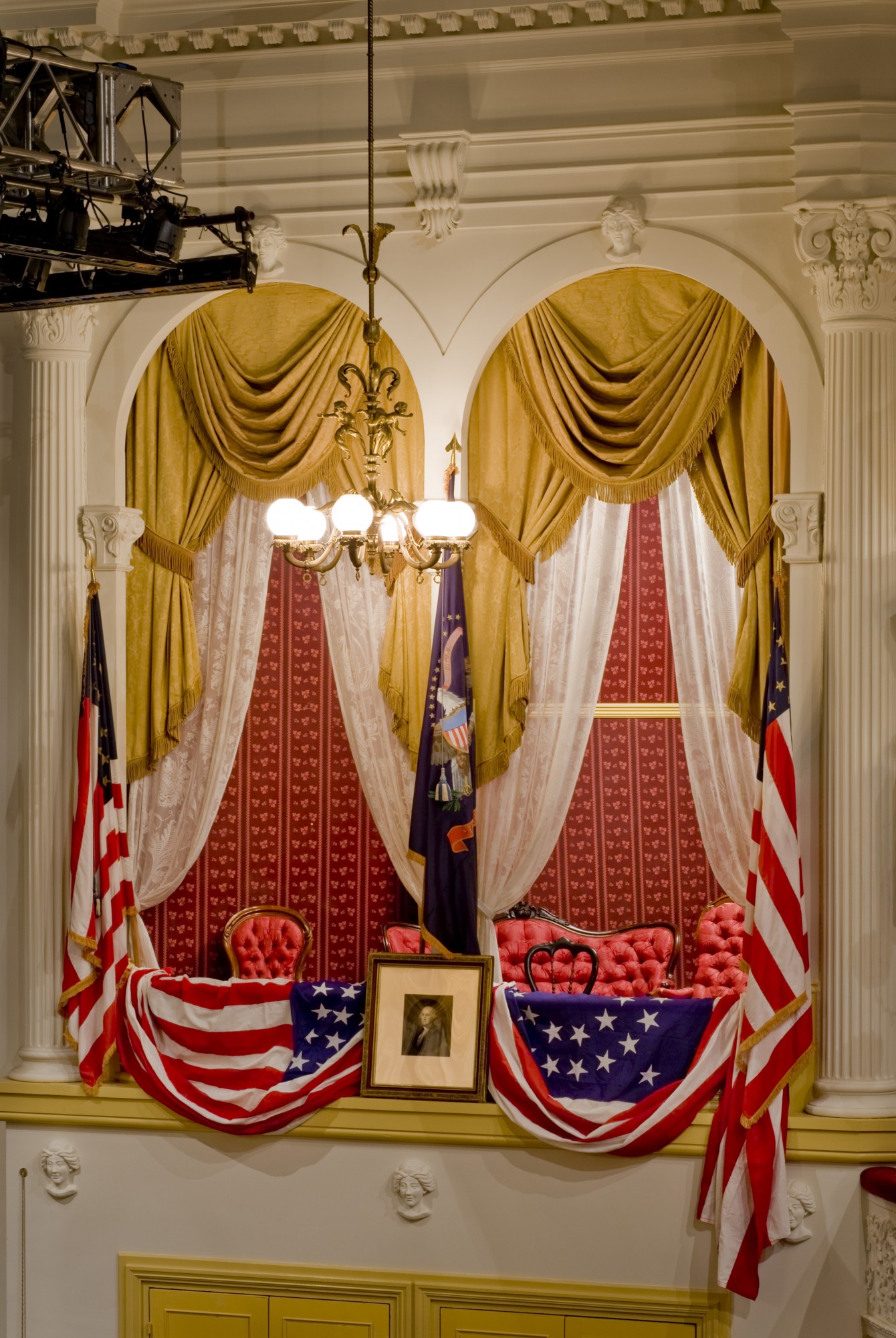

During my summer internship at Ford’s Theatre, I have participated in some preliminary interpretive planning meetings. This has changed my mind about how I think of and talk about the end of the Civil War. As I saw in my own classes, it is not uncommon to hear of Lincoln’s assassination as the ultimate conclusion to the Civil War. But during our meetings at Ford’s, we’ve discussed reframing the Lincoln assassination as the beginning of Reconstruction, a time in which the Northern states tried to reintegrate the Southern states back into a new United States, rebuilt on the ashes of the old.

