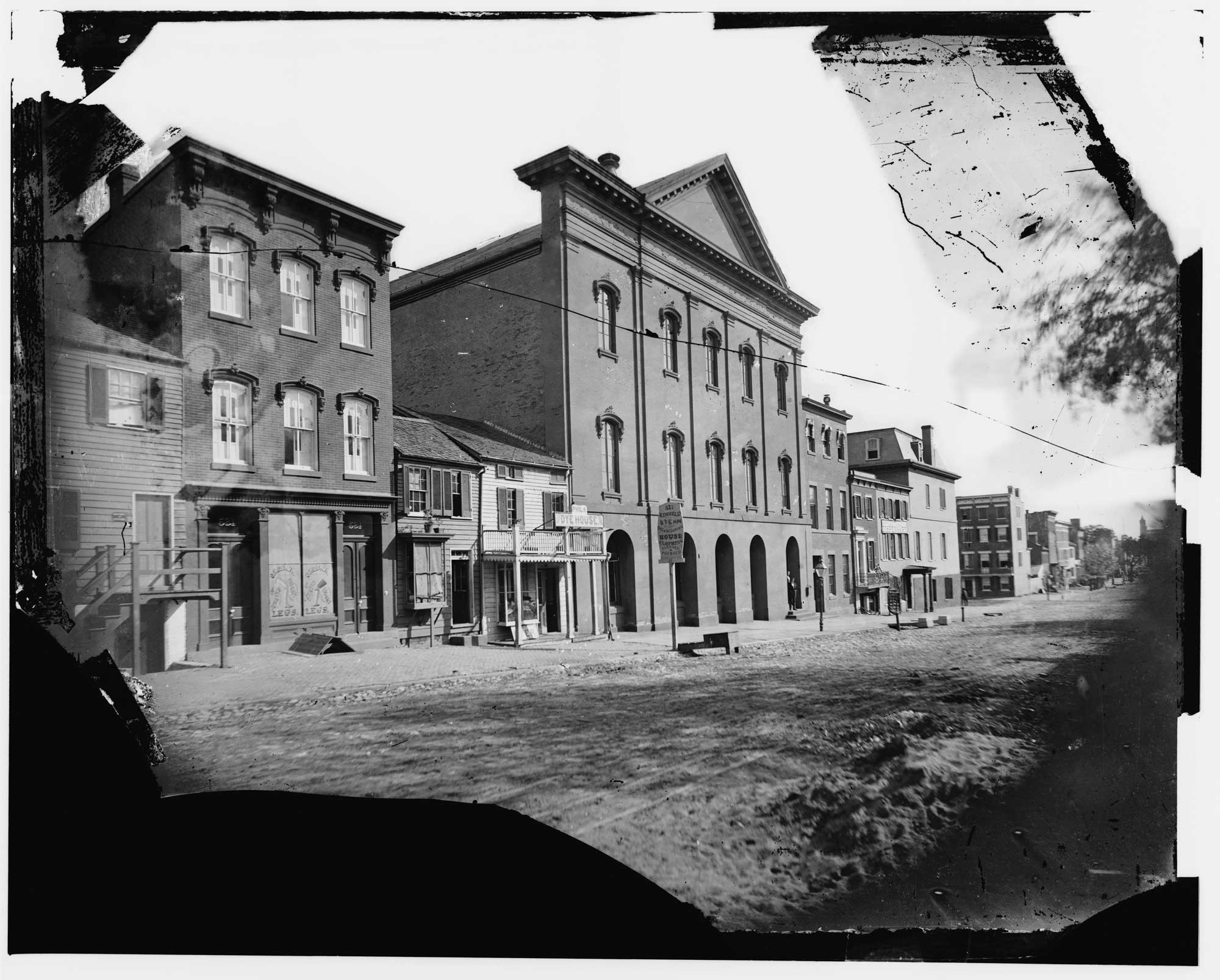

Fifty Years of Ford’s Theatre: 1968 Neighborhood Riots and Renewal

Fifty years ago, Ford’s Theatre reopened its doors as a producing theatre after the stage had been dark for 103 years. The nationally televised reopening, broadcast on CBS on January 30, 1968, marked the rebirth of Ford’s as a place to celebrate the legacy of Abraham Lincoln through theatre and education. Just two months later, Lincoln’s legacy of unity, equality, inclusion, charity and forgiveness would be severely tested in the streets of the nation’s capital.

Decades of frustration in the African-American community over segregation, housing discrimination, lack of jobs and failing public schools came to a head immediately following the assassination of Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., on April 4, 1968. Wide-spread rioting erupted in the streets of Washington.

During the next four days, 12 people were killed, 900 businesses were damaged and more than 6,000 people were arrested. According to Ten Blocks From the White House, a 1968 book written by Washington Post reporters, it took 11,600 U.S. troops to restore order to the capital city. It was the largest number of soldiers to occupy an American city since the Civil War.

The Theatre’s location at 10th and F Streets, NW, was not at ground zero of the riots, but it was not far from it. Most of the rioting took place in three predominately African-American neighborhoods several blocks north: 14th Street, NW; 7th Street, NW; and H Street, NE. Included in the 2,000 incident reports compiled by the Secret Service were looting at 10th and E (liquor store), looting at 9th and F (shoe store) and looting at 11th and G (Woodward and Lothrop department store).

While Ford’s emerged from the rioting relatively unscathed, its neighborhood did not. Many damaged businesses did not reopen. Many business owners packed up and moved to the suburbs of Washington. The once vibrant F Street shopping corridor transformed to feature boarded-up store fronts, liquor stores and adult movie theaters.

One bright spot among the blight was the 9:30 Club. The now legendary music venue’s original location was in the Atlantic Building at 930 F Street, NW, right next door to what is now the Ford’s Theatre lobby. From 1980 to 1996, the 9:30 Club featured an eclectic line up of local music, from punk to Go-Go. The club also booked up-and-coming bands from around the country. The list of bands that played the original 200-seat venue and went on to fame includes Nirvana, R.E.M., Public Enemy, the Red Hot Chili Peppers and more. The 9:30 Club shared an alley with its more famous neighbor, Ford’s Theatre. Many musicians recounted the size and number of rats–both considerable–seen in the alley after shows.

It took 30 years for the Ford’s neighborhood, and much of the city, to begin to recover from the riots. In 1992 the Shakespeare Theatre Company opened in the newly built Lansburgh Theatre at Seventh and E Streets NW. Then, in 1997 a new arena for the Washington Capitals hockey team and Washington Wizards basketball team opened three blocks east of Ford’s. This marked a transformation of the neighborhood.

In the past 20 years, countless restaurants, bars and stores have opened in the blocks surrounding Ford’s and the areas just north of where the riots took place.

Today the areas most affected by the riots are unrecognizable children of their blighted past. But the benefits of rebuilding downtown have not been shared by all. Tens of thousands of mostly young, white professionals have moved into the city, while many members of Washington’s long-standing African-American community have been priced out of Washington. Once-shuttered store fronts are now brew pubs and yoga studios. The old 9:30 Club space is now a J Crew store (and the 9:30 Club moved to the U Street Corridor. But the gulf of income inequality between whites and blacks in D.C. is greater today than it was when the first brick of frustration was thrown in 1968.

Throughout all the travails and transitions in D.C., Ford’s has remained an anchor of the 10th street neighborhood. We work every day to celebrate Lincoln’s legacy through theatre and education programs.

Jake Flack is Ford’s Associate Director of Museum Education. The native Washingtonian has fond memories of visiting Ford’s as a kid with his grandfather and going to shows at the original 9:30 Club.