Which Knife Did John Wilkes Booth Use? Disentangling the Lincoln Assassination Knives

Recently, Lincoln assassination researcher Dave Taylor raised questions about whether a knife in the Ford’s Theatre Museum was really the knife that John Wilkes Booth used to stab Major Henry Rathbone while in the Presidential Box on the night of April 14, 1865, as the label currently indicates. Taylor argues that another knife—with object number FOTH 3218, also called the Rio Grande knife—was the knife that Booth used, rather than the currently displayed knife, object number FOTH 3235, also called the Liberty knife.

Following Taylor’s post, we—NPS curator Janet Folkerts and FTS Associate Director for Interpretive Resources David McKenzie—looked through on-site curatorial records to investigate further and see if we could come to a conclusion. We focused on three types of records: catalog files, accession files and photographs.

Catalog Records

We first looked at the catalog records for the relevant items. A catalog record is, essentially, the descriptive information about each item in a museum’s collection—its physical characteristics, its backstory, etc. This would help us see how past collections managers understood each of these items.

The catalog file for FOTH 3218 (the Rio Grande knife) mostly contains descriptions of its physical characteristics. However, an insurance list from 1997 contains an intriguing clue: It identifies FOTH 3218 as the knife “used by Booth to Stab Major Rathbone.” Sadly, it provides no other evidence.

The catalog record for FOTH 3235 (the Liberty knife) has a bit more information in it. A 1965 catalog card says that it was “one of the items used as evidence in the trial of Lincoln’s Conspirators,” but does not identify it as Booth’s. No other documentation in that file makes an identification one way or the other.

Accession Files

When a museum brings an artifact into its collection and commits to caring for it, it accessions that item. In 1940, the office of the U.S. Army Judge Advocate General transferred its collection of Lincoln assassination evidence, including the two knives, to the National Park Service, specifically to the Lincoln Museum. The file about this accession, number 190, contains more clues.

In the file, a 1940 press release announcing the display of the items refers to the knife Booth used to attack Rathbone. A handwritten note to the side—with no date but appearing to correspond to other notes either written in 1960 or 1988—identifies that item as FOTH 3218 (the Rio Grande knife).

A copy of an undated and unidentified newspaper clipping, though, identifies the knife Booth used to wound Rathbone as saying “AMERICA-Liberty and Independence.” This is the knife that later became FOTH 3235 (the Liberty knife).

A photo in the Washington Star in 1908, which Taylor reproduces in his post and is also in the Accession 190 file, shows three knives, labeled 6, 16 and 21. Knife 6 is identified in an accompanying article as the one that Booth used on Rathbone. Unfortunately, the photo—printed using early-20th-century technology—is too fuzzy to distinguish which is which (although this knife appears to have a straight blade, like FOTH 3235—the Liberty knife and unlike FOTH 3218, the Rio Grande knife). Since the files of the original Washington Star photos at the D.C. Public Library go back to only 1935, this is, sadly, likely the best view available to us.