Staff thinking on this comes in part from Martha Hodes’s book Mourning Lincoln. She argues this in her conclusion, saying, “The blast of the deringer at Ford’s Theatre on the night of April 14, 1865, was the first volley of the war that came after Appomattox a war on black freedom and equality. That war still ebbs and flows in American history, a century and a half after the assassination of President Abraham Lincoln.”

Greg Downs makes a similar argument in his book, After Appomattox. Downs argues that the war did not end with the Confederate surrender but lasted much longer, as federal troops occupied formerly Confederate states as the Ku Klux Klan and similar guerrilla groups terrorized black citizens throughout most of the South.

Booth’s Plot Revisited

How does this change our understanding of the Lincoln assassination?

John Wilkes Booth’s conspiracy to kidnap Abraham Lincoln and hold him for ransom changed to assassination because of a speech Lincoln gave at the White House on the night of April 11, 1865, to a large crowd that had gathered below Lincoln’s window. The speech was about the future and Lincoln’s vision for Reconstruction.

One phrase struck a nerve with Booth, who was in the crowd that night: “It is also unsatisfactory to some that the elective franchise is not given to the colored man.” Lincoln then added, “I would myself prefer that it were now conferred on the very intelligent, and on those who serve our cause as soldiers.”

In response to Lincoln’s speech, John Wilkes Booth turned to his fellow conspirator Lewis Powell and was reported to have said, “Now, by God, I will put him through. That will be the last speech he will ever make.”

Reconstruction through the Lens of Lincoln’s Assassination

What many people do not to realize is that Booth did not assassinate Lincoln because the Confederacy lost the war (though he was upset about that). Booth assassinated the President because Lincoln suggested giving African Americans who had fought in the war the right to vote. Booth was a racist and a white supremacist, and thus the notion of equal voting rights among whites and blacks—even if Lincoln wasn’t yet prepared to go as far as equal rights—was his reasoning for killing our 16th president.

When we look at the Lincoln assassination from this point of view, we can see the assassination as a precursor to the decades of racial oppression and inequality that would follow during Reconstruction and even up to today.

In his proclamation to officially end the Civil War on August 20, 1866, President Andrew Johnson stated, “I do further proclaim that the said insurrection is at an end and that peace, order, tranquility and civil authority now exist in and throughout the whole of the United States of America.” While the fighting might have officially ended, there was no peace in the South. Southern governments subjected African Americans to Jim Crow, state-sanctioned, unjust imprisonment, family separation and violence, even after the passage of the 14th and 15th Amendments, which granted all men, regardless of race, the right to vote. Congress did not officially declare the war ended until 1871.

As a future educator, I would like to say that curricula have changed to be more inclusive and offer diverse accounts of American history. Sadly, as Michael Conway points out in his article in The Atlantic, this is not always the case. Conway asserts that students are taught “a set narrative…a single, standardized chronicle of several hundred pages.” We too often teach a whitewashed version of history, written from the white, male perspective. It is our job as educators to present students with a history that is told through the lenses of all who were present by providing diverse viewpoints.

A New Framework

In terms of the Lincoln assassination, this means, like Hodes suggests, reframing the assassination as the start of a long and brutal war to prevent racial equality that many times gets skipped or overlooked in classrooms. By shifting the paradigm, students will be able to connect the tragic events at Ford’s Theatre with continuing fights for social justice that are still happening today. Lincoln’s legacy is not just one of reuniting the Union (as represented in the Lincoln Memorial) but also of advocating for freedom and civil rights.