One Clerk’s Quest to Save History

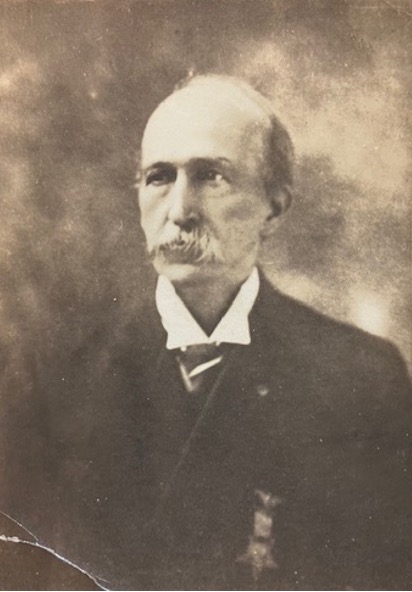

Ford’s Theatre is today an established destination for exploring Abraham Lincoln and his legacy. But did you know about the building’s post-assassination history as a warehouse for the Pension Bureau and the role of one Pension Bureau clerk in the preservation of a memorial to Lincoln at Fort Stevens? As we approach the anniversary of the Battle of Fort Stevens, learn about Pension Bureau clerk and Civil War veteran Lewis Cass White.

For Lewis Cass White, Ford’s Theatre was more than a warehouse with a tormented history: it was a powerful reminder of his connections to Lincoln and the danger he faced during the war. White’s service during one of the war’s least known – but most consequential – battles at Fort Stevens in Washington, D.C. would set the course for the rest of his life.