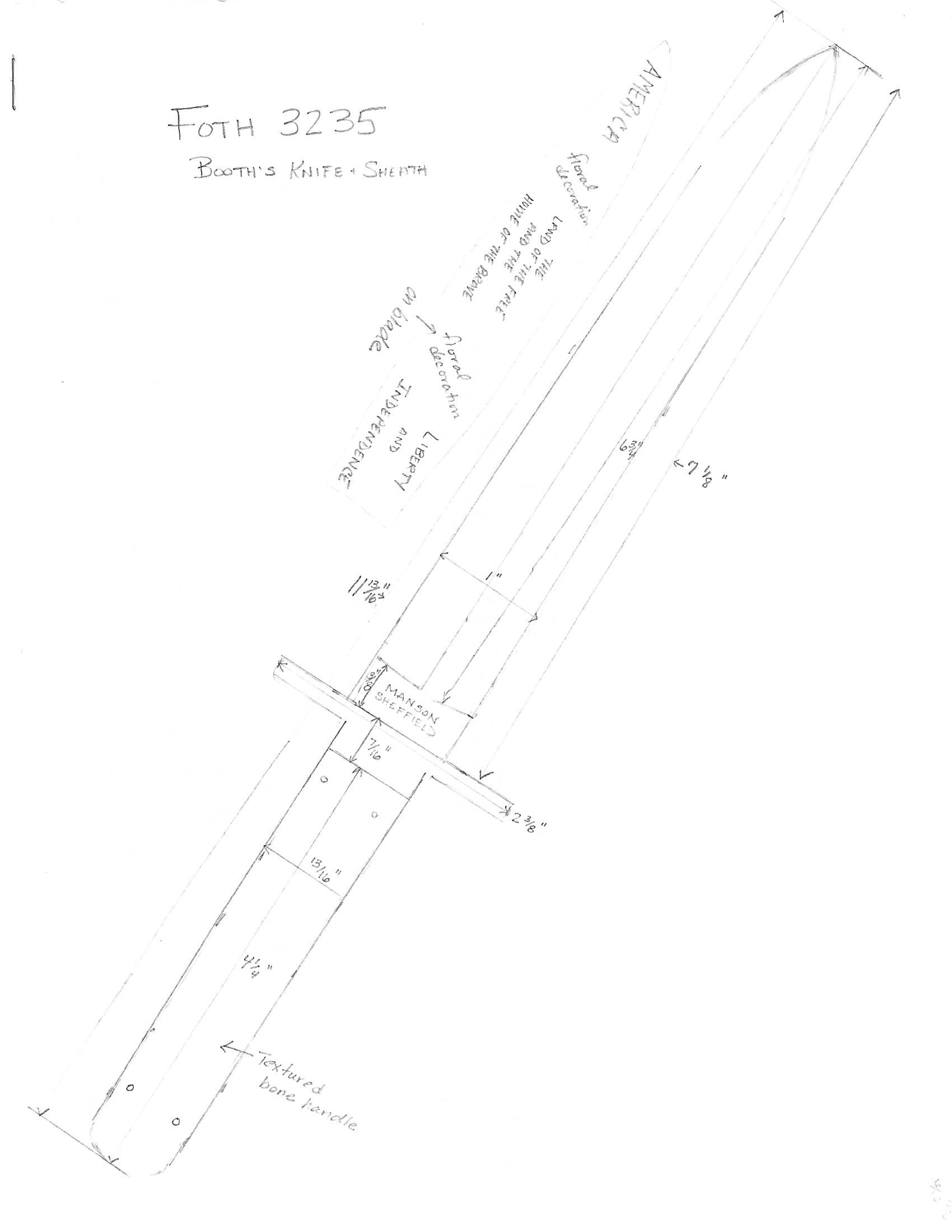

In the same file, an undated sketch of FOTH 3235 (the Liberty knife) identifies it as “Booth’s knife.”

