Washington’s Civil War Illuminations and a Modern-Day Win

On November 2, 2019, tens of thousands of people jammed the streets of downtown Washington to celebrate the Washington Nationals World Series victory. Cheering throngs of jubilant fans lined Independence Avenue to get a glimpse of the team that had ended the city’s 95-year baseball championship drought. There was a collective sense of joy, relief and celebration reverberating throughout the entire city. Our boys had finally brought home the title!

A similar sense of euphoria and relief engulfed Washington City following Confederate General Robert E. Lee’s surrender to United States General Ulysses S. Grant at Appomattox Court House on April 9, 1865. When Lee signed the surrender documents, the immediate threat to Washington was over. The Civil War officially ended just over a month later.

The mood this struck must have been similar to when sports fans watched Nationals’s second basemen, Howie Kendrick, hit a two-run homer in the seventh inning of Game 7 of the World Series to put the Nationals ahead for good. The game wasn’t officially over, but victory was soon to come. It was time to party.

According to an April 11, 1865, article in the Evening Star, on April 10, the day after the surrender, Mayor Richard Wallach and the City Council unanimously adopted a resolution stating:

“That in view of the surrender of General Lee and his whole army to Lieutenant General Grant, and the assurance which it gives of a speedy restoration of the Union, the citizens of Washington are hereby earnestly requested to manifest their rejoicing in the this glorious event by illuminating their private residences, places of business, and all the public buildings on Thursday night, the 13th instant, beginning at 8 o’clock” [sic].

