A Tale of Two Symbols: Lincoln and the U.S. Capitol Dome

December 2023 will mark the 160th anniversary of the statue of Freedom topping the U.S. Capitol dome. All these years later, both President Abraham Lincoln and the Capitol dome’s legacies remain connected—and questioned.

It was December 2, 1863. A large crowd stood on the U.S. Capitol’s East Plaza, heads tilted back as they looked skyward, 288 feet above them. Even amid the Civil War and frigid temperatures, hopes ran high as the last piece of a massive new bronze statue, Freedom, was deposited on top of the U.S. Capitol’s dome.

As the final piece swung into position, the raising of a Union flag signaled—success!

The crowds cheered, and cannons positioned for miles around Washington thundered a deafening salute. “Let us indulge the hope,” wrote the National Intelligencer, “that our posterity to the end of time may look upon it with the same admiration.”1

After eight years of construction during an unprecedented national crisis, the Capitol’s dome, a symbol of Union and republican government, was crowned with a monumental statue personifying freedom. Although President Abraham Lincoln did not attend the ceremony—he had a mild case of smallpox—his symbolic presence at the event was undeniable.

Just weeks previously, Lincoln spoke about a “new birth of freedom” during his famous Gettysburg Address. The statue carried his imprint; the engineer who installed it stamped “A LINCOLN PRESIDENT” on its feathered headdress, where it remains today.

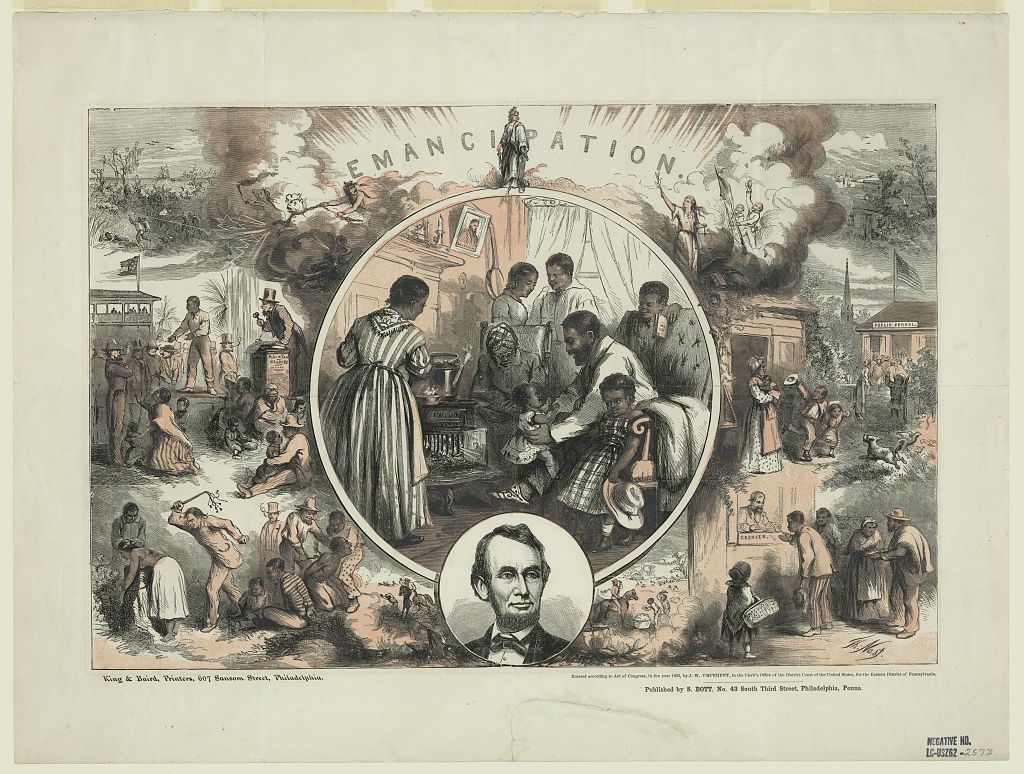

The relationship between Lincoln, the U.S. Capitol dome and freedom is a rare example of historical meaning writing itself. Tracking the evolution of the dome and the rising tide of emancipation during Lincoln’s presidency is a study of parallel growth. Their legacies are intertwined as enduring symbols of the United States and its ideals, and handy lenses to view Lincoln’s place in the history of real freedom for real people.

