I’ve Got a Secret: Evaluating Historic Truth

Every so often, we at Ford’s Theatre receive emails, calls or social media posts asking if we’ve seen a 1956 clip from the popular game show I’ve Got a Secret, in which a 96-year-old man, Samuel James Seymour, vividly recalls his memory of being present at Ford’s Theatre when President Abraham Lincoln was assassinated on April 14, 1865.

Given the inquiries about this video clip, we decided to investigate how his story holds up to historical criticism. Though many articles have taken his story at face value, we may never know whether Samuel J. Seymour witnessed the tragedy himself. When digging deeper, we found some details that can help us better understand Seymour’s story and help us consider its validity.

Eye-witness Account

Prior to his appearance on I’ve Got a Secret, Seymour gave an oral account that was published in American Weekly, seen here in the Milwaukee Sentinel on February 7, 1954.

Born on March 28, 1860, in Talbot County, Maryland, Seymour was just five years old when he and his father traveled to Washington with the owner of the plantation, George Goldsborough, “on business—something to do with the legal status of their 150 slaves.”

The previous year, Maryland had abolished slavery and states were in the process of ratifying the Thirteenth Amendment to end legal slavery nationwide. Although Maryland had outlawed slavery at the time, many formerly enslaved people maintained an ambiguous status between enslaved and free. This may be the business to which Seymour referred.