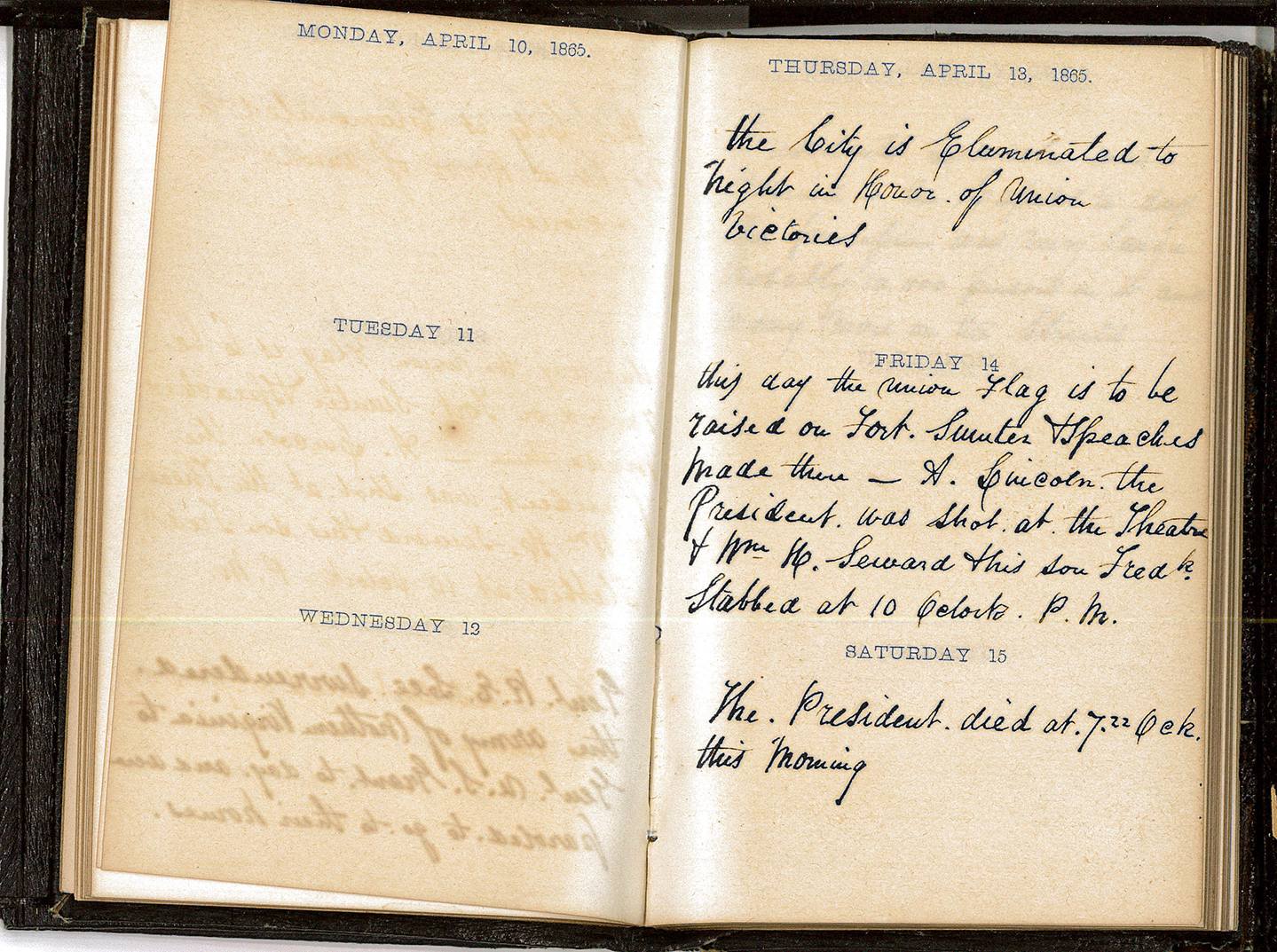

And illuminate they did. An article in the April 14 Evening Star describes the previous night’s display:

“Last night Washington was ablaze with glory. The very heavens seemed to have come down, and the stars twinkled in a sort of faded way, as if the solar system was out of order. Everybody illuminated.”

The article goes on to describe a sea of people streaming towards Pennsylvania Avenue as the sun went down. All 195 widows of the Post Office were lit with 3,500 candles and the 230 windows of the Patent Office (today the National Portrait Gallery & Smithsonian Museum of American Art) were ablaze with 5,000 candles. In front of the Willard hotel gas jets spelled out the word, “Union”. Most every restaurant, hotel, government building and private residence in downtown Washington was illuminated in celebration.

The very next day the flames of joy would be extinguished by the tragic news of the assassination of President Lincoln at Ford’s Theatre. Black mourning cloth quickly replaced the candles and torches in windows all over the city. The unbridled sense of joy and relief turned to anger, grief and uncertainty.

