Suddenly Lincoln

Learn what Little Shop of Horrors can teach us about Abraham Lincoln.

We have all felt like Seymour Krelborn in Little Shop of Horrors at some point. The usually downtrodden Seymour has discovered a strange and interesting new plant after a solar eclipse. After his discovery seems to turn his fortunes around, this plant—which he names Audrey II in honor of his secret crush—begins to wilt and die. What follows is a classic musical number called “Grow For Me.” Just when it appears that Seymour’s life would change for the better, he is left begging this little sprout of hope to continue blessing him:

I’ve given you sunshine

I’ve given you dirt

You’ve given me nothin’

But heartache and hurt!

I’m beggin’ you sweetly

I’m down on my knees.

Oh, please –

Grow for me!

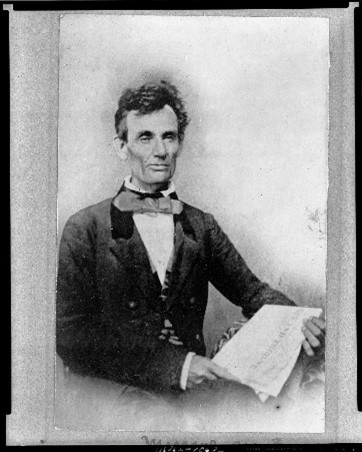

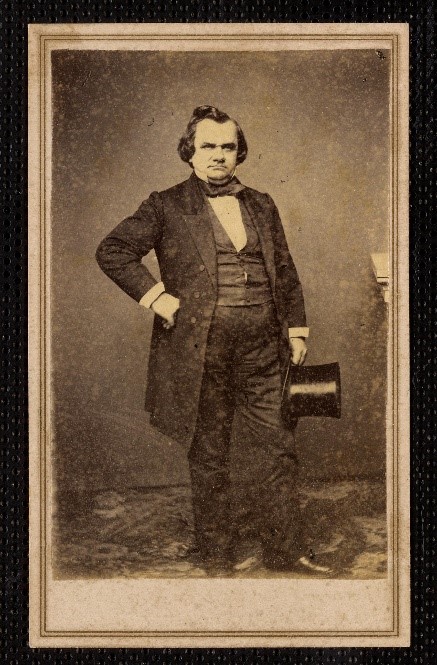

Before Abraham Lincoln—or anyone—knew this Illinois lawyer would be President of the United States, he ran two unsuccessful campaigns for the United States Senate in 1855 and 1858. As he lost both elections, the career of his longtime rival in Illinois state politics, Stephen Douglas, soared to newer heights in Congress. Douglas’s popularity and power was at its height in this period; politicos called him “the Little Giant” and people even predicted his ascendence to the White House.

As Lincoln’s prospects seem to go nowhere compared to Douglas, he wrote a private note to himself in 1856 that strikes a similar note as Seymour in “Grow For Me”:

“With me, the race of ambition has been a failure—a flat failure; with him [Stephen Douglas] it has been one of splendid success. His name fills the nation; and is not unknown, even, in foreign lands.”

Lincoln had given his political career sunshine, dirt and more, but it seemed in this moment that he would be doomed to always be second best, little more than a footnote compared to the perennial success of his world-renowned rival. It is a little heartbreaking to hear Lincoln call himself “a flat failure.” If only he knew!

Looking at the full scope of Lincoln’s life, however, this negative self-talk is not entirely surprising. Lincoln suffered with bouts of depression throughout his life. As a young man making his way in the world, Lincoln’s friends genuinely worried at times about his mental state. In a letter to a close friend in 1842, Lincoln even described his personal experiences with how “exposure to bad weather . . . [in] my experience clearly proves to be very severe on defective nerves.”1 His mother died when he was very young. He had a tumultuous relationship with his father. He lost two children to illness. Of course, he also navigated the country through the most challenging period in its history. Along the way, he led hundreds of thousands of men to sacrifice their lives to establish “a new birth of freedom,” a burden which Lincoln felt to his core.

This is not necessarily the Lincoln that we have grown up with. The face on the penny, the marble colossus and even the frontier tough rail-splitter are more familiar images. All are important national symbols, but there is something powerful in a human Lincoln, one that grappled with demons all too common in our society. Focusing too much on the mythic aspects of historical figures’ lives can create an unhealthy relationship between ourselves and our past. Specifically, hero worship can make us feel like we don’t measure up. How could we, when we build statues for them, whereas we are just . . . us, toiling away, hoping our own ambitions will grow like Seymour’s plant in Mushnik’s Skid Row Florists.

To aspire and live with purpose is to be human. Studies even show that living with a sense of purpose promotes good mental and physical health.2 But examining the fullness of Lincoln’s—or anyone else’s—experience teaches us to not let our ambitions get the best of us and to let disappointment pass. That examination also teaches us to take the time to study ourselves, to “live thoughtful and reflective lives” in the words of Lincoln scholar Ronald C. White.2

In the end, both Seymour and Lincoln experienced their own shares of success. Seymour finds romance and fame in Little Shop of Horrors, while Lincoln would go on to find a sense of purpose that has made him a legendary figure around the world. Even as he mourned himself as a “flat failure,” Lincoln also found comfort in dedicating that disappointment to something higher:

“I affect no contempt for the high eminence he [Douglas] has reached. So reached, that the oppressed of my species, might have shared with him in the elevation, I would rather stand on that eminence, than wear the richest crown that ever pressed a monarch’s brow.”

Finding success by elevating both ourselves and those around us is a healthy way to approach our ambitions. It is certainly healthier than feeding vampiric plants from outer space, and we see how Seymour’s selfish mindset – unlike Lincoln – has consequences. Come see Little Shop of Horrors at Ford’s Theatre and find out why!

Citations:

- Abraham Lincoln to Joshua Speed, January 1842, qtd. in Abraham Lincoln: Selected Speeches and Writings (New York: Library of America Paperback Classics, 1992), 30.

- Rosean Bishop, Ph.D., “Does purpose play a positive role in mental health?,” Mayo Clinic Health System, March 23, 2023. https://www.mayoclinichealthsystem.org/hometown-health/speaking-of-health/purpose-and-mental-health. Accessed March 14, 2024.

- Ronald C. White, Lincoln in Private: What His Personal Reflections Tell Us About Our Greatest President (New York: Random House, 2021), 163.

Little Shop of Horrors runs through May 18 at Ford’s Theatre. Get tickets here.

Blake Lindsey is the former Museum Interpretive Resources Specialist at Ford’s Theatre.