Why Ford’s Theatre Doesn’t Stage Assassination Reenactments

Any of us on staff at Ford’s Theatre, no matter what our role is, inevitably gets the question: When’s the reenactment?

Contrary to the impression a Saturday Night Live skit gave in 2014, the answer is always never.

Why not?

The answer partially lies in the site’s history. After Abraham Lincoln’s assassination in April 1865, the public was outraged and the Ford family received arson threats. Fortunately those threats did not materialize. But over the ensuing months, it became clear that the building was no longer viable as a money-making enterprise for the Fords. They leased and ultimately sold the building to the federal government.

In spite of popular fascination, there was not even a plaque recognizing the building as the site of Lincoln’s assassination until 1924. When the site opened as a museum in 1932, it was called the Lincoln Museum—devoted to Lincoln’s life.

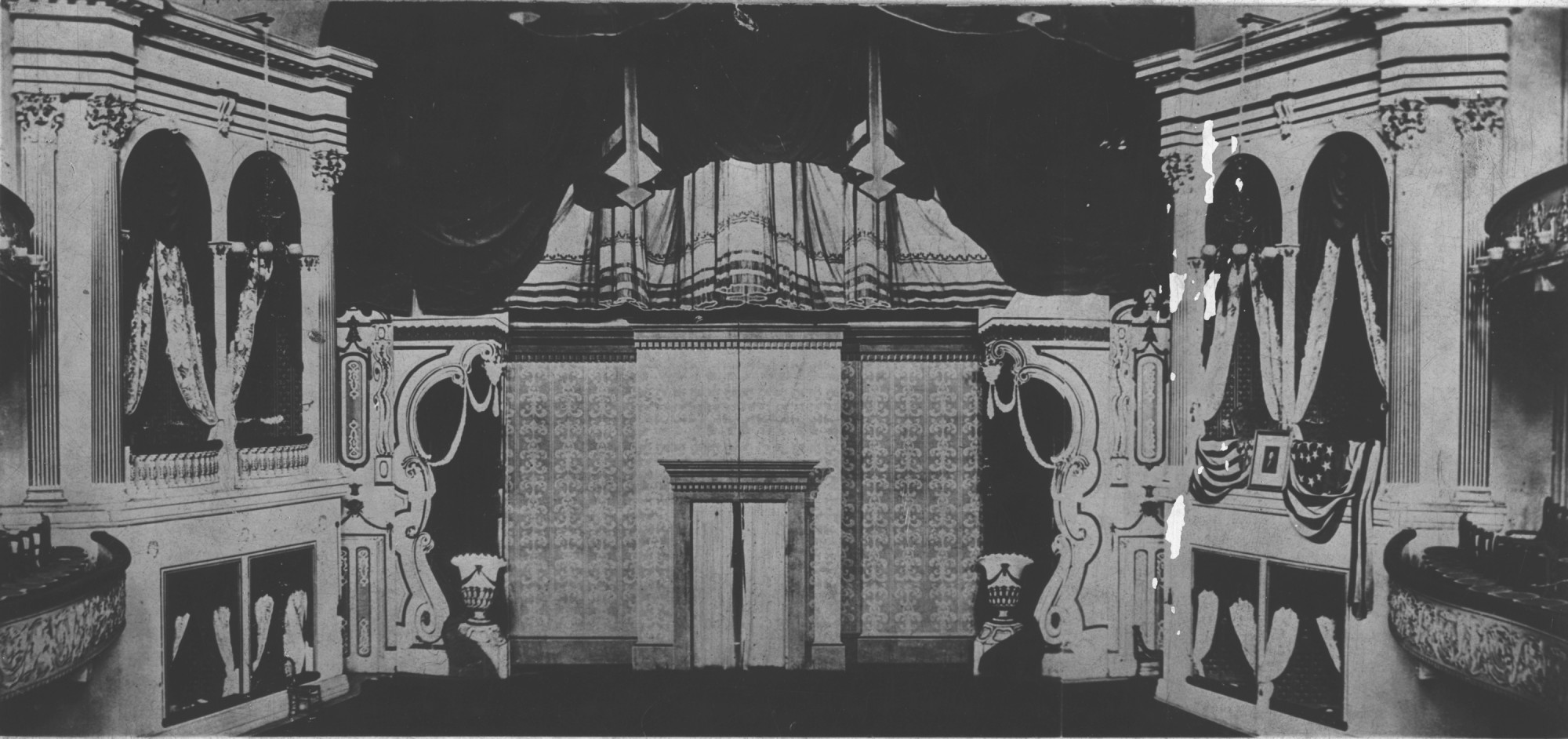

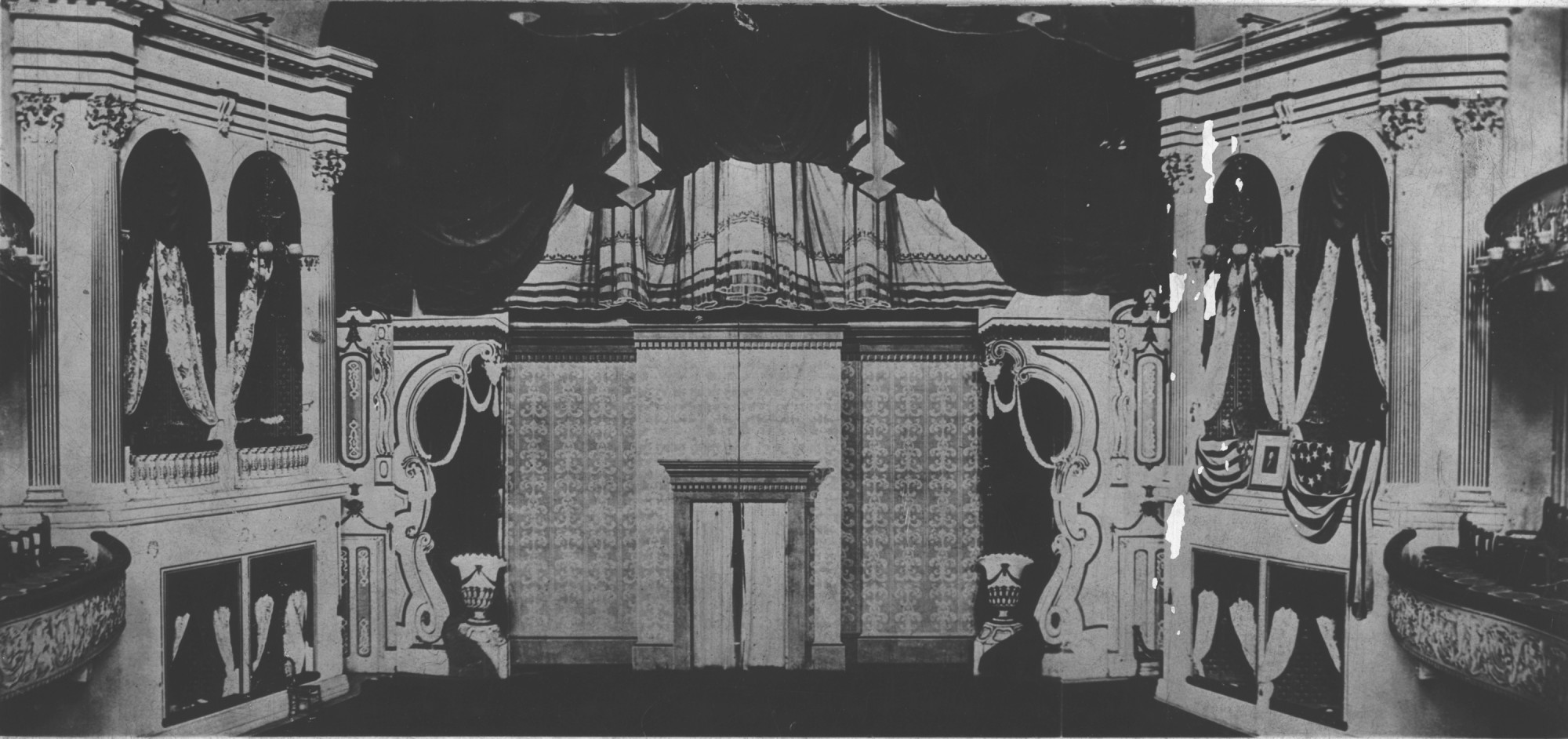

After the U.S. government announced plans to restore the building to its 1865 appearance in 1964, leaders of the Actors’ Equity Association, the union for stage actors, expressed concern that restoring the theatre without putting plays on stage would make the space a monument to what John Wilkes Booth did, rather than a place to commemorate Lincoln. Then-Secretary of the Interior Stewart Udall agreed.

Frankie Hewitt, founding director of Ford’s Theatre Society, took that idea as a mantra in bringing live theatre to the stage at Ford’s Theatre—making the site a living memorial to Lincoln through the performing arts.

As such, at Ford’s Theatre, presenting a reenactment of Lincoln’s murder is a line we are not willing to cross.

You might ask, why not—when there are reenactments at battle sites where thousands died on a given day?

