Should Ford’s Display a Murder Weapon?

Sometimes when you’re doing archival research for one purpose, a document that leads to another project jumps out at you.

In early 2019, I reviewed the on-site Ford’s Theatre National Historic Site archives, researching which knife John Wilkes Booth may have used in his attack on President Lincoln’s theatre box companion, Major Henry Rathbone. When looking through the accession file (documentation related to a set of artifacts), I came upon a letter that made my jaw drop.

Should a Historic Site Display a Murder Weapon? 1931 Edition

In 1931, Lieutenant Colonel Ulysses S. Grant, III, was planning the transfer of items in the Lincoln Museum from the Petersen House building across the street to the first floor of the former Ford’s Theatre. (Yes, that Grant family—in fact, the grandson of the couple who almost accompanied the Lincolns to Ford’s Theatre on April 14, 1865.)

In that collection were more than 3,000 artifacts that collector Osborn Oldroyd had acquired in the previous 70 years. But Grant had his eyes on something outside the Oldroyd collection: Lincoln assassination conspiracy trial artifacts, including the deringer pistol that John Wilkes Booth used to kill Lincoln. This murder weapon and other artifacts had been in the custody of the U.S. Army Judge Advocate General since 1865.

Grant wrote to the Army’s Adjutant General asking about arranging a transfer of the evidence to Ford’s, plus records of Lincoln’s short military service in the Black Hawk War. This was not the first time that a federal entity had requested permission to display the Lincoln assassination trial evidence, including weapons. In 1925, the Smithsonian Institution had made a similar request.

On June 29, 1931, the Adjutant General replied to Grant with the same answer he gave the Smithsonian: an unequivocal no. He outlined his reasoning in the letter I found in the NPS archives:

“The relics should not be displayed to the public under any circumstances, on the theory that they would create interest in the criminal aspects of the great tragedy, rather than the historical features thereof, and would have more of an appeal for the morbid or weak-minded than for students of history. […] the Lincoln relics should not be placed upon exhibition anywhere.”

That’s quite a statement.

What Changed?

At this point, you might be thinking, “Wait, I’ve seen the deringer in person at Ford’s Theatre and/or online. What happened between the time of the Adjutant General’s denial and today?”

Indeed, officials’ feelings about the weapon’s display did eventually change. In 1940, just nine years later, the War Department transferred the conspirator trial artifacts to the National Park Service (NPS), which had taken charge of Ford’s Theatre in 1933. Secretary of the Interior Harold Ickes announced that the trial artifacts would go on display on Lincoln’s birthday, February 12, 1940.

But a memo a few days later from Randle Truett, Lincoln Museum Superintendent, to the director of the National Park Service reflected caution. Truett noted that the Museum Division of NPS had divided the new artifacts into three categories: Impersonal, Personal and Borderline.

- Impersonal artifacts, like Booth’s keys, maps and compass, diary, photographs, and other weapons carried by the conspirators, were okay to display.

- Personal artifacts, like the pistol’s bullet from Lincoln’s brain and fragments of Lincoln’s skull, were considered inappropriate to display. (The National Park Service eventually transferred these to the National Museum of Health and Medicine, where they are held and displayed today.)

- Borderline artifacts included the deringer and the knife used in the simultaneous attack on Secretary of State William H. Seward.

Even though the weapon was originally advertised as part of that exhibit in 1940, at the last minute NPS managers decided to keep that item, along with the personal artifacts, in storage. The deringer was not displayed until the NPS created a special exhibition on the Lincoln conspiracy trial in 1942. That exhibition coincided with a World War II military tribunal—drawing on the Lincoln assassination trial as a precedent—of German saboteurs then taking place down the street at the Department of Justice.

Ford’s Theatre has continued to display the deringer since.

Should a Historic Site Display a Murder Weapon? 2020 Edition

As a site where political violence happened, Ford’s Theatre is a member site with the International Coalition of Sites of Conscience (ICSC). When putting together our site-wide interpretive plan in 2018, one of our discussions with ICSC and strategist Kate Haley Goldman involved the ethics of displaying the deringer. We fretted that the current display was too reverential—that it makes this murder weapon almost holy.

We talked about adding further interpretation to the display, like witness accounts from people who saw Lincoln assassinated, to provoke thought about the impact that weapon had. But we hadn’t gotten far beyond initial discussions. This letter showed that we weren’t the first to have those questions.

Thanks to the creative thinking of Director of Education and Interpretation Sarah Jencks, the rediscovered letter provided a new way to approach reinterpreting the deringer within the museum itself.