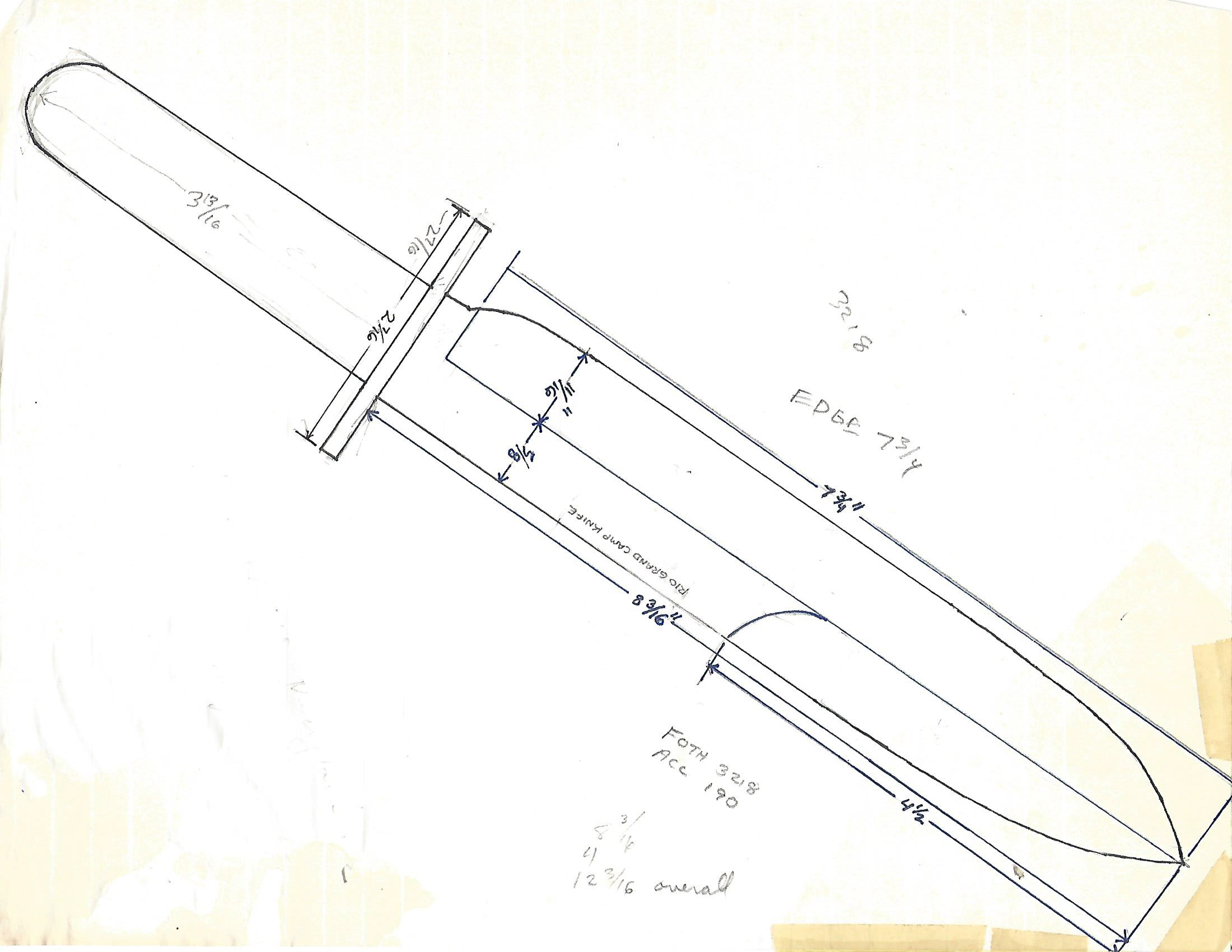

An undated sketch of FOTH 3218 (the Rio Grande knife), which appears to be in the same hand as the one above, does not have a label.