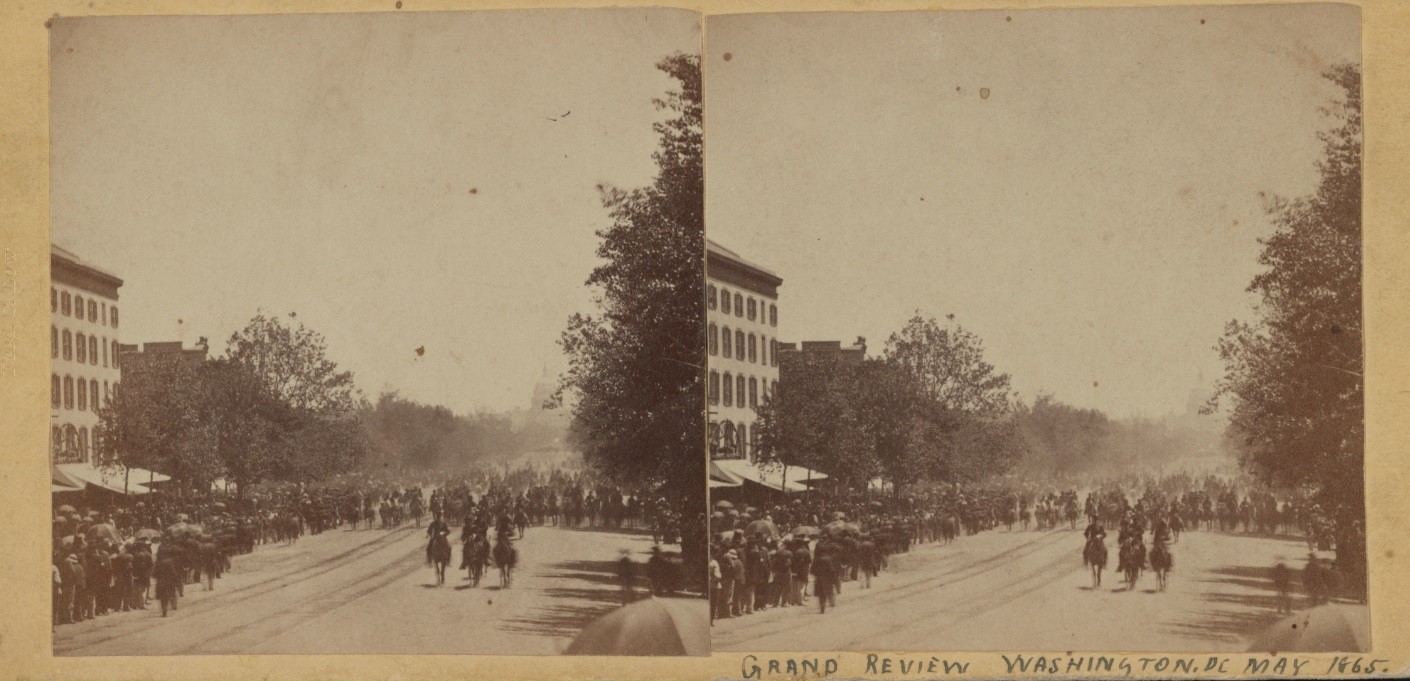

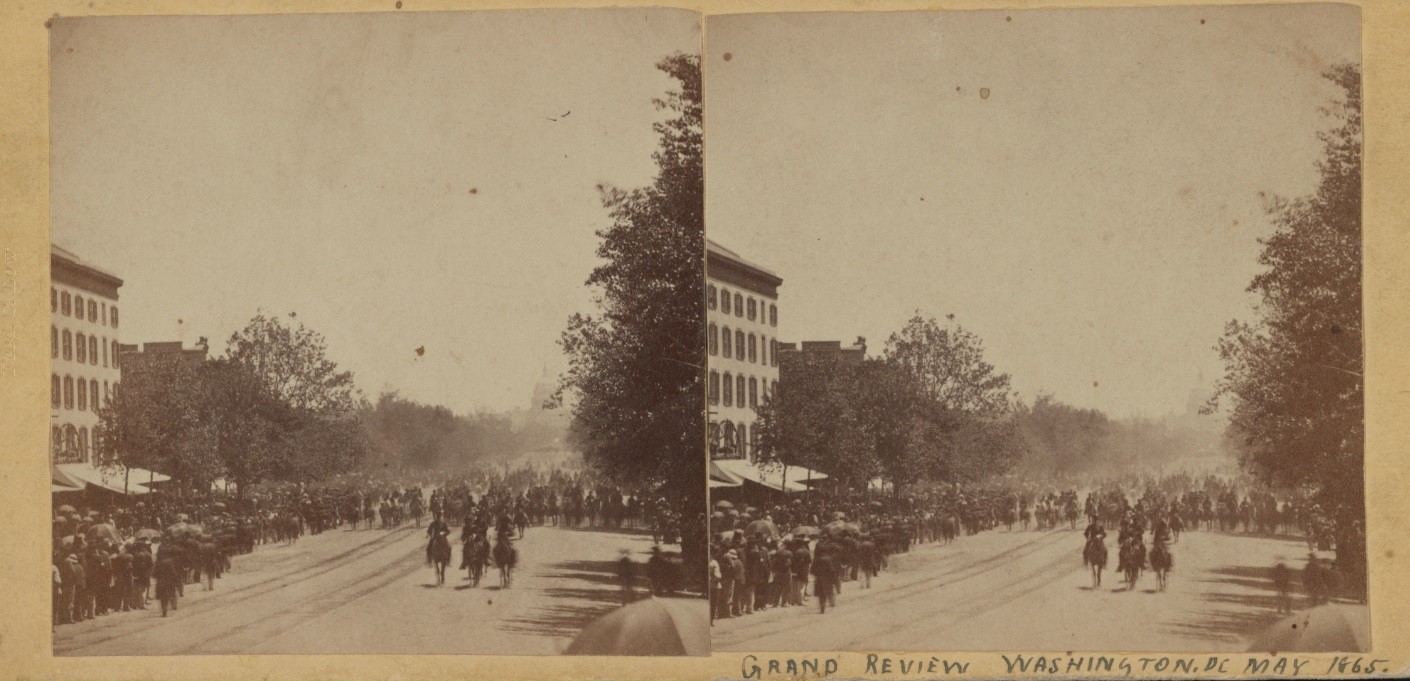

Five weeks later, the dark mood in the capital city was lifted by the sight of waves of victorious United States soldiers marching down Pennsylvania Avenue. This massive parade, known as The Grand Review of the Armies, featured an estimated 145,000 soldiers during May 23 and 24, 1865. Once again, thousands of people lined America’s main street, Pennsylvania Avenue, to share in a collective mood – this time pride and joy. Our boys had finished the fight.

Jake Flack is Associate Director of Museum Education and a rabid fan of the Washington Nationals.