That’s a fine line, one that our staff members consider. The main differences are twofold: The difference between a targeted attack on an individual life and warfare; and the educational value of such a reenactment.

An obituary for Supreme Court Associate Justice John Paul Stevens gave one of the best explanations of the difference between killing in war and a targeted assassination. As an intelligence officer during World War II, Stevens analyzed information that directly contributed to military operations. But he always expressed unease about one of those operations: When the U.S. military used information he had gathered to target an airplane carrying Japanese Admiral Isoroku Yamamoto. Why? Yamamoto was a named individual, deliberately targeted. Generally, rules of war prohibit assassination (although the particular case of Yamamoto raises questions).

For the true-crime enthusiast, there are witness statements, letters, multiple volumes of trial transcripts, and other primary sources available to research and delve into the grisly details of the Lincoln assassination.

For us at Ford’s, in the place where the tragedy actually happened, a reenactment of the Lincoln assassination would take attention from the gravity of the event and its impact on our society at large. Instead, it would focus attention instead on the macabre details of one night. It could prove kitschy, downplaying the event’s significance. It would also give John Wilkes Booth the prominence he desired in his quest to topple the United States government and preserve a system of white racial superiority.

A reenactment of a battle raises ethical questions in itself, but one can argue that such a reenactment can, at least, be valuable for understanding military strategy and tactics. It can help people understand why a pivotal event, like a battle, turned out as it did.

A focus on the details of a murder does not have similar educational value, especially when compared with the insensitivity of reenacting a murder.