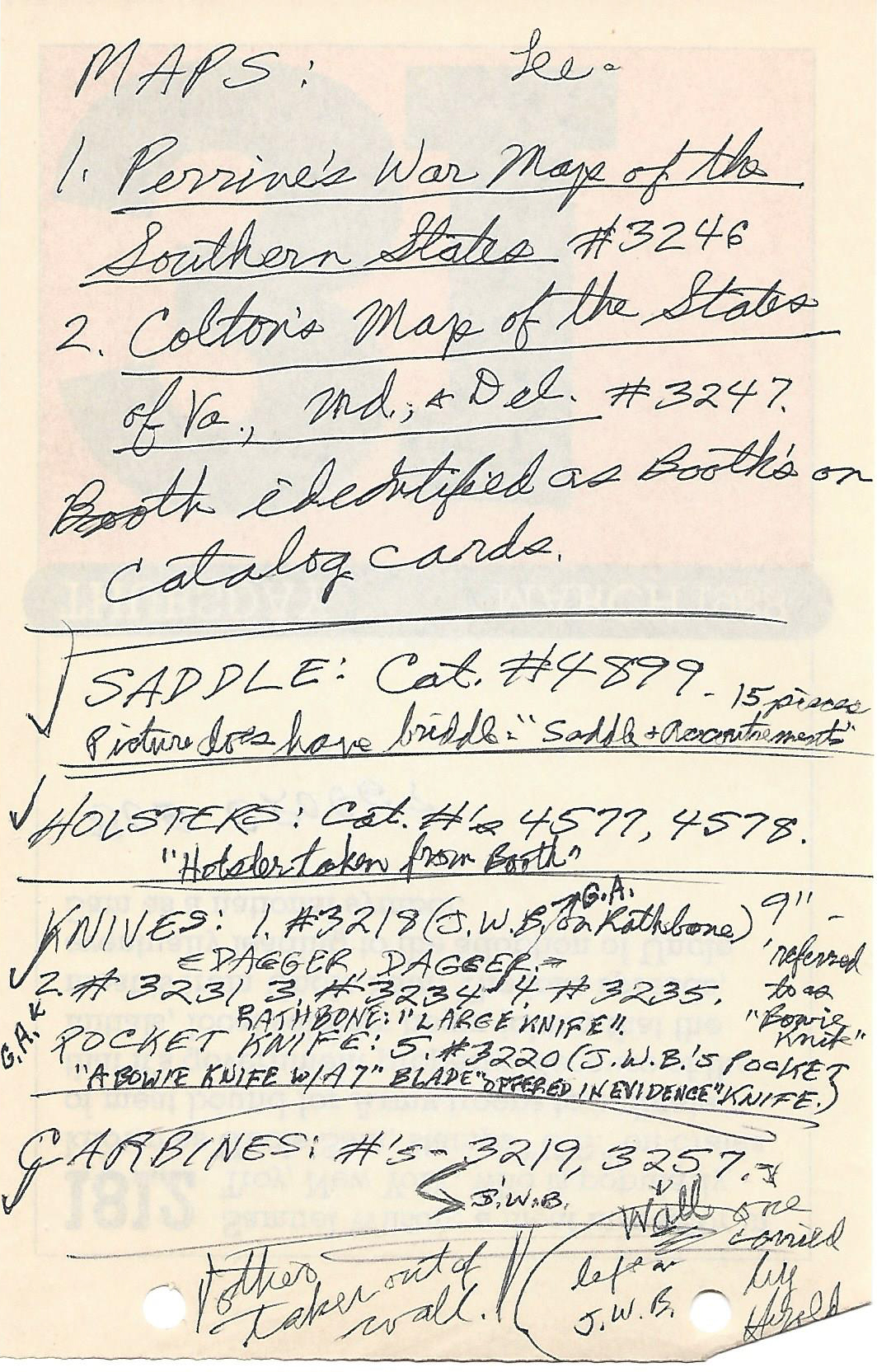

Another, also undated, list of items from that accession notes “#3218 [the Rio Grande knife] (J.W.B. on Rathbone),” but provides no other clues.

So, different documents in the accession file identify each knife as the knife that John Wilkes Booth used to stab Major Rathbone, but they don’t provide evidence for their assertions—or even dates on which they were written.

Exhibition Photographs

In his post, Taylor refers to books showing photos of FOTH 3218 (the Rio Grande knife) on display—and identified as Booth’s knife—at the Lincoln Museum at Ford’s Theatre during the 1950s and 1960s (before the theatre was restored to its 1865 appearance between 1965 and 1968). So, after looking at the catalog and accession files, we looked at photos of displays in the museum. Frustratingly, among the dozens of photos of displays at the Lincoln Museum, we didn’t see any photos of either knife.

