Albert Einstein and Marian Anderson’s Friendship of Happenstance

In the early 1930s, Marian Anderson was regarded as one of the greatest opera voices of all time, yet in the United States, she was mostly known in the African-American community for her interpretation of spirituals and opera arias. Despite her immeasurable talent, racism and segregation kept her from being widely known.

At six years of age, Anderson began singing at Union Baptist Church in Philadelphia. She did not begin formal music lessons until she was 15 when her community raised funds to afford her vocal training.

Not able to build a substantive career at home, Anderson followed in the steps of Black musicians who had traveled internationally to become star attractions across the European continent. Anderson took Europe by storm, selling out concert venues, wowing critics, singing for royalty and becoming daily front-page news in every country she visited. Her time in Europe turned her into an international phenomenon. The world of opera embraced her as one of their own when renowned conductor Arturo Toscanini declared to Anderson, “A voice like yours is heard once in a hundred years.”

With dozens of sold-out European concerts, extraordinary reviews and essays on her voice, and vocal abilities by musicologists around the world, Anderson returned to the United States a bona fide sensation. She began touring in the United States and, in 1937, gave a concert at McCarter Theatre—the pre-eminent concert hall in Princeton, New Jersey, at the time. In the audience that night was Albert Einstein.

While Einstein was traveling in the United States in 1933, the Nazis ascended to power. Doubtful that he would survive the academic purges the Nazis were conducting at the University of Berlin and fearing for his family’s safety, Einstein stayed in the United States and took a position at the Institute for Advanced Study in Princeton, NJ.

Anderson and Einstein met backstage after the concert and Einstein offered to escort Anderson to the Nassau Inn where she had a reservation. When she arrived with Einstein, the hotel manager denied her accommodations because of the inn’s stated “whites only” policy. Einstein invited Anderson to stay at his nearby home with his daughter for the night.

A year later, Einstein discovered that Berlin scientists had split the uranium atom, creating a fission reaction that could make an atomic bomb possible. He understood that an atomic bomb could bring about the destruction of the planet. He wrote to President Franklin Roosevelt in 1938, urging the president to initiate efforts to build a resulting top-secret program known as the Manhattan Project.

Meanwhile, Anderson continued to perform at home and abroad. When she was invited to perform as part of Howard University’s concert series in Washington, D.C., the university did not have a venue large enough for the crowds who were eager to hear her sing. Constitution Hall, with its thousands of seats, was an appropriate location, but the Daughters of the American Revolution banned Anderson from performing there because she was Black. A subsequent campaign led to Anderson’s groundbreaking performance on the steps of the Lincoln Memorial in April 1939.

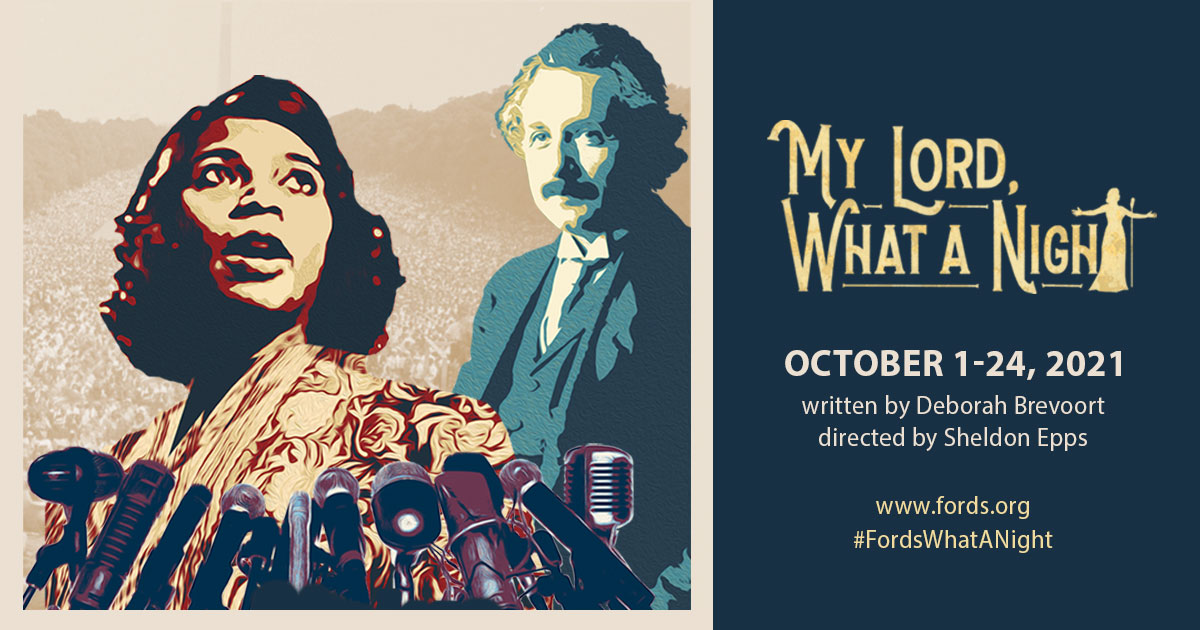

Playwright Deborah Brevoort knew of the friendship between Anderson and Einstein and chose to write the play My Lord, What a Night, framing their friendship in the context of these significant historical events. The play was initially commissioned by Premiere Stages in partnership with the Liberty Hall Museum which, through the Liberty Live Program, has a commission directive for playwrights’ intent on telling little-known stories about New Jersey.

Although Anderson and Einstein shared a great passion for music, their differences in other matters were startling: Anderson was deeply religious while Einstein was a complete agnostic; both had conflicting approaches as to how to advance civil rights—she refused to protest, choosing instead to use her gifts as a singer as an instrument of change. Einstein, meanwhile, could never keep his feelings to himself. He gave lectures at scores of universities, never missing the opportunity to compare the treatment of African Americans in Princeton to the Jews in Germany. But despite divergent beliefs, their friendship lasted until Einstein’s death on April 18, 1955, when Anderson was counted amongst his family and closest friends.