Investigating Washington, D.C.’s Emancipation Memorial

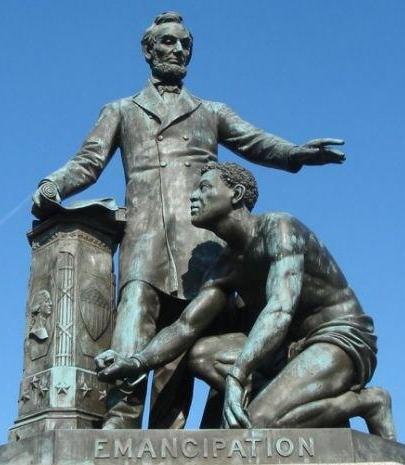

I recently had dinner with some friends who live a mile East of the U.S. Capitol near Lincoln Park. The conversation found its way to Lincoln (as it usually does when I’m in the room) and “that problematic statue in the park.” The statue in question is The Emancipation Memorial, also known as the Freedmen’s Memorial. To our 2020, millennial eyes, the Emancipation Statue is indeed problematic. A powerful, white, Abraham Lincoln stands over a kneeling black man.

I visit the Emancipation Statue every summer with teachers in our professional development institute, Set in Stone: Civil War Memory, Monuments and Myths, and I spend a lot of time thinking about it.

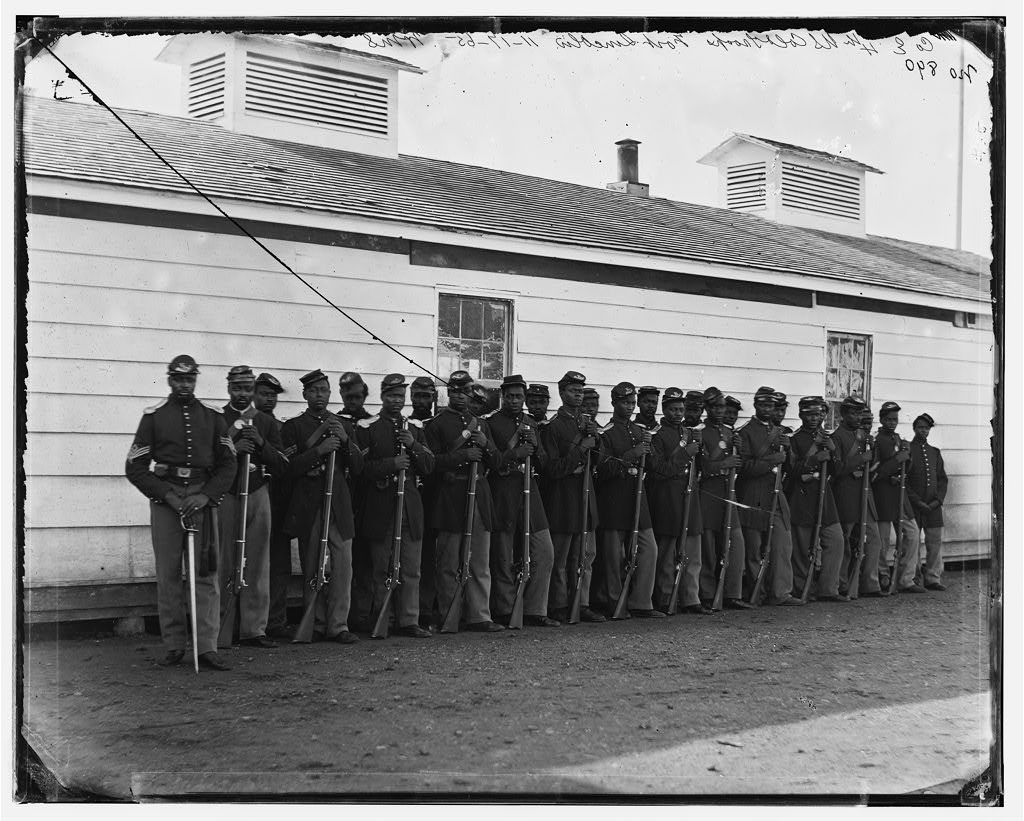

In it, Lincoln appears to be single-handedly emancipating a man. Current scholarship shows us, and I try to emphasize this on every tour I give at Ford’s, that Lincoln did nothing single-handedly. Hundreds of thousands of African Americans self-emancipated. Nearly 200,000 African Americans fought for freedom as part of the United States Colored Troops (USCT). Abolitionists advocated for an end to slavery for hundreds of years. Knowing these facts adds to my own discomfort when viewing the statue: I see a misrepresentation of how emancipation came to pass.