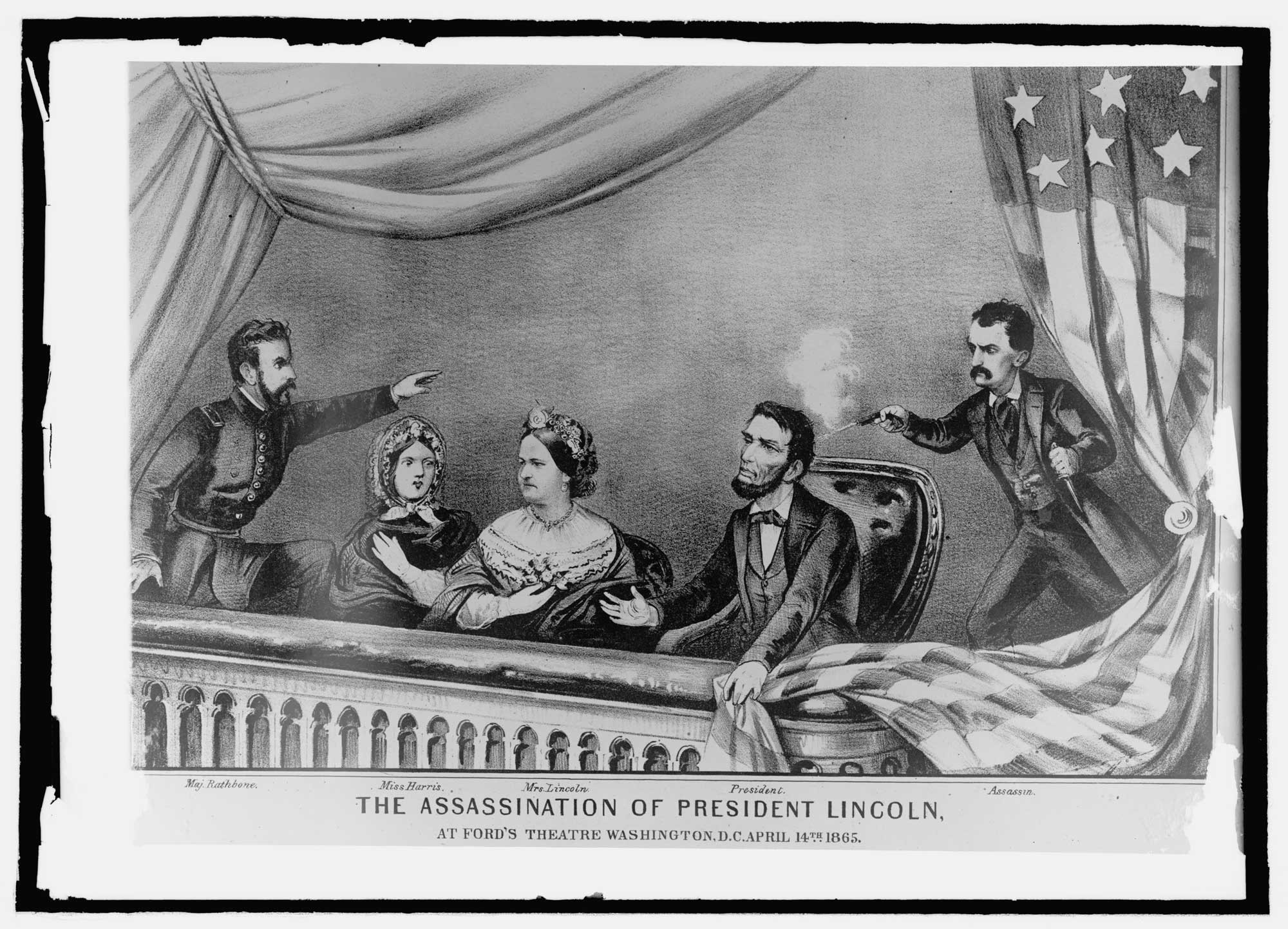

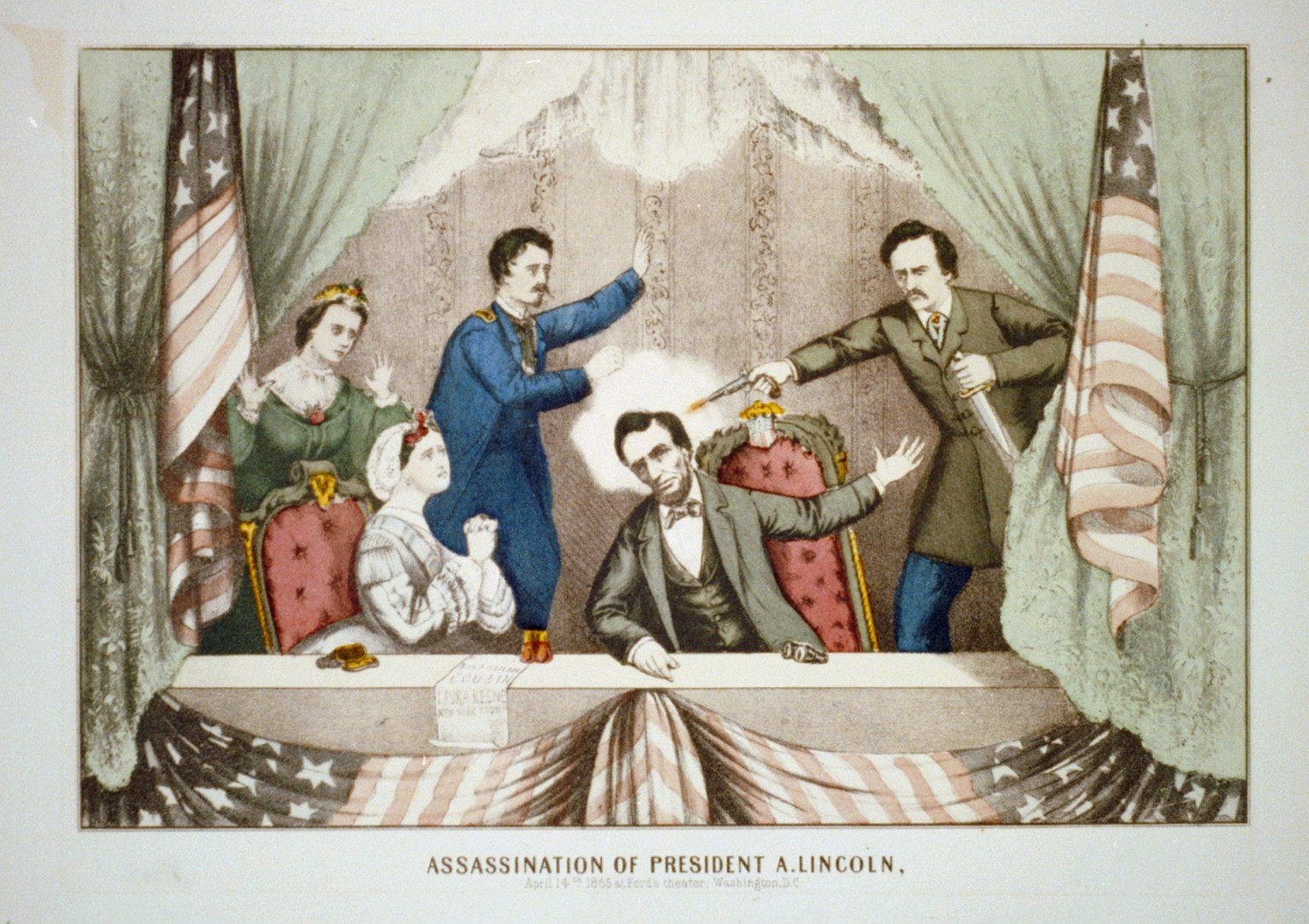

Seymour notes that his nurse, Sarah Cook, and godmother, Mrs. George S. Goldsborough, accompanied him to see Our American Cousin at Ford’s Theatre. Seymour recalls sitting in the balcony seats across from the Presidential Box and watching the President slump over and John Wilkes Booth fall from the box.

Evaluating Historic Truth

In her book Mourning Lincoln, historian Martha Hodes omits memoirs and accounts of the Lincoln assassination that were taken by witnesses later than the spring of 1865. Hodes explains that such accounts can be “extravagant descriptions” of the events and largely embellish the historical truth.

Seymour did not tell his story in a public forum until he was 94 years of age. While consistent both times he related his experience, it’s curious that he waited so long to disclose this childhood memory.

Like many historians, Randolph Hollingsworth, Ph.D., at the University of Kentucky instructs students to evaluate historical sources by considering how they hold up against something that is indisputable or generally acknowledged as true. Most articles covering Seymour’s account take his message as a certainty, but as responsible historians it’s important to investigate further.

What We Know

Today, we know of only 300 or so firsthand accounts of the Lincoln assassination, yet there were upwards of 2,000 people in attendance on April 14, 1865. Most audience members never wrote or publicized their experiences. Historians like Timothy S. Good, who compiled 100 witness accounts (including Seymour’s) in We Saw Lincoln Shot, argue that the best witness accounts came from the seats directly across from the Presidential Box. This was because those patrons likely had the clearest view to see the assassination. But at the time of the assassination, ticketed seating at Ford’s Theatre was open on each of its three levels—meaning that no documented record exists of who attended or where Seymour, or anyone else, was sitting. Thus, there are no accounts or documents proving that Sarah Goode or Mrs. Goldsborough were present at the theatre either. In essence, we must rely on a witness account given more than 50 years since the assassination.

While it is entirely plausible that Seymour had recounted his experience privately to friends and family before his I’ve Got A Secret appearance, it’s important to consider the complexity of the human mind. The delayed nature of Seymour’s public account and the age at which he relayed his experience does give us some pause. According to Psychology Today the ability to recall information and memories accurately does worsen with age.

It is likely we will never know if Samuel Seymour was truly in the audience of Our American Cousin in 1865. What do you think? Those of us who are curious about history should be skeptical of primary sources and dig deeper, comparing them to other accounts to get as close as we can to the truth of major historical events.

Melissa Queen was history and education intern for fall 2018 at Ford’s Theatre. She is a public history graduate student at Texas Woman’s University and former secondary history teacher.