Solving the Unknown: What Astronomer Henrietta Swan Leavitt Accomplished

Copernicus, Galileo, Kepler, Herschel, Newton, Leavitt… Leavitt? Henrietta Swan Leavitt’s contribution to the field of astronomy is that she gave us the tools to map out the stars in the universe. She discovered the correlation between Period and Luminosity. This helped turn the sky into a three-dimensional map allowing astronomers to solve the unknown in the equation: Distance. A decade later in 1929, Edwin Hubble built off Leavitt’s work to demonstrate that the universe has more galaxies than just the Milky Way.

After completing her degree at Radcliffe in 1895, Leavitt’s passion for the stars led her to a position without pay at the Harvard College Observatory. Seven years later, she was then hired as a “computer” and began working for about 30 cents an hour in what was widely known as “Pickering’s Harem.” Dr. Edward Pickering, Director of the Harvard College Observatory, hired female computers to do “women’s work.” Women computers were considered too frail to operate the telescopes at night in cold temperatures. The women engaged in the painstaking task of studying and measuring photographic plates and comparing them to existing star charts to determine a star’s position and magnitude, or brightness.

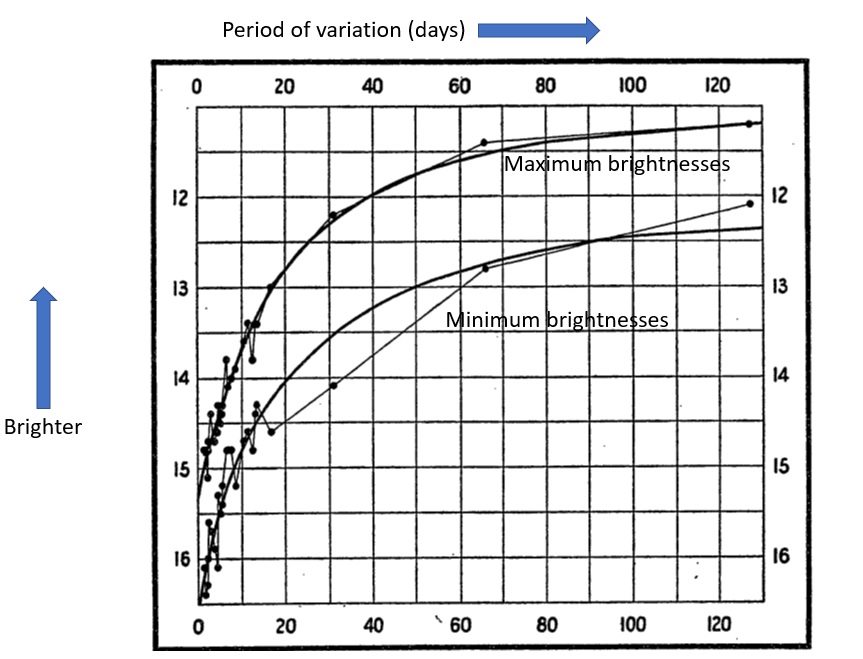

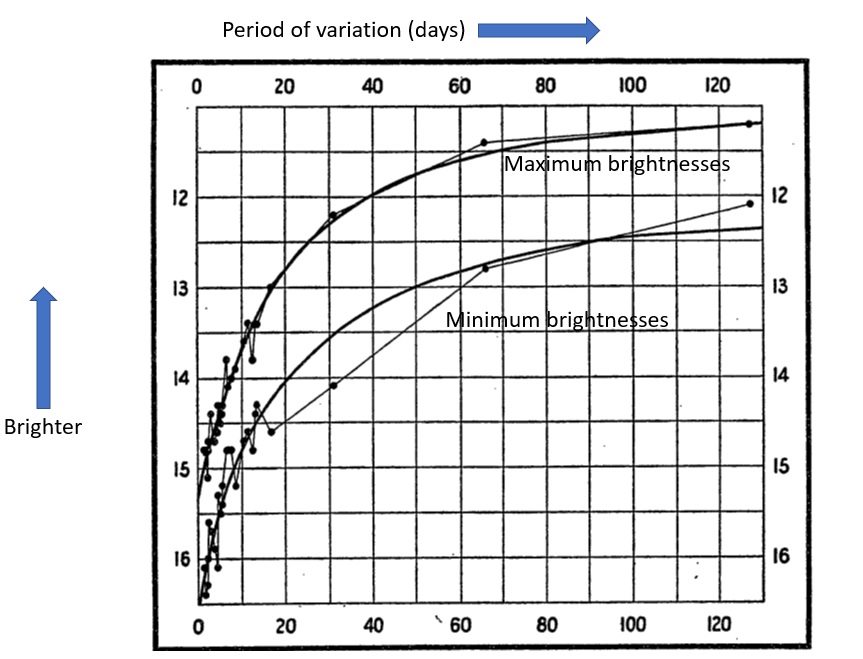

In 1908, Leavitt published her discovery of the period-luminosity relationship—that is, the correlation between how bright a star is and the time it takes for the star to go from bright to dim. Cepheid variable stars change how bright they appear from day to day or week to week as a result of their instability. Leavitt examined Cepheids in the Small and Large Magellanic Clouds and saw a clear pattern: the brighter variable stars appeared to go from their faintest to brightest, no matter how far away they were from Earth. Since these stars were all roughly the same distance away, and astronomers could measure their distance in the Magellanic Clouds, this meant that future astronomers were able to use the period-luminosity relationship to figure out the distance of places where these stars were found much farther away. The longer the star took to change brightness, the brighter the star.

It is worthy of notice that the brighter variables have the longer periods.

Henrietta Swan Leavitt

During her career, Leavitt catalogued more than 2,400 variable stars—about half of the known total in her day, without ever looking through a telescope. She catalogued alongside Williamina Fleming for the first part of her time at Harvard College Observatory and then with Annie Jump Cannon. In 1921, the new director of Harvard College Observatory, Harlow Shapley, appointed Leavitt Head of Stellar Photometry. She died later that year. In 1925, Swedish mathematician Gösta Mittag-Leffler nominated Leavitt for the Nobel Prize in Physics, not knowing that she had died four years prior.

Lauren Gunderson’s Silent Sky brings to life the story of Henrietta Swan Leavitt and the Harvard computers. These women deserve their rightful place in history. With this production, Ford’s Theatre celebrates their contributions and accomplishments.

Interested in citizen science? The Harvard College Observatory is transcribing and digitizing the notebooks of some of Harvard College Observatory’s most famous women computers, including Henrietta Leavitt and Annie Jump Cannon! If you’d like to contribute transcriptions for the Astronomical Photographic Plate Collection, you can help from your home computer by clicking here.

Olivia Wilson is former Artistic Programming Intern at Ford’s Theatre.