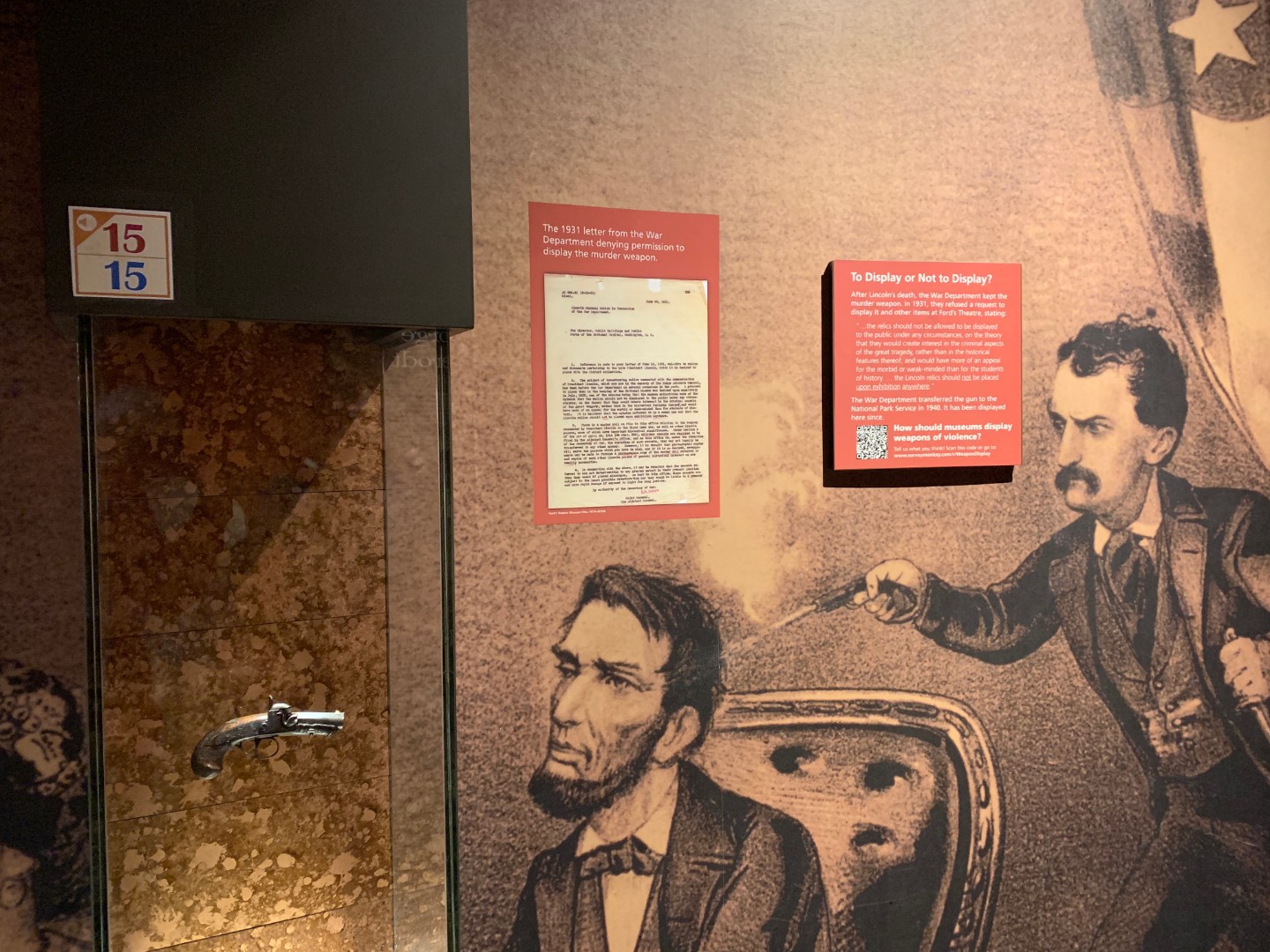

Just before our site closed for the COVID-19 pandemic, we installed two temporary signs by the deringer. One includes the complete text of the 1931 letter, and the other asks our visitors what they think about displaying the weapon. The second sign also includes a link to a survey where visitors can share their related opinions with us. We’ll share results of this survey in the future, as more visitors comment.

Thanks to Dr. Diane Putney, a retired Department of Defense historian, for sharing Ulysses S. Grant III’s letter to the Adjutant General with me. Thanks to Dave Byers, Supervisory Park Ranger at Ford’s Theatre National Historic Site, for piecing together the timeline of when the National Park Service first displayed the deringer. Thanks to Sarah Jencks, Glenn Klaus, Colleen Prior, Joanne Westbrook, Jeff Jones, Lauren Beyea, Jake Flack, Kristin Fox, Aly Baltrus and Paul R. Tetreault for working together on the new interpretive panel.