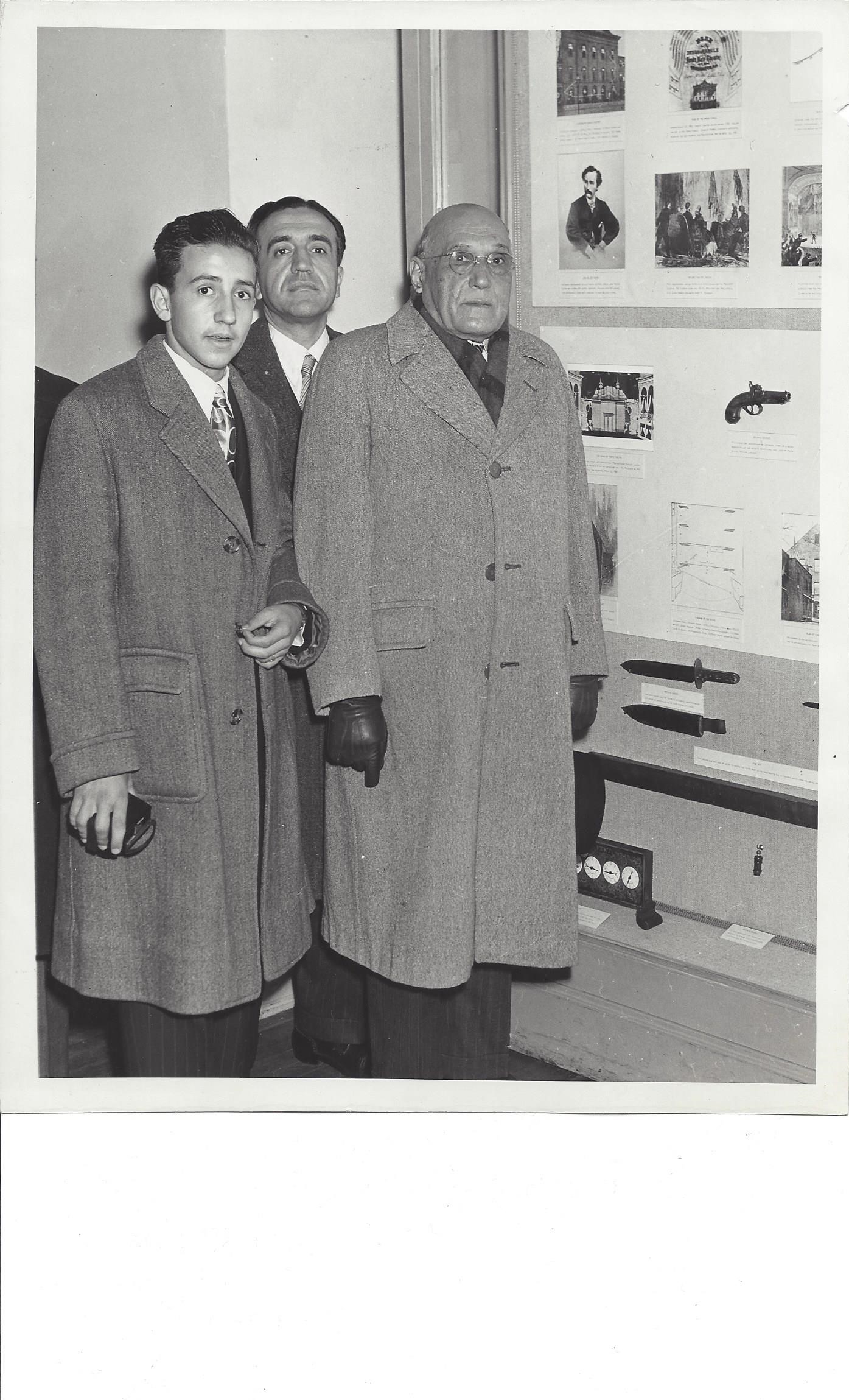

But then, as often happens when researching, serendipity struck when we looked at a folder labeled “President-elect of Uruguay’s visit, 1947.” One photo shows the President-Elect, Tomás Berreta, and two other men standing in front of a display case of photographs and artifacts about the assassination—including a knife. Zooming in closely on the image, we see that this appears to be FOTH 3218 (the Rio Grande knife), and is labeled as “Booth’s knife.” So, indeed, at this point, FOTH 3218, rather than FOTH 3235 (the Liberty knife), was considered to be Booth’s knife.