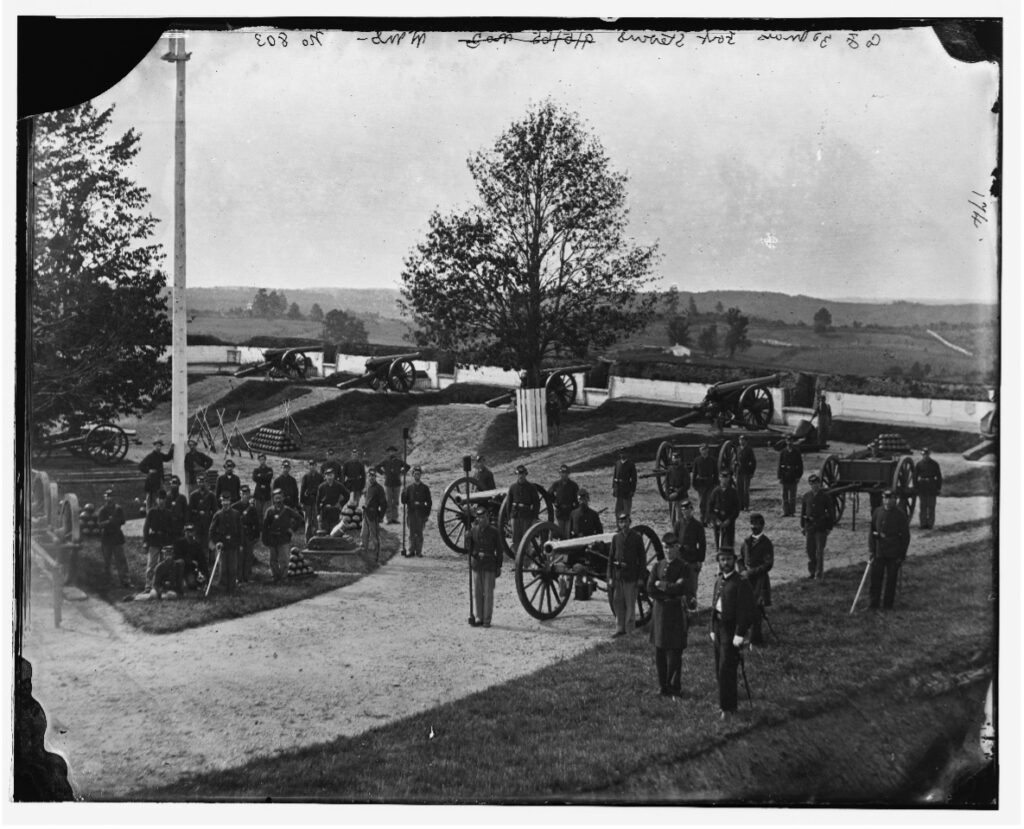

The Battle of Fort Stevens, fought over two sweltering July days in 1864 inside the nation’s capital itself, is not as well-remembered as other engagements, such as Gettysburg or Shiloh. Fought just five miles away from the White House and the Capitol, Fort Stevens was the only Civil War battle to take place inside the nation’s capital. Although small in scale compared to more remembered engagements, White considered it vitally important to the history of President Abraham Lincoln and the war: “Had the Capitol fallen into the hands of the enemy, if but for a day, who can measure the disaster, or compute the results?” White wrote in 1906.1

Lincoln’s role in the battle was just as important to its unthinkable contingencies. The president’s proximity to the fighting – and natural curiosity – motivated him to travel back and forth between duties at the White House and Fort Stevens to review the battle’s progress.

As the president’s six-foot-four frame (and telltale hat) peeked over the parapets of Fort Stevens, one rebel sharpshooter fired in his direction on July 12, 1864. The bullet passed within feet of the president, missing him but striking a nearby surgeon, Cornelius Crawford. The incident remains the only time a sitting president has come under direct enemy fire in battle.

The Tragic Foreshadowing

Lincoln’s proximity to the heat of battle was indicative of his cavalier attitude towards his own safety. This defiance foreshadowed the tragedy at Ford’s Theatre less than a year later.

White, a veteran of Fort Stevens, was in a hospital in Philadelphia recovering from a vicious hand wound when he first heard that Lincoln had been killed in April 1865. He and other wounded comrades took part in the public mourning when they filed past Lincoln’s remains in Independence Hall. The young sergeant made a vow to his diary: “Let us imitate his virtues and hand his name to our posterity … his virtues and noble principles will still live.” White spent the rest of his life referring to his fallen commander-in-chief as “the Martyr Lincoln” or “the Immortal Lincoln.”2

When White returned to Washington, D.C. the following year, Lincoln and the danger posed to him during his presidency was never far away. In fact, White’s first D.C. residence when he joined the staff of the Pension Bureau in 1866 was less than one block away from Ford’s Theatre.

“Fighting the Battles Over Again”

For decades, White worked his way up the chain. By 1901, he could finally purchase his own house. His choice? A parcel of land directly adjacent to the sagging remains of Fort Stevens. He lived there the rest of his life “fighting the battles over again,” as he called it. By then, Fort Stevens was a dilapidated and mostly forgotten reminder of the hot, tense battle of 1864.

Remembering the oath he made to his diary, White sought to preserve the fort and its memory, especially the story of Lincoln’s near miss. He helped found the Fort Stevens Lincoln Memorial Association to help raise awareness and funds.