Which Union Would Go On?: Parallels in Construction

From the beginning of Lincoln’s administration, his destiny and the destiny of this unfinished monument seemed locked together in orbit around the gravity of events. Case in point: the physical and metaphorical progress of the dome’s construction.

Work temporarily stopped on the dome project when Confederate forces in Charleston, South Carolina, fired on Fort Sumter a month after Lincoln’s first inauguration. Pieces of white painted cast-iron laid inert around Capitol Square. Northern militias who rushed to defend the exposed Union capital city used them as barricades, expecting to defend the Capitol building from insurrection.

Once it was clear the city was at least temporarily safe from attack a few months later, work resumed. Lincoln noticed the important symbolism of the Capitol’s ongoing construction. He famously told a friend that: “If people see the Capitol going on, it is a sign that we intend the Union shall go on.”

But which Union would go on? Again, the Capitol dome reflected the times, showing the ambivalence of both Lincoln’s stance on the issue at this moment and the cruel ironies caught in the middle of war, politics and architecture.

The Building of Freedom: Parallels in Emancipation

Amid this artistic and historical contradiction, Congress passed the D.C. Compensated Emancipation Act in April 1862, freeing all enslaved people within the District of Columbia. Freedom came with a catch: enslavers were compensated for the loss of “their property.”

Although an unprecedented first step, questions remained. How would freedom come for millions of others through the South and border states like Maryland? And what would this freedom mean without legal guarantees to equal citizenship? The half-finished dome was a visual reminder of the awkward middle ground between freedom and justice the Compensated Emancipation Act represented: the promise of hope, without all the guarantees of equality.

Throughout 1862, Freedom’s construction and emancipation persisted. In October, Lincoln revealed the preliminary Emancipation Proclamation, signaling a steady but ambiguous path. By year’s end, the completed Freedom arrived at the Capitol grounds, where it waited to be placed on the dome.

Philip Reid, an enslaved man, was instrumental in the completion of Freedom. In 1863, the year the Emancipation Proclamation was issued, the New York Tribune asked: “Was there a prophecy in that moment when the slave became the artist, and with rare poetic justice, reconstructed the beautiful symbol of freedom in America?”2

Considering Freedom from April 14, 1865, to Today

On April 14, 1865, John Wilkes Booth shot Lincoln at Ford’s Theatre, a murderous attempt to prevent this reconstruction of freedom. Even in death, Lincoln cemented the dome’s importance. His body Lied in State underneath the dome and Freedom, as thousands mourned him.

Almost immediately, the country leveraged images of Lincoln, Freedom and the dome as shorthand for national reunification. But questions about the country’s future remained unanswered.

These symbols’ legacies remain unsettled today. “So did Lincoln even care about slaves?” a student asked me during their field trip to Ford’s Theatre, standing near a model of the unfinished Capitol dome.

It’s a fair question that historians continue to research and discuss—but one single blog post or field trip can’t answer it definitively. Lincoln’s words and actions are all that is left for us to assess his life and his legacy.

160 years after Freedom first stood triumphantly over the nation, the Capitol dome cannot speak for itself. It falls on us, the citizens of the country it represents, to define its meaning.

1 National Intelligencer, Dec. 2, 1863.

2 Correspondent of New York Tribune, Dec. 2, 1863, qtd. in George W. Williams, History of the Negro Race in America (New York: G.P. Putnam, 1885), 557.

Join Ford’s Theatre Education on March 4, 2024, for a virtual history talk looking deeper into the connections between Lincoln, the Capitol dome and their impact today.

Stay up to date on public programs with Ford’s Theatre Education for more discussions at the nexus of Lincoln’s history and impact today.

Blake Lindsey is the former Museum Interpretive Resources Specialist at Ford’s Theatre.