The Lincoln assassination was a genuinely traumatic event for many of the people involved. Henry Rathbone, Clara Harris, and Mary Lincoln were distressed by it the rest of their lives. A reenactment could never do justice to the horror that they, others in the theatre that night, and millions of mourners, experienced.

While it is important to understand the horror of the Lincoln assassination, we do not believe in recreating it for audiences—particularly since we do not know what each one of the 650,000 annual (pre-pandemic) visitors to Ford’s Theatre have experienced in their own lifetimes. We do not wish to create a spectacle that would cause someone who had experienced or witnessed gun violence or another act of terror to relive those moments.

Rather, we explore the assassination through our play One Destiny, which recounts the assassination through the perspectives of several people who experienced it. Similarly, on the 150th anniversary of the Lincoln assassination in 2015, we staged 36 hours of programming at the historic site that evoked and commemorated the assassination. These events included a moving candlelight vigil between the theatre and Petersen House overnight on April 14-15, complete with dozens of actors in historical costume portraying witnesses to the events. But no reenactment of the murder took place.

Ford’s Theatre Society and the National Park Service believe that it is important to study why Booth assassinated Lincoln rather than how, so that we, as a collective humanity, can prevent future similar political violence. Our programs and exhibitions intentionally evoke and discuss, not reenact, Lincoln’s assassination.

David McKenzie formerly worked on exhibitions and digital history projects at Ford’s Theatre. Before coming to Ford’s in 2013, he worked at the Jewish Historical Society of Greater Washington, The Design Minds, Inc. and at the Alamo.