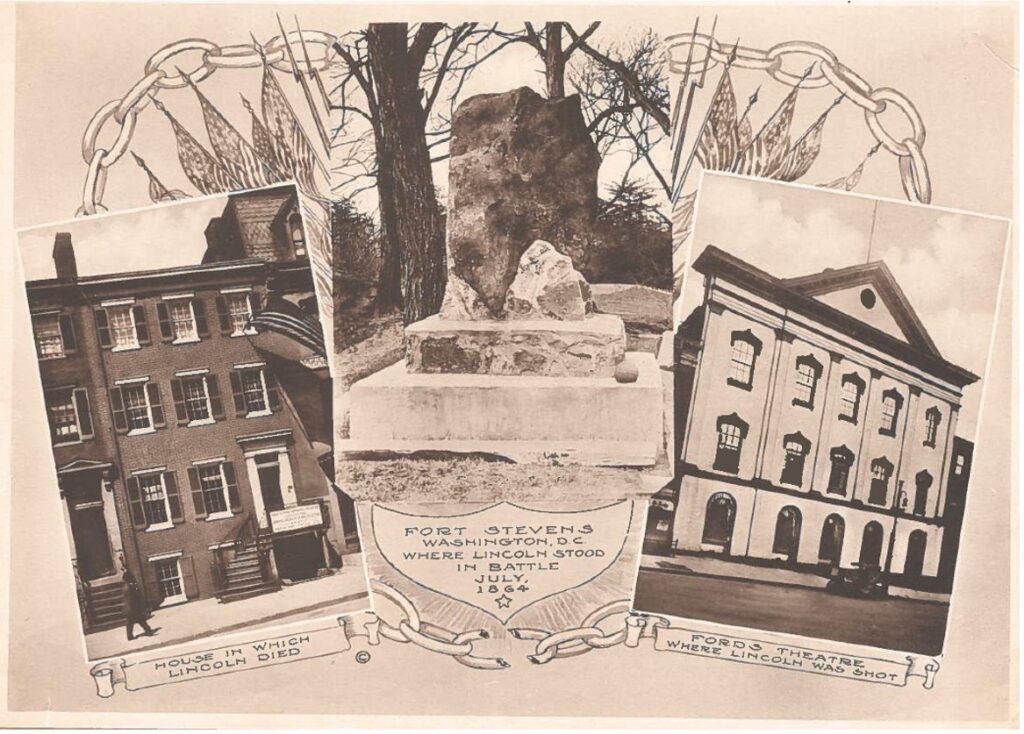

Just one month before his death in 1916, White extolled surviving comrades that “there are not too many memorials now to President Lincoln, but where is a place more worthy of preservation … than the spot where he stood in battle, exposed to the fire of the enemy and at the risk of his life.”3 For White and others, Lincoln’s bravery facing danger at Fort Stevens was a counterpoint to the cowardly way he was killed at Ford’s Theatre, with his back turned, completely unaware of his assassin.

White invited surviving veterans to share their version of what happened with Lincoln at Fort Stevens. Many veterans admitted that so many years after the fact, White’s request “will test an old man’s memory,” but his detective work has been the basis for how modern historians have reconstructed the battle. One account even came from someone intimately connected to it: Cornelius Crawford, the surgeon who had been shot by the bullet likely meant for Lincoln and survived to tell the tale.

A Lincoln Memorial

After so much time, these accounts naturally differed. What many have in common was the close association each veteran drew between the Fort Stevens story and their poignant memories of when and how they learned Lincoln had been killed. One respondent, George Jewett, who would later take part in the manhunt for Lincoln’s killers, recalled how a comrade was present at Ford’s that terrible night.

When Jewett forwarded the news to his commanding officer, he was told that “I had just been having a bad dream.” Even 50 years later, shades of regret and trauma lingered for these veterans.

White’s vision of a permanent memorial to Lincoln at Fort Stevens in the form of a heroic statue did not happen. But he and his undeterred comrades did what they could: in 1911, they erected a large boulder at the approximate spot where Lincoln came under fire, based on White’s own investigation.

Lewis Cass White did not live to see Fort Stevens destroyed to make way for new development. A Civilian Conservation Corps project rebuilt part of Fort Stevens in the late 1930s. Modern visitors can still experience this resurrected piece of history, and local Washingtonians continue to commemorate this important slice of Civil War memory. Among the things visitors can still see is the boulder Lewis White Cass and other aged veterans proudly placed more than a century ago, a profound testament to one Pension Bureau clerk’s quest to hand Lincoln’s name to posterity.

Ford’s Theatre is indebted to Kathryn Forbes for sharing the Lewis Cass White collection for this story.

Citations

1. Lewis Cass White to unknown Senator, 21 May 1906, in As I Remember: A Civil War Veteran reflects on the War, ed. Joseph Scopin (Scopin Design, 2014), 71.

2. Lewis Cass White diary, 23 April 1865, private collection.

3. Lewis Cass White to surviving members of 6th Corps, July 1916, in As I Remember, 86.