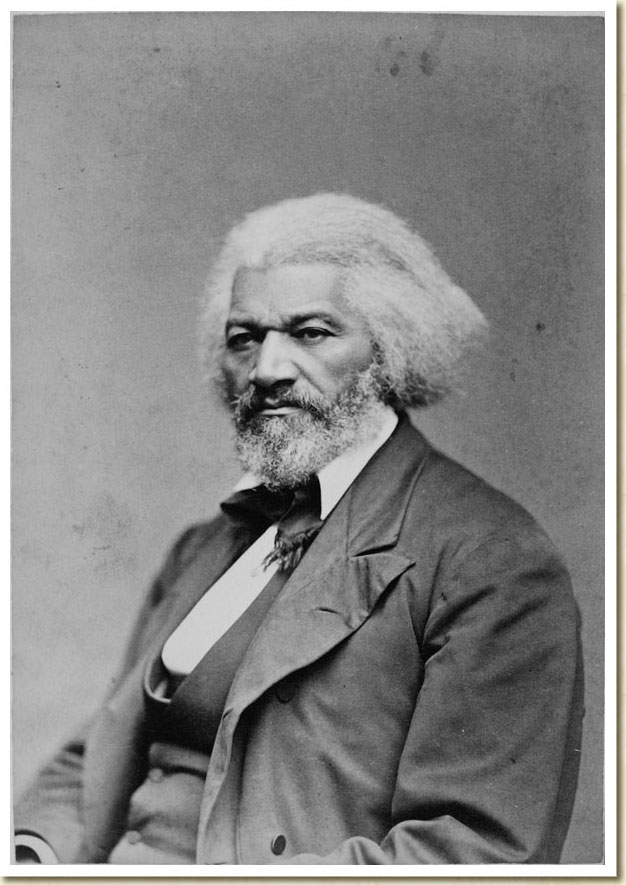

With the teachers, we use a “close-looking strategy” to analyze the statue. Close-looking involves three parts: Observe, Question, Reflect. We also do a close-reading of the speech Frederick Douglass gave at the unveiling of the statue in 1876. These strategies help us unpeel the layers of time, review when and how this statue came to be and consider how people may have felt at the time.

Observe: What do you see?

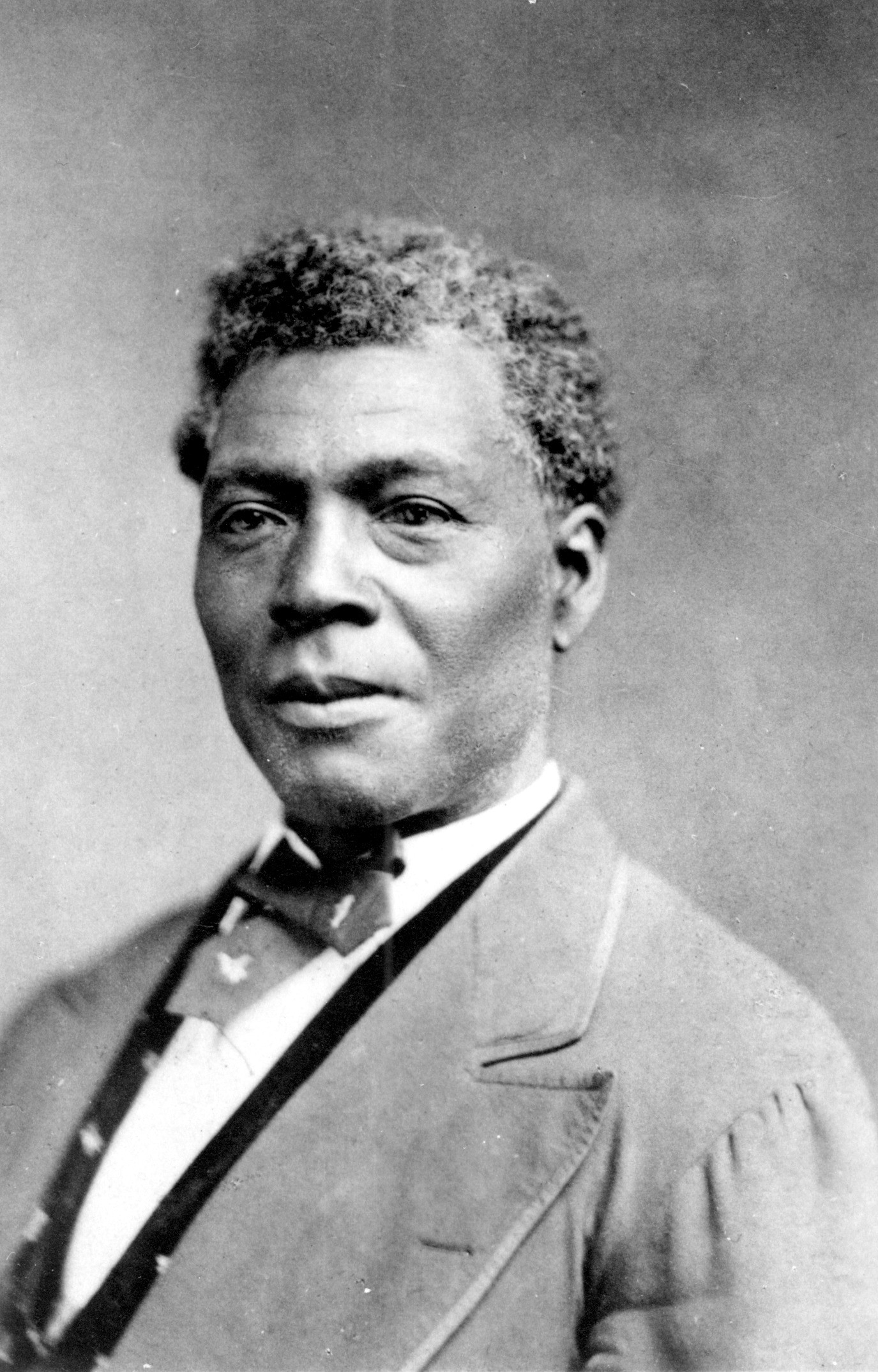

Abraham Lincoln stands over a crouching African American man. Thomas Ball, a white, American sculptor working in Munich, created the statue. At the time, the “kneeling slave” was a familiar visual motif. Abolitionist medallions depicted an enslaved man kneeling with wrists shackled, saying, “am I not a man?” You can find this imagery used throughout abolitionist papers for decades preceding the Civil War. Ball took the familiar and created a variation on it. The black man depicted is not a generic face, but a portrait of Archer Alexander.

Alexander was born enslaved in Virginia and was taken to St. Louis, Missouri. He escaped slavery in February 1863 after providing intelligence to Union Troops. Alexander moved back to St. Louis where he was hired by William Greenleaf Eliot, an abolitionist. Alexander finally secured his freedom under the protections of the Emancipation Proclamation in 1864.

Talk about being in the right place at the right time: Eliot, who selected the artist, also suggested Alexander as model.

Alexander is depicted in a crouched position; his right knee is lifted from the ground; his face is turned upward. Chains lie broken, hanging from his wrists. His right hand is clenched in a fist. He does not wear a shirt. He is muscular. Despite the lower position, Alexander’s pose is not passive.

Here, let’s question and reflect: Is he kneeling, or is he preparing to stand? When looking at Alexander’s form, is he naked and in a vulnerable state? Or is he bare-chested and strong, like an athlete? Perhaps you see something else?

Lincoln stands, left hand stretched out over Alexander’s head, right hand gripping the Emancipation Proclamation. The Proclamation is supported by a plinth (a heavy supportive structure common in statues). The plinth depicts patriotic symbols of the United States: a profile of George Washington (we even have a picture of Washington at Ford’s), fasces– a bundle of reeds strapped together representing the union as stronger together than alone– and a shield with the stars and stripes.

The statues towers over the observer. To this day, we all must look up at Lincoln.

Question: Who spoke at the dedication and who attended that event?