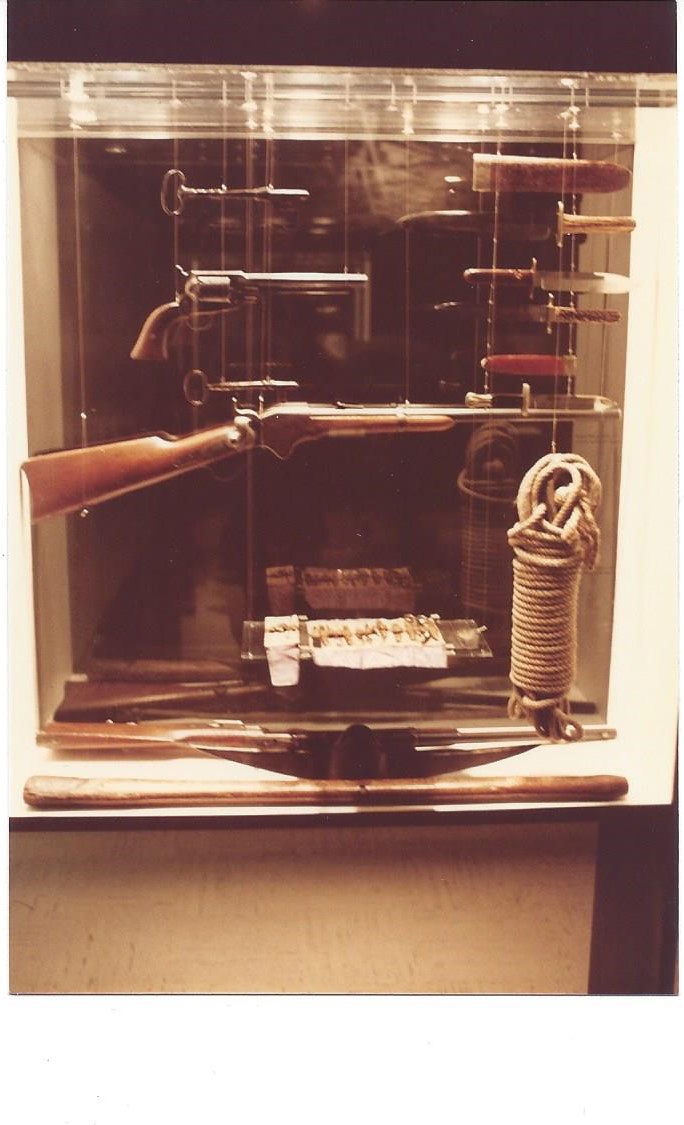

A photo of a display from 1981 shows the knives but no identification labels.

A Conclusion? Not Quite.

So what do we make of this conflicting evidence?

In his post, Taylor presents additional evidence that the knife currently on display at the Ford’s Theatre Museum, FOTH 3235 (the Liberty knife), is not the actual knife. He cites testimony of witnesses in the assassination investigation, the 1865 military tribunal and the 1867 trial of John Surratt to argue that FOTH 3218 (the Rio Grande knife) is the knife that Booth used to stab Rathbone, and not FOTH 3235 (the Liberty knife), the knife that is currently on display at the Ford’s Theatre Museum.

Between that evidence and what is in the curatorial files described above, we’re inclined to say, at the very least, that a good amount of evidence points to that conclusion. But because the evidence is so messy, as Taylor notes, we aren’t prepared to make a definitive declaration.

We are prepared, though, to say that future on-site and online labels at Ford’s Theatre will reflect the ambiguity of the knives, rather than make a definite declaration. Our journey through the curatorial records shows how even the most important historical items can sometimes lose evidence of their provenance over the years, due to mislabeled or incomplete notes, incorrect identifications, inventories with very little description, constant handling or movement, or hurried work. Perhaps a future display could, like Taylor’s post and ours suggest, showcase both knives and lay out evidence to show our visitors how ambiguous historical evidence often is.

Knowing exactly which knife was used doesn’t change our knowledge of the events of that night, nor of their long-term consequences, but transparency about artifacts like these knives can lead to discussions about what makes visitor experiences in museums “real” and how the history of objects and places affect us in the present day.

Janet Folkerts was acting Museum Curator for the National Park Service, National Mall and Memorial Parks.

David McKenzie was Associate Director of Interpretive Resources at Ford’s Theatre Society. He works to create resources to help people today learn from the people, places, and things of the past. Prior to coming to Ford’s in 2013, he worked in a broad-ranging interpretive job at the Jewish Historical Society of Greater Washington, as a content developer at the exhibition firm Design Minds, and began his career as a front-line history interpreter at the Alamo.