Frederick Douglass was the keynote speaker at the dedication of the Emancipation Memorial, on April 14, 1876, and thousands of African-Americans paraded through Washington City east from the Capitol toward Lincoln Park.

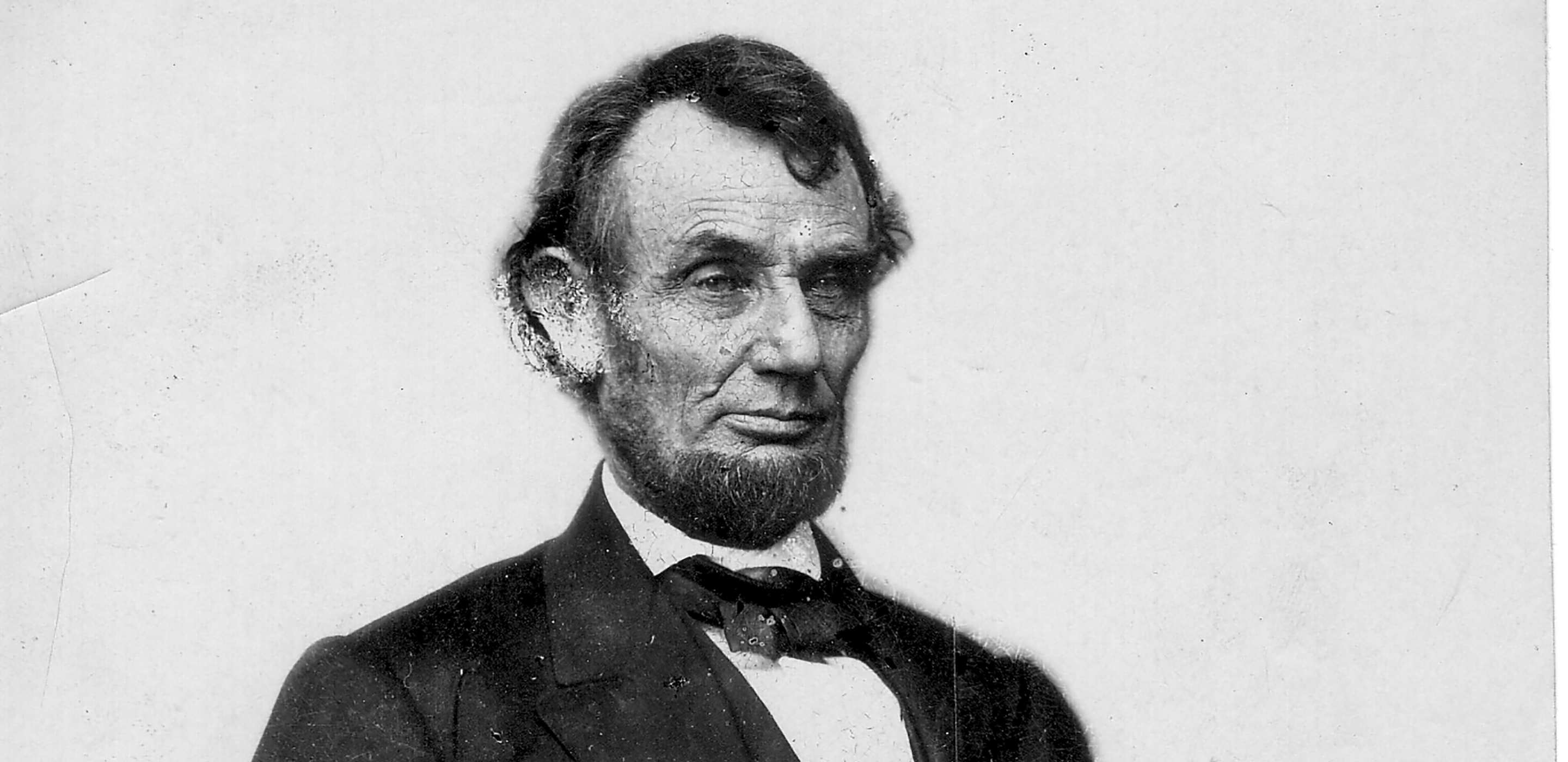

Listening to Douglass at the dedication were President Grant, his cabinet, the Supreme Court, members of Congress and the U.S. Senate and thousands of Washington citizens, black and white. Douglass delivered a tremendous speech which shook those that heard it. Astonishingly, he spent the first third of the speech criticizing Lincoln.

Abraham Lincoln was not, in the fullest sense of the word, either our man or our model… He was preeminently the white man’s President, entirely devoted to the welfare of white men. He was ready and willing at any time during the first years of his administration to deny, postpone, and sacrifice the rights of humanity in the colored people to promote the welfare of the white people of this country…You are the children of Abraham Lincoln. We are at best only his step-children; children by adoption, children by forces of circumstances and necessity.

Frederick Douglass

But then Douglass praises Lincoln, for doing what no president had dared do before: ending slavery in the United States.

“[U]nder his wise and beneficent rule we saw ourselves gradually lifted from the depths of slavery to the heights of liberty and manhood;…under his rule, … about as soon after all as the country could tolerate the strange spectacle, we saw our brave sons and brothers laying off the rags of bondage, and being clothed all over in the blue uniforms of the soldiers of the United States; … under his rule, and in the fullness of time, we saw Abraham Lincoln, … penning the immortal paper, which, though special in its language, was general in its principles and effect, making slavery forever impossible in the United States. Though we waited long, we saw all this and more.”

Who paid for it?

The memorial was paid for with funds donated by African Americans, many of them formerly enslaved and veterans of the United States Colored Troops. A woman named Charlotte Scott used her first $5 earned in freedom to kick-off the fund-raising campaign. African-Americans raised nearly $17,000 for the statue.

According to the National Park Service: “The campaign for the Freedmen’s Memorial Monument to Abraham Lincoln, as it was to be known, was not the only effort of the time to build a monument to Lincoln; however, as the only one soliciting contributions exclusively from those who had most directly benefited from Lincoln’s act of emancipation it had a special appeal.” [See their website here.]

The funds were managed by the Western Sanitary Commission. Based in St. Louis, MO, the Western Sanitary Commission was founded by white abolitionists, including William Greenleaf Eliot, and supported Union relief and abolitionist efforts during the Civil War. It continued to support Freedmen and Union veteran causes for 20 years afterwards.

Congress, upon accepting the statue from the “colored citizens of the United States,” appropriated an additional $3,000 to build the stone pedestal upon which it stands.

Reflect: Where does that leave us now?

The Emancipation Memorial is a representation of how a particular group of people were remembering Lincoln in the decade after the Civil War. It is worth noting that this is a monument to “Lincoln, The Great Emancipator,” not “Lincoln, Savior of the Union,” as is the Lincoln Memorial on the National Mall. And while many African Americans loved Father Abraham and revered him as an almost sacred figure of deliverance, there were plenty of people who knew full well that Abraham Lincoln hadn’t pulled off emancipation on his own. Harriet Hosmer, a white, American sculptor, proposed a grand, multi-tiered memorial depicting Lincoln and several African Americans, including soldiers of the USCT; but her design was rejected because it was too expensive. Douglass himself didn’t care for the statue. Just days after the dedication, he wrote a letter to the Washington National Republican, saying “What I want to see before I die is a monument representing the negro, not couchant on his knees like a four-footed animal, but erect on his feet like a man.” A statue depicting Lincoln with the 200,000 USCT soldiers who fought for emancipation may well have been just as appreciated by the audience in 1876 as it might be today.

Perhaps our own disquietude about the statue can help us connect with the exhilarating and turbulent period of Reconstruction, and our ever-evolving understanding of the legacy of Abraham Lincoln.

Read More:

- Frederick Douglass’ Oration in Memory of Abraham Lincoln

- On Emancipation Day in D.C., two memorials tell very different stories, by Joe Heim. April 15, 2012, The Washington Post.

- The Story of Archer Alexander by Eliot, William Greenleaf.

- The Story Behind A Statue, by Candace O’Connor. The Washington Post.

Editor’s Note: This blog was updated in October 2020. Initially it stated that Frederick Douglass’s feelings about the statue were “historical hearsay.” In June 2020, Scott Sandage and Jonathan W. White uncovered and published Douglass’s letter to the Washington National Republican. Learn how it helps solve a long